The price of hedging China risk on world markets hasn’t fluttered during the past couple of weeks, which means that investors with real money on the line and speculators looking for a score aren’t worried about China’s property market.

Credit default swaps are a form of bond insurance that makes creditors whole after a default. They are quoted in basis points (100ths of a percent) above the cost of interbank funding. The cost of default protection on China traded Aug. 18 at 80 basis points, on the lower side of its historic range.

Even in an extreme case, I showed in a companion article, China’s central government could cover the interest payments on defaulted local government debt with a bit over 1% of tax revenues. The shakeout in the property market and the financial vehicles that lend to it, including Local Government Financing Vehicles, isn’t a financial crisis as such; rather, Beijing is asserting central control over local governments that have coasted for years on rising land prices.

The broad Chinese corporate bond market has ignored the property market fallout.

There’s a world of difference between the performance of property bonds, which make up most of Bloomberg’s China High Yield US Dollar Index, and the performance of investment-grade Chinese corporate bonds. The chart above shows that the high-yield dollar bond index has lost more than three-quarters of its value since the middle of 2021.

But the overall China bond index has registered positive returns throughout, and Bloomberg’s index of lower investment grade Chinese corporate bonds (rated Baa by Moody’s) has gained as well. The US corporate bond market has fallen in value because the Federal Reserve pushed up US interest rates. Bond prices move inversely to yields.

China’s RMB (ticker CNH) is lower against the US dollar, but that’s due to higher US dollar interest rates, not RMB weakness. The Chinese currency has traded in lockstep with the Japanese yen for the past year.

In regression analysis, US “real” yields (the yield on 5-Year Treasury Inflation Protected Securities) and Chinese government bond yields explain 80% of the movement in the Chinese currency, as shown in the chart above.

The cost of hedging the Chinese RMB against the US dollar, measured in points of option-implied volatility, is in the middle of the range that has prevailed since 2015.

The volatility of short-term interest rates in China meanwhile is close to the bottom of its long-term range. During real periods of stress, such as the Great Financial Crisis or the Covid recession of 2020, rate volatility jumped in China. It hasn’t moved in the past month.

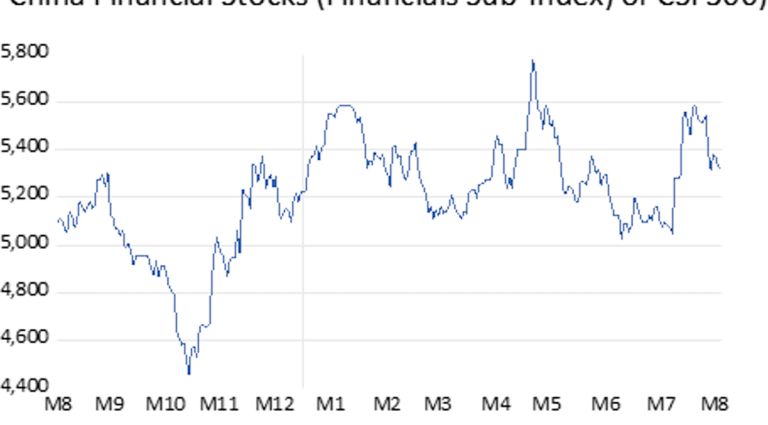

Chinese financial stocks are still up over the past year, which we would not expect to see if the financial system were at risk.

The simple fact is that countries with enormous trade surpluses and very high savings rates don’t have financial crises. The Chinese government has the resources to cover the debt service of dodgy local government debt if it so chooses, and the banking system has vast resources to issue new loans. Whether Beijing will do so is a political, not a financial choice.