Financial markets are flashing a range of danger signals about the path Washington and the Fed are on now. They reflect the weakened ability of the Fed to fight inflation, as the present confrontational talks about the federal government’s budget add to compounding mistaken policies since 2008.

The 10-Year Treasury is at 3.4% where it was in 2011; Gold price hovers above $2000 as it did in 2011 – another year when tense negotiations about the budget were looming. Both the rate and gold price have increased rapidly since June 2022.

The 5-year credit default swap was at 14 basis points a year ago and is now (as of April 12) at 35.25, meaning that the cost of insuring a $10,000 Treasury went from $14 to $35.25. The latter figure reflects a 0.59% implied probability of default on the assumption of 40% recovery rate. The one-year CDS jumped in January from 17 to 80 basis points – the latter being the same level as in 2011, when, as noted, there were likewise stressed negotiations about the budget. The rates in recent T-Bill auctions went from 4.5% in November to between 4.65 and 4.9%.

Even if the jump in the 1-year CDS signals a small chance of default related to the budget negotiations, and the 5-year CDS still signals a small chance of the US government defaulting on the debt, the above numbers mean that investors now request insurance against the Treasury’s default.

These numbers remind us of the following, too: President Obama’s 2011 budget was $3.83 trillion, its priorities the same as now: jobs, health care, clean energy, education, and infrastructure. The federal deficit that was forecast was $1.27 trillion in 2011 with debt to increase to $15.1 trillion – the tight negotiations having led to only a minuscule 1 percent reduction in spending.

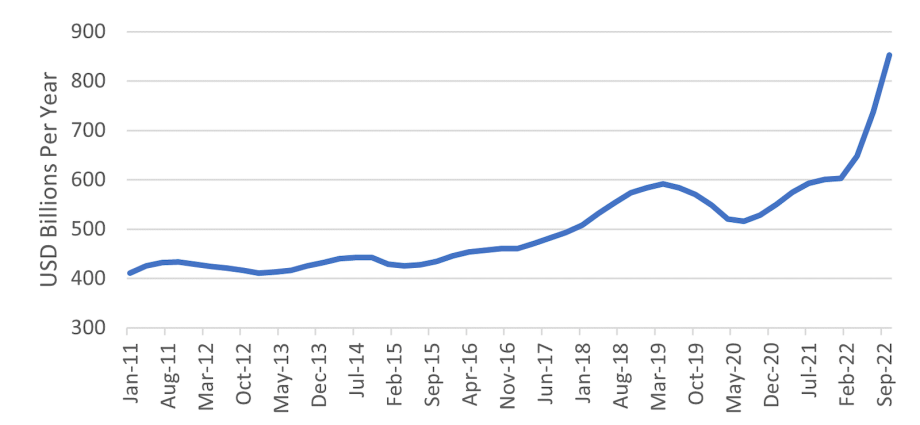

National debt doubled to $31 trillion and government spending doubled, too, to almost $7 trillion, but the US GDP went up only 50% from $15 to $23 trillion.

Last, but not least, the Fed remitted to the Treasury about $1 trillion over the last decade. It stopped remittances in September 2022 as its expenses exceeded its income by $20 billion. This loss reflects the higher interest on the debt the Fed bought for more than a decade as the Treasury issued long-term debt and the Fed issued short-term debt.

Depending on future interest rates, the Fed’s net income could remain negative for years; remittances cease and the negative amounts compound under a “deferred asset” category that the Fed created after passing a January 2011 rule to allow it. The rule lets the Fed count only interest income when sending remittances to the Treasury and ignore mark-to-market values as the Fed may hold the securities to maturity. If the Fed sold them before, it would have to recognize its MTM losses and the country face a disastrous fiscal event, as the numbers below show – and the danger signals reflect.

The Fed has $6.2 trillion in interest-paying liabilities that include $3 trillion of reserves and $2.5 trillion in reverse repos. A jump to 7% interest with persisting inflationary expectations would mean a roughly $420 billion interest expense by the Treasury to the Fed, and the Treasury having to roll over its loans at this rate. As of now, the interest rate the Fed pays on bank reserves and reverse repos is about 4%, and credit default swaps prices discount heavily such major jumps in rates that could result in either severe cuts in government spending or defaults.

The flashing danger signs reflect an additional problem. Unprecedentedly, the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 let the Fed pay the Fed’s fund rate on the banks’ excess reserves. Assisting banks during crises draws on Bagehot’s Lombard Street principle: When the financial sector goes through dramatic liquidity and solvency crises, central banks must step in. However, the principle requires not helping insolvent banks at all, but lending to solvent banks – but charging them higher rates.

The inadvertent impact of the misguided 2008 act was that banks expanded uninsured demandable deposits. The banks deposited them at the now returns-paying-on-excess-reserves Fed, expanding both the Fed’s and the banking sector’s balance sheets. Because these deposits can promptly flee – as the SVB case showed – the banking sector became weaker, more unstable.

Thus, Washington and the Fed operate now under the constraints of weakened wealth creation since 2011, a weakened banking sector and a more radical political division than in 2011 in matters of government spending in particular. The danger signals suggest that the present path Washington and the Fed are on – trying to remedy both the 2008 crisis and the two-years-war-like-Covid-shutdown – increased the chances of bringing the US to the edge of the precipice.

The path of higher taxes and an increasing burden of regulations is not the solution, as they diminish incentives to invest (though governments may categorize spending as “investment”) and decrease the demand for credit and liquidity. The Fed must absorb the unwanted credit and liquidity it created to prevent a jump in inflation, but it is now severely limited in its ability to do so.

The solution would be to reduce government spending and regulatory burdens to relieve the pressure on the Fed and on financial markets as well as dependence on foreign capital. The flashing danger signals show that this is not the path taken and they are a reminder of Paul Volcker’s observation that politicians and bureaucracies “respond best to nice bright red and green signals: trying to flash subtle shades in between is almost as hard as squaring a circle.”

Still, danger signs notwithstanding, while all major currencies dropped significantly relative to gold in the last 10 years, the Swiss Franc and the US dollar were the best fiat performers by far at roughly a 45% drop. In the planet of the blind, the present one-eyed US and its currency, the dollar remain kings.

The article draws on Reuven Brenner’s The Force of Finance: Triumph of the Capital Markets (2002), and a series of analyses on the 2008 Crash and monetary affairs in American Affairs and The International Economy.