SINGAPORE – Robust demand for Singapore’s electronics and semiconductors during the pandemic fueled the city-state’s fastest economic expansion in over a decade and big-ticket investments in chip-making capacity.

Now, the notoriously cyclical semiconductor industry is in the grip of a deepening downturn as geopolitical and inflationary headwinds buffet the global economy.

Chip makers in the island nation are increasingly concerned about the near-term possibility of a recession, with many feeling the sting of soaring electricity prices linked to energy market disruptions worsened by Russia’s war on Ukraine.

Singapore-based semiconductor and related firms are also contending with a tight domestic labor market and new regulations that have raised the cost of and otherwise discouraged hiring foreigners.

“What is happening with Ukraine, with the shutdowns in China…when the uncertainty of a possible recession is coming up, or even stagflation in some countries, there is a fear that consumer demand will start to drop. Of course, this will have a direct impact on chip demand,” said Ang Wee Seng, executive director of the Singapore Semiconductor Industry Association (SSIA).

Faltering global demand is already being acutely felt in Singapore, with manufacturing sector growth falling to an 11-month low in August. All sector segments saw a fall in output, led by a 19.3% slide in the production of modules and components. It marked the third straight month of contraction in semiconductor production; the broad electronics sector has shrunk for two consecutive months.

Singapore’s domestic non-oil exports continued to grow in August despite a decelerating global economy, driven mainly by shipments of non-electronic products. But electronic shipments declined by 4.5% month on month in August, shrinking for the first time in almost two years. The sector’s Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) fell to 49.6, down 0.9 points from July, with a reading below 50 indicating a contraction.

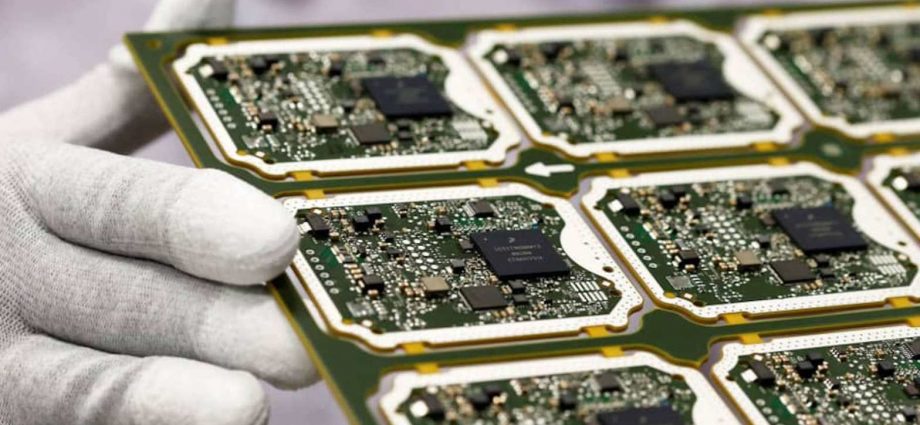

Though better known as a financial and trade hub, Singapore accounts for about 11% of the world’s semiconductor exports and the manufacture of around one-fifth of global semiconductor-making equipment. Large chip multinationals including GlobalFoundries, Siltronic and United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC) all have expanding footprints in the city-state.

Apart from drawing global players, Singapore boasts an ecosystem of small and mid-sized firms that have for decades climbed the value chain to offer high-end services such as wafer fabrication and semiconductor capital equipment manufacturing.

The island nation still lags behind Asia’s biggest chipmaking powerhouses but is rapidly emerging as Southeast Asia’s most important semiconductor manufacturing base, particularly as many seek to reduce their reliance on Taiwan, which makes 65% of the world’s semiconductors and almost 90% of the advanced chips, amid rising tensions with China.

“One challenge the industry is facing and will continue to face is the deteriorating relationship between [the] United States and China, and this is definitely disrupting our industry’s supply chain both short and long term,” said SSIA’s Ang, alluding to US efforts to curtail Chinese semiconductor advancements in an escalating tech rivalry between the world’s two largest economies.

Industry experts see a rising opportunity for Singapore to expand its share of the semiconductor market as part of a global supply chain that, apart from Taiwan, is currently concentrated in the United States, South Korea, Japan and China. That prospect has many optimistic about the local chip sector’s long-term outlook despite darkening short-term expectations for the industry.

“The sharp decline in electronics exports raises the risk of a technical recession (in the third quarter),” said Maybank Kim Eng Research economists Chua Hak Bin and Lee Ju Ye, who expect Singapore’s non-oil domestic exports “to ease and even turn negative in the coming months” in the face of rising global interest rates and inflation.

Sagging demand for Singapore’s chips and other electronics mirrors the prevailing trend in global chip sales, which have decelerated for seven straight months, according to the Washington-based Semiconductor Industry Association. That marks a sharps reversal of the pandemic-era surge in demand for chip-powered personal tech and computing goods that stretched and in places broke supply chains as factories closed amid lockdowns.

Widespread component shortages spurred many large multinational chip makers to make major new investments in capacity, including in Singapore where several companies have committed billions of dollars to build new plants. That is partly why, even amid a manufacturing downturn, observers do not anticipate much let-up in the ongoing talent crunch facing the industry.

As of last year, Singapore’s semiconductor industry employed more than 33,000 people with at least another 2,000 jobs slated to be created in the next three to five years. That figure could be even higher if the world’s biggest contract chipmaker, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), moves ahead with plans to open a multi-billion-dollar factory in the city-state.

In May, the Wall Street Journal reported that negotiations were underway between the Taiwanese chip-making titan and the government’s Economic Development Board, which is considering whether to help fund the construction of a plant that would make seven- to 28-nanometer chips. Citing anonymous sources, the report said a final decision on the project had not yet been made.

Singapore’s chip sector relies on a relatively small pool of high-skilled workers in areas such as wafer fabrication, assembly and testing. Authorities in the city-state have promoted education and training to attract local recruits to the chip workforce, but many companies remain dependent on overseas labor, which became scarce during earlier quarantine clampdowns.

Stiff competition for talent continues to hound chip makers along with tightness in Singapore’s labor market despite the broader easing of Covid-19 restrictions. Rising unemployment during the pandemic drove the government to raise the salary threshold criteria for hiring foreign workers in a bid to incentivize local hires, which has put a squeeze on companies that rely on foreign talent.

“Talent acquisition is tough, especially if we are talking about unique skill sets. There are certain skill sets that are not available in Singapore, so we have to import them,” said Valerie Lee, head of human resources at ams OSRAM, an Austria-based firm that designs and produces optical and integrated modules for sensor and light technologies.

“In manufacturing, we are very dependent on machine operators who are not local. You can’t get a local to do an operator’s job. No one is interested,” lamented Lee, who told Asia Times that ams OSRAM operates two advanced assembly manufacturing facilities in the city-state with around 3,500 employees.

Singapore’s ratio of job vacancies to those unemployed reportedly reached a historic high in the second quarter. In late August, the government announced new visa rules to attract top-tier global talent, allowing foreigners earning a monthly minimum of S$30,000 (US$21,431) to secure five-year work passes, with some exceptions for outstanding candidates that fall short of salary criteria.

The measure certainly isn’t expected to ease broader job market tightness as few professions outside of banking, finance and legal services meet the salary threshold. Meanwhile, the monthly salary criteria for an Employment Pass, a work permit for middle-class foreign professionals, was this month raised to S$5,000 ($3,483) up from S$3,900 ($2,717) in 2020, forcing many businesses to increase their operating costs.

Jason Ling, managing director of LED and lighting component maker Lumileds, said the company’s talent acquisition efforts were “definitely impacted” by pandemic travel restrictions, and policy changes since have necessitated it to “adjust our talent requirements to better suit the local talent pool in Singapore in support of the government strategy to upskill the local workforce.”

Others are treading carefully in the labor market amid signs of a sectoral downturn. “We’ve increased the headcount throughout the year. Now, I wouldn’t say we are putting our brakes on, but I can tell you our management is taking a more of a cautious approach,” Asif Chowdhury, senior vice president of marketing and corporate business development at UTAC Group, a Singapore-owned semiconductor assembly and test (OSAT) vendor.

Energy price hikes are another factor weighing on businesses in industrial-related sectors. Singapore’s electricity inflation rate hit a record 24% in July, capping off an extended period of energy market turmoil and price volatility linked to supply and demand factors that have been exacerbated by Russia’s war on Ukraine.

“In terms of the material shortages from Ukraine, we have not seen a direct impact on the industry yet,” said SSIA’s Ang. “But the one thing that has hit us badly are energy prices, which have been skyrocketing since late last year. That has a direct impact on the operating costs for companies here and may even impact potential upcoming investment into Singapore.”

The city-state generates around 95% of its electricity from power plants running on natural gas imported via pipelines or tankers, making Singapore highly exposed to global fuel price fluctuations. The industrial sector is typically the largest power-consuming sector in Singapore, far outpacing households, and chip makers say higher electricity bills are eating into their margins.

“Utilities are a big issue. It’s going to be a significant hit for us this year … something that we didn’t foresee. Catching any company off-guard is not a good thing,” said Chowdhury of UTAC Group, which employs around 1,500 people across three facilities in the city-state that provide third-party chip-packaging and test services.

Though the city-state boasts “know-how you won’t find in other Southeast Asian nations,” the chip executive continued, “if your affordable foreign labor costs, if your electricity costs, if those are things we don’t have access to, then not only us, but I think many manufacturing companies in Singapore will have to give it a second thought.”

Follow Nile Bowie on Twitter at @NileBowie