Predicting the overseas travel plans of Chinese President Xi Jinping has become something of a parlor game for journalists and foreign-policy observers. Xi has not left China since the Covid-19 pandemic began, and the destination of his first post-pandemic trip – and whom he meets – will speak volumes about China’s strategic priorities.

In the Middle East, anticipation was high after The Guardian reported on August 11 that Xi was going to visit Saudi Arabia during the week of August 15. The week came and went, and no trip happened. And while close observers of China’s political cycle were skeptical of the Saudi-visit claim, the Middle East remains high on Xi’s overseas agenda.

For people who understand China’s political cycle, a foreign trip by the Chinese leader in the middle of August is usually unthinkable. The rumored Saudi visit would have collided with the annual August retreat to Beidaihe, where major Communist Party of China (CPC) policy decisions and key appointments are made. Missing that would not have been politically viable.

And this year is particularly special. The CPC’s 20th Party Congress is scheduled for October 16 , where Xi is expected to break from tradition and secure a third five-year term in office. In China, domestic politics trumps all, and securing political support at home remains Xi’s top priority.

None of this suggests that Xi isn’t planning to board the plane soon and rejoin the in-person summit circuit. At least two trips are apparently in the works.

First, Xi will likely visit Central Asia in mid-September for the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit. Second, Xi is almost certain to travel to Indonesia in mid-November for the Group of Twenty summit, where he could meet with US President Joe Biden (details are currently being negotiated).

Assuming these two trips do happen, each will carry strategic significance for China. The SCO summit, and an expected sit-down with Russian President Vladimir Putin, would signal stronger alignment with and greater support from Russia for the upcoming Party Congress. Meanwhile, the G20 summit, and a face-to-face meeting with Biden, would be used by Beijing to underline Washington’s acceptance of Xi’s third term.

The Middle East, and Saudi Arabia in particular, remains important to China in terms of energy security and for furthering the displacement of American influence in the region. But at this moment in China’s domestic political cycle, the Middle East doesn’t carry the same weight as Russia or the US. That’s why most of the Xi travel speculation is centered on potential talks with Biden and Putin.

So when will the Middle East roll out the red carpet for Xi? The most likely occasion will be the Arab-China summit scheduled to be held in Saudi Arabia late this year or early next.

Officials have been foreshadowing this trip for months, and given the buildup, it’s unlikely Xi would change course and cancel the event. Beijing could still make the summit virtual, but that would not be satisfying for the region, or for China. As such, a physical visit to the Middle East by Xi can be expected in late 2022 or early 2023.

The bottom line is that while the Middle East is not likely to be Xi’s first port of call after his self-imposed travel quarantine, it would be inconceivable for the Chinese president to give the region a pass entirely. After all, China’s other top leaders have been keeping the summit couches warm in recent months.

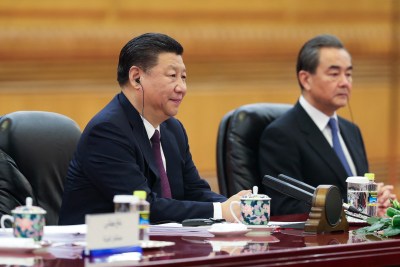

In 2021, the Middle East received more visits from Chinese leaders than any other region in the world, including three trips to 11 countries by Politburo member Yang Jiechi and Foreign Minister Wang Yi.

President Xi also hosted the Egyptian president, the Emir of Qatar, and the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi during the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics.

There are two main reasons China wants to keep the Middle East close. The first is a shared interest in transitioning from fossil fuels. As addressing climate change and achieving carbon neutrality become increasingly pressing concerns, both sides need each other to achieve their energy goals.

China requires oil and gas from the Middle East to buttress its green-energy ambitions, and the Middle East needs China as a stable and reliable customer amid market contraction. China is also an important supplier of wind and solar technology to the region.

Second, and perhaps to the dismay of the West, China and many Middle Eastern countries are aligning on political values and domestic politics. The alignment has become so strong that the Uighur issue, a human-rights imperative for the West, no longer poses an obstacle to the development of China’s ties with Islamic countries.

Although Xi didn’t visit Saudi Arabia in August, the Middle East still matters to China; its strategic interests in the region will only accelerate in 2023. As an emergent superpower, China has a growing list of overseas goals, and achieving them will require many conversations around the table.

This article was provided by Syndication Bureau, which holds copyright.

Yun Sun is director of the China program and co-director of the East Asia program at the Stimson Center in Washington, DC.