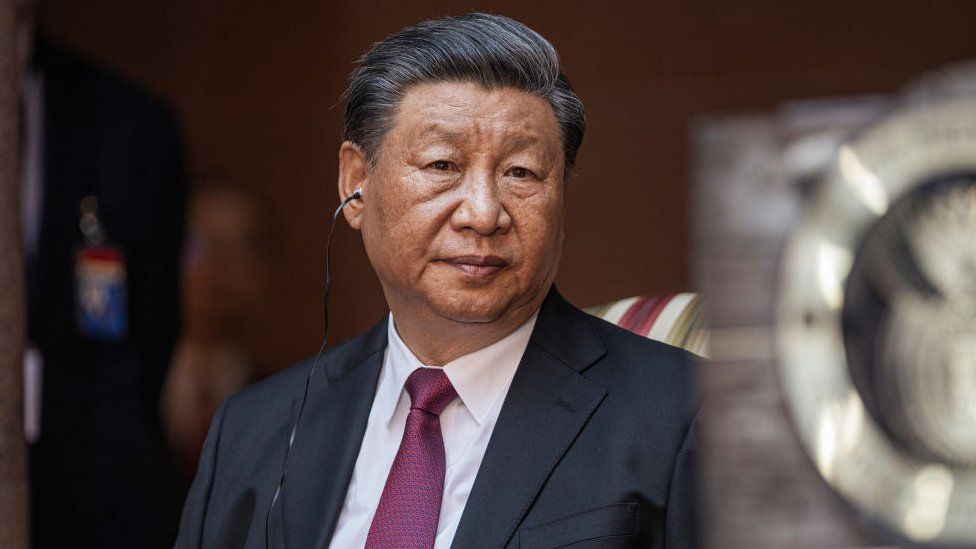

As the latest phase of Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption crackdown cuts through high-level banking and the elite nuclear rocket force, some have questioned when it might end.

The short answer: it won’t.

It has become a central plank of the system of governance for China’s leader.

And, because the anti-corruption drive has been used to remove anyone with even the slightest hint of a tendency to divert from his way of doing things, Mr Xi is sometimes characterised as an out-of-control Stalin-like figure purging left, right and centre without good cause.

But there are those who do not see it that way.

“Xi might be paranoid about high-level corruption, but his fear is not delusional,” says Andrew Wedeman, head of China Studies at Georgia State University.

“The corruption he fears is certainly real. It is likely also true, of course, that Mr Xi has capitalised on the crackdown to gain political advantage”.

Under Chairman Mao, the philosophy was that corruption could be controlled by fostering a love of the Party.

Then, during the Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin eras, the idea took hold that, if you gave people a better living, they’d have less motivation to act corruptly.

By the time Hu Jintao was in change, most Chinese people had a much better life but there were those who wanted more and were prepared to use unscrupulous means to get it, again boosting fraud on a widespread scale.

Now it feels like Chairman Xi has gone all the way back to Mao’s way of doing things, putting a huge emphasis on Party loyalty to fix the problem.

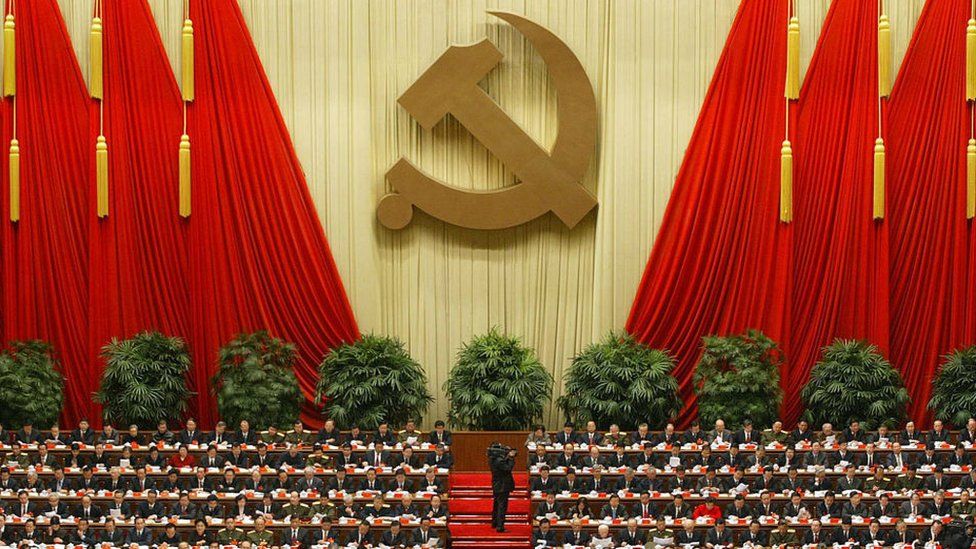

And it is via the Party that these campaigns are launched, with investigations revolving around alleged breaches of its own regulations. It’s effectively a matter of organised politics with the Party running probes however it wants.

‘People simply disappear’

It can do this because most people with high-level positions in Chinese society are Communist Party members – whether in financial institutions, sporting organisations, government departments or universities.

But once a member, you are at risk of falling foul of Party discipline charges which are at times very vague and even relate to questions of personal morality and bringing the Party into disrepute.

During this process, the teams from the feared Anti-Corruption Commission simply make people disappear.

In theory, their families are supposed to be informed before they’re taken away for questioning in secret locations, but there’s no guarantee this will happen.

One day you simply stop being seen in public and the next it is assumed you are being interrogated for an indefinite period, with no legal representation or outside accountability.

And, while this is supposed to be cleaning up economic interaction so it will run more smoothly, the crackdown could well be having the opposite effect.

“It’s reducing incentive to be creative, entrepreneurial and risk-taking, which had been the driving force of [China’s] economic growth since 1979,” political scientist Lynette Ong from the University of Toronto told the BBC.

You’ll hear the expression “lying flat” used a lot in the China of today. It sometimes refers to those in their 20s dropping out of the “rat race”, while living at their parents’ home and whiling away the hours playing video games with no great ambition in life because they can’t see a positive future.

But it’s also being used to describe officials in state-owned enterprises or the private sector who are just doing enough work to keep their jobs, nothing more, nothing less. They see it as too risky to stand out by pushing for innovation or appearing too ambitious.

“Xi wants officials to be clean and hardworking,” says Deng Yuwen, who was once editor of the influential Communist Party newspaper The Study Times.

“But with Xi focussing on corruption, they’ll just ‘lay flat’. Mr Xi, of course, doesn’t want to allow this and is demanding that they work hard lest their corruption be exposed. But the crackdown has gone on for over 10 years now and officials have become used to it. If you chase me to do work, I’ll put in a bit more effort. If you stop using the whip on me, I’ll just take it easy for a while and ‘lay flat'”.

Big money, vast bribes

But the high-profile take-downs in recent months in the finance sector are a different matter, homing in on senior executives who are accused of being very active for the wrong reasons. Among those implicated for allegedly taking vast bribes are former chairs of major banks and one time regulators. More than 100 finance sector officials have been punished over the past year.

“Too many officials have been involved in financial corruption over many decades. It’s impossible to clean this up in one or two years,” says Mr Deng. “Banking was the big target last year. It will also be that this year and the same for the coming year as well”.

According to Prof Wedeman, “We ought to expect a lot of high-stakes corruption in the banking sector because, after all, the banks are where the big money is”.

However, if banking is where the money is in China it is with the military that ultimate power resides.

The People’s Liberation Army is not the country’s army, it is the Party’s army and it keeps it in absolute control.

So the purge of generals running the nuclear rocket force as well as that of the Defence Minister, Li Shangfu, has shown just how serious China’s corruption battle has become – with unscrupulous procurement processes reportedly pushing faulty gear all the way into the nuclear arsenal.

“We’re not only talking about embezzling funds or getting kickbacks, but also subpar military equipment being purchased and potentially used by the People’s Liberation Army,” Alex Payette, the CEO of Montreal-based geopolitics consultancy Cercius said.

Alfred Wu from Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy says corruption in the rocket force would have hit Mr Xi hard.

“He had very high hopes for the rocket force,” Prof Wu told the BBC. “If I have a very strong rocket force then, in the future, if I have a war with Taiwan, it can be absolutely instrumental.”

Does he think that reorganising this crucial part of the People’s Liberation Army could actually delay any move to take Taiwan by force?

“Of course, of course!”

Yet analysts observing the anti-corruption crackdown in China have identified a gaping flaw in Mr Xi’s approach in the form of a complete absence of any systemic changes which could tackle these problems in the long run.

“The Party, despite its efforts to develop its regulatory apparatus and discipline inspection rules, etc, has failed to curb corruption. Insofar as the Party remains the sole structure to access state resources, it cannot curb infrastructural corruption,” said Prof Payette.

Some other countries have introduced genuinely independent anti-corruption bodies, increased transparency, improved the rule of law and empowered an independent media to report on corruption. China has done none of those things.

Instead, the Communist Party polices itself. What’s left is a never-ending search for bad apples without a strategy to stop them going off in the first place.

In addition to this, according to Prof Wedeman, social attitudes also need to change drastically: “Reducing and controlling corruption requires not just changes in laws, regulations and oversight but deeper changes in the culture of officialdom and the socialisation of new generations for whom corruption and bending the rules are no longer standard and acceptable practices.”

Mr Xi’s sweeping anti-corruption drive has also potentially made some officials frightened to speak out, especially those close to him who are supposed to be giving him frank and fearless advice.

For many, this became apparent after three years of the Covid crisis, when the rest of the world had re-opened but China remained closed and heavily restricted even with the economy tanking.

“No doubt there are smart people around him,” adds Prof Ong, “But his insistence on zero-Covid until massive protests broke out suggests to me that those who understand economics don’t really have his ears”.

Other China watchers fear Mr Xi has surrounded himself with “yes men”.

“At this point, Xi is not looking for frank advice. He is looking for loyalty,” says Prof Payette.

“Xi seems to have fallen prey to being constantly praised by cadres who only seek to be promoted. Looking at early Party history, he should have known that Party cadres engage in flattery to avoid being purged and gain access to the upper echelons of the Party-state apparatus.”

To an extent there is a belief that all officials are corrupt (whether they be the high-level “tigers” or the “flies” on the lower rungs) and that those who have been singled out are, for whatever reason, a threat to Mr Xi.

It is estimated that five million people have been punished in various ways during the crackdown, with some receiving warnings or fines with others getting heavy prison sentences or even the death penalty.

But rather than fostering a belief that the country is being well governed, many believe it is also trashing the Party’s reputation amongst the general public.

As Professor Wedeman put it, “I suspect that more than 10 years of the crackdown and a seemingly endless parade of ‘caged tigers’ has most likely deepened public cynicism.

“Quite simply, if you spend a decade waging a ‘life and death’ battle with tigers and – 10 years into the hunt – you are bagging as many as you bagged when you started hunting, it strongly suggests you are not hunting them to extinction and might not have even significantly reduced their numbers.”