One of India’s prettiest cinemas looks like a dollop of pink ice cream that’s frozen mid-melt.

But nothing about its exterior prepares you for what’s inside: futuristic chandeliers; a ceiling that looks like some sort of glowing space bug; stucco-decorated walls and glass-panelled railings lit up with warm yellow lights. It’s a heady mix of the ancient and hypermodern.

This is the iconic Raj Mandir cinema in Jaipur city in the western state of Rajasthan: a single-screen cinema that opened its doors in 1976, but still runs houseful shows and is a popular tourist attraction.

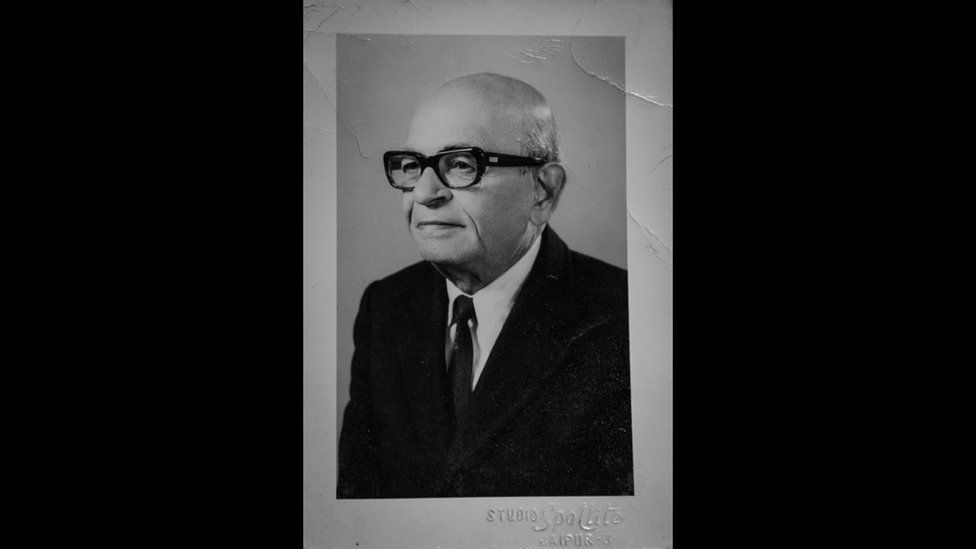

Yet, the man who designed this marvel of a theatre is shrouded in mystery. Not much is known about Waman Moreshwar Namjoshi or WM Namjoshi – an interior designer who worked on over three dozen single screen cinemas across India between the 1930s and 1970s.

Many of these were built in the flamboyant Art Deco style – a modernist design style that broke rules and celebrated the new. “These buildings featured sleek lines, inviting curves and design elements that spotlighted the latest technologies and building materials of the time, like neon lighting and concrete,” says renowned architect Rajat Sodhi.

“There were elements of grandeur and fluid interiors; the sense was that we were moving towards a better tomorrow,” he adds.

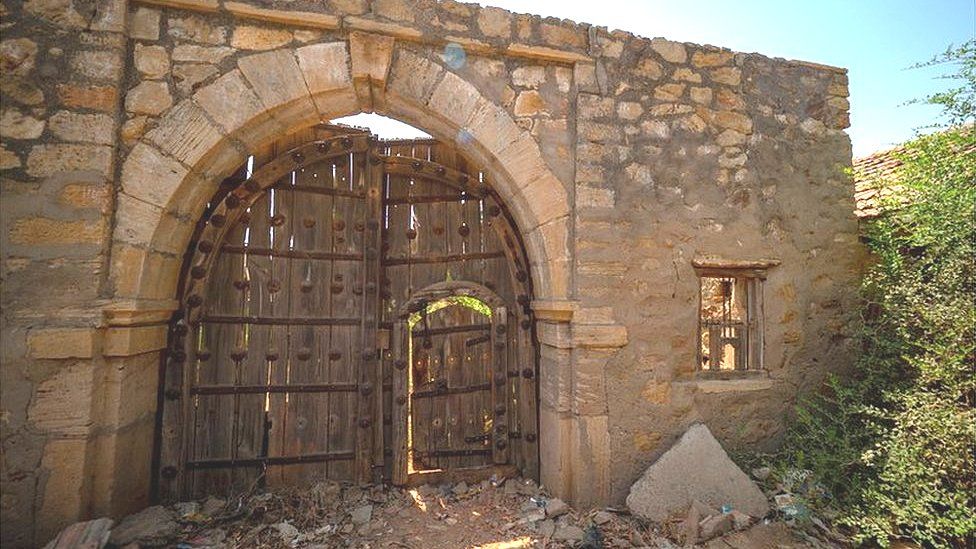

Many of Namjoshi’s cinemas have been demolished or stand in ruins, but the ones that have survived stand testament to his rare artistic genius.

Liberty Cinema in India’s financial capital, Mumbai, is one of the finest Art Deco buildings in a city that is believed to have the world’s second-largest concentration of Art Deco structures after Miami. The theatre – which opened in 1949 and held premieres of the biggest Bollywood films of the time – is famous for its frozen fountains and inventive electric lights.

Golcha Cinema in Delhi, which opened in 1954 but is now shut, featured gorgeous glass sculptures, grand curved staircases and a striking ceiling decorated with relief work.

Mr Sodhi says that these cinemas were designed to be an experience. “They were visually enticing places that transported you from the commonness of the streets and prepared you for the fantastical world of movies and storytelling that was to come,” he says.

Namjoshi crafted this atmosphere with his signature aesthetics: concealed lighting created a dreamy atmosphere; staggered ceiling designs and relief work reduced echo and reverberation so that film dialogues were crystal clear. He is also known for his wood-and-glass chandeliers and generous use of Burma teakwood and marble in his designs.

“Namjoshi was one of the most intelligent, impeccable and creative designers of his time. Though the man himself is a mystery, his work is instantly recognisable,” says Atul Kumar, founder of Art Deco Mumbai, a non-profit working towards preserving the city’s Art Deco structures.

Namjoshi was born in 1907 in Ratnagiri district in Maharashtra state to a school teacher and homemaker. His brother, Vishnu, was born four years earlier. In their teens, the brothers ran away from home and went to Mumbai.

Here, the brothers took up odd jobs, working in restaurants, as electricians and later on, as carpenters and furniture designers in British firms. On the side, they took art lessons and studied photography. In 1939, they set up Nambros – their design firm.

Three years later, Vishnu left Mumbai to set up his own firm in another city, while Namjoshi stayed on and sharpened his skills in cinema hall design. “It is likely that the brothers learnt modern design trends through the imported catalogues and magazines they were exposed to at the firms they worked at,” says Hemant Chaturvedi, a cinematographer-turned-photographer who has spent the last three years researching Namjoshi and documenting his work.

Mr Chaturvedi says that learning about the elusive architect was difficult; Google searches came up empty and many architects and designers he spoke to hadn’t heard of the man. To track him down, he dialled the 75 Namjoshis he found in a telephone directory – but found no leads.

Then one day, he chanced upon a design firm linked to a Namjoshi and decided to call the number. His calls went unanswered. But when he tried again two years later, a man picked up. “I asked him if he was related to WM Namjoshi, and he said ‘he was my late uncle'”, Mr Chaturvedi says.

Namjoshi had died in 1996 at the age of 89. The man on the phone was his nephew. By speaking to him, the architect’s granddaughter, and cinema owners who had hired Namjoshi to work for them, Mr Chaturvedi pieced together bits about the man.

“I learnt that he was a perfectionist with a short temper. If he didn’t like something he had made, he would tear it down and rebuild it over and over again,” says Mr Chaturvedi.

Namjoshi was among India’s earliest architects to transform the country’s urban landscape with Art Deco-inspired cinemas. That he spent all of his adult life in erstwhile Bombay – one of the earliest cities to be influenced by the Art Deco movement – was probably a crucial reason why he gravitated towards this style.

Being a port city, international influences travelled to Bombay’s shores swiftly and soon, the Art Deco, or style moderne movement, that originated in western Europe in the 1920s was influencing Indian architects and designers through magazines, cinema, furniture and fashion of the time, says Mustansir Dalvi, professor at the Sir JJ school of Architecture in Mumbai.

“The city also saw a phase of reclamation that freed up land and created space for planned, public-focused buildings. At the same time, concrete began replacing stone and brick masonry as a primary construction material and this allowed for structures to take on more experimental shapes,” he adds.

Mr Dalvi says that the movement gave the city structures like Liberty, which invited the ordinary citizen to become a participant in the architecture. “Unlike the more lofty Victorian Gothic buildings and gated British bungalows, Art Deco buildings invited the public to interact with it, visually and physically,” he says.

However, as newer materials and technologies emerged, aesthetics began to change and architects began to ditch ornamentation for more functional designs. These old buildings now stand as reminders of an era that celebrated change and gave the country a design landscape that reflected local influences and aspirations.

That many of the Indian architects and designers who championed this design style are not universally known and recognised is a tribute to their humility and professionalism, says Atul Kumar. “They were extremely modest, highly collaborative and hugely deferential of each other’s work. Some of them didn’t even sign their drawings with their names,” he says.

But some of their creations live on in India’s streets and anyone, literally anyone, can step in and soak in their beauty.

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC:

-

-

29 December 2022

-