Researchers have also found mentions of Qalah – the Arabic word for ancient Kedah – inscribed on documents used in Mesopotamia in 1300 BC, much older than his 788 BC discovery, Mokhtar said.

“It shows there is contact with Mesopotamia – the earliest civilisation in the world 8,000 years ago. But we have not found evidence yet. So, it is very important that future research gets this data.”

Mokhtar hopes the next generation of archaeologists can “complete” his data to determine how big and old Bujang Valley actually is, stressing that it is part of Malaysia’s natural heritage, identity and pride.

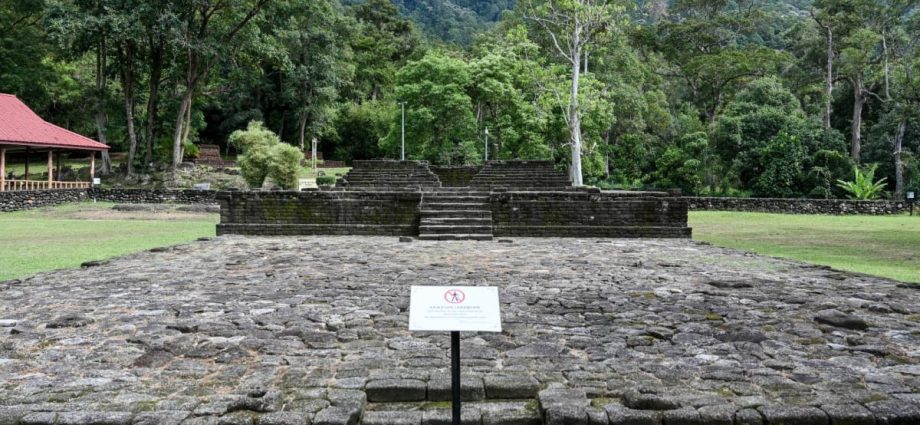

“The government should look at Bujang Valley as what Rome did for Pompeii,” he said.

“Also because archaeotourism brings a lot of income, like Borobudur and Angkor. You must look at Bujang Valley at that level.”

SEARCHING FOR A SUCCESSOR

But Mokthar said no one has taken over him yet to lead a team that will continue researching the Bujang Valley complex, and that he does not know the reason why.

While some of his former students are currently working at the site as part of their curriculum, he stressed that it is not easy to do this full time.

“The work is tough; you are both the worker and boss,” he said, adding that archaeology involves manual labour and interpretation in a tedious and time-consuming documentation process.

“When I retired, I did not expect that nobody would continue (my work). If someone continued, I could help out.”

CNA has asked Malaysia’s National Heritage Department, which manages the Sungai Batu site, for an update on the project.