Relations between the United States and China seem chillier and chillier, but you’d never have known that reading this item that appeared on China’s Foreign Ministry website last May:

President Xi Jinping has recently replied to a letter from Ms Sarah Lande, a friend of his in the US state of Iowa. Xi Jinping pointed out, “I visited the beautiful state of Iowa twice, and have forged an indissoluble bond with the city of Muscatine.

The Chinese and American people are both great people and our friendship is not only a valuable asset, but also an important foundation for the development of bilateral relations.

The Chinese people are ready to keep on joining the American people in strengthening friendly exchanges, pushing forward mutually beneficial cooperation and jointly promoting the well-being of the two peoples.”

Xi Jinping encouraged Ms. Lande and his other old friends in the state of Iowa to continue sowing the seeds of friendship and making new contributions to the friendship between the two peoples.

It would be easy to view this remarkable item as a cynical attempt by Beijing to improve Xi Jinping’s image. China’s leaders appreciate that the Xi whom people outside China know is the Xi who imprisons Uyghurs, denies Hong Kong promised freedoms, crushes domestic dissent, abandons market reforms, threatens Taiwan, and gives the Communist Party an ever more central role.

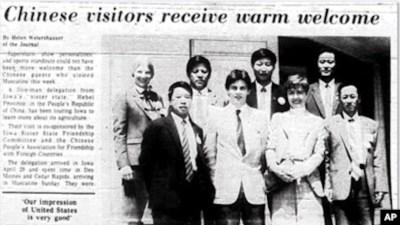

Yet while they don’t make him Mr Nice Guy, there is no reason to doubt Xi’s warm ties to Iowa, which he visited when he was a county official in 1985 and again as vice president in 2012.

People are complicated. Even Attila the Hun is said to have had a soft side.

What’s open to doubt is the relevance of those ties to international affairs. Amid the hoopla surrounding Xi’s appointment to an unusual third and possibly lifetime term as China’s leader, it’s fair to ask whether his connection with Iowa as a person has affected him as a politician.

In general, what is the impact on statesmen of personal contact with foreign lands and people?

The precedent that comes to mind is Isoroku Yamamoto, the Japanese admiral who planned Japan’s 1941 sneak attack on Pearl Harbor. Yamamoto had studied at Harvard and served two tours in Washington as naval attache.

Knowing America’s industrial might, he opposed war with the US. Ordered to plan an attack despite his misgivings, he decided Japan’s only chance was an early knockout blow. Otherwise, America’s ability to build ships and planes would prove decisive in a protracted US-Japan war.

It was, then, Yamamoto’s knowledge of the US that led to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Xi Jinping isn’t planning a military attack on the US – or so Americans must hope. But his 10 years as China’s leader have felt like an attack on democracy, freedom, rule of law and other American values. Under Xi, China is challenging the world order fashioned by the United States and its allies.

When Xi visited Iowa in the 1980s, did anyone guess he would end up like this? Terry Branstad didn’t. I asked the former Iowa governor that question at the DTN Ag Summit last December. He seemed as baffled as anyone by Xi’s evolution.

Branstad has had a cordial personal relationship with Xi since the 1980s. When Branstad arrived in Beijing as ambassador to China during the Trump administration, Xi and his wife had the Branstads over to dinner. Still, Branstad was hard pressed to explain how a guy known as a reformer when he was a lower-level official came to seen as promoting heavier-handed Communist Party control as president.

Certainly Xi’s fondness for Iowa hasn’t prevented US-China relations from going south since he became president in 2012. They’re so chilly now that some pundits even talk of a “new Cold War.”

That’s an analogy worth contemplating. In some ways, it’s off the mark. During the Cold War, US-Soviet trade was minuscule. US-China trade is enormous.

Although both countries are trying to rely less on the other, they remain each other’s largest trading partners. For US agriculture, China is by far the number 1 export market.

Leaders in both countries refer to each other as competitors, not enemies. President Biden’s latest National Security Strategy calls for “out-competing China.” By contrast, it says Russia needs “constraining.”

Some aspects of the relationship do recall the Cold War, though. One is the unanimity of opinion in Washington, where hawkishness has become the only safe China stance. Speaking up for better relations would be political suicide, like being “soft on Communism” during the Cold War.

Then there are export controls. The Americans used them to deny the Soviets access to US technology. Now the Biden administration has imposed restrictions on exports of advanced semiconductors and chip-making equipment to China.

A scary similarity involves crisis management. With tensions over Taiwan running high, a misunderstanding could easily trigger an unintended war. Yet according to a retired senior diplomat who was involved in China policy, the US and China have a “highly attenuated ability to deal with a crisis” with “no reliable military-to-military communications.”

Only after the 1962 Cuban missile crisis did the US and the Soviets develop a crisis-management mechanism. New Cold War or not, the US and China shouldn’t wait for a crisis.

Former longtime Wall Street Journal Asia correspondent and editor Urban Lehner is editor emeritus of DTN/The Progressive Farmer.

This article, originally published on October 21, 2022, by the latter news organization and now republished by Asia Times with permission, is © Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.