China has the world’s attention like never before, but its politics remain as opaque as ever.

Decisions are largely made behind closed doors and often delivered through cryptic announcements – so the workings of the Communist Party and the motives of its leader, Xi Jinping, are hard to decipher.

But party propaganda, despite its dry words, can offer clues about the goals of China’s most powerful leader in decades. He is now set for a third term in office, which no leader since Mao Zedong has served.

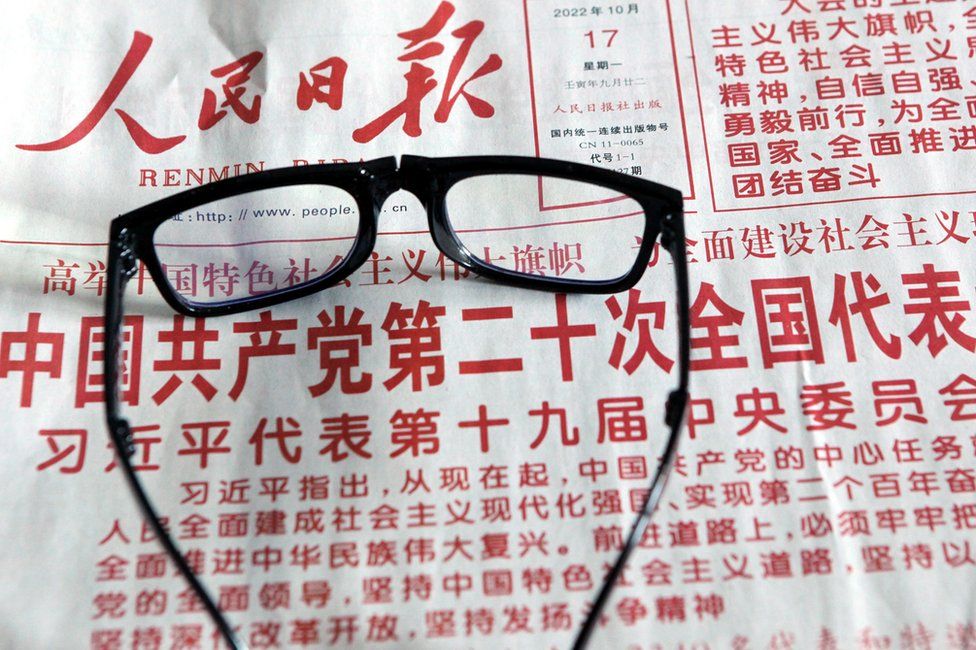

The BBC mined the People’s Daily, the biggest state-run newspaper, to identify buzzwords that define Mr Xi’s time at the helm.

The core

The concept of a leadership “core” was first used by Mao, who participated in the founding of the Communist Party and was the first leader of the People’s Republic of China.

He coined it in the 1940s before the Party took control of China in 1949. It was a time when Mao was consolidating his power within the Party, through a purge of opponents. It was not the first and would certainly not be the last, but historians see this period as the start of a Mao personality cult.

The term began to appear in relation to Mr Xi in 2016 – an occurrence that has since become increasingly common.

Before he took office in 2012, three of his four predecessors were crowned the “core” of the Party – Mao, arguably modern-China’s most powerful leader, Deng Xiaoping, who opened China to the world, and Jiang Zemin who oversaw that crucial transition through the 1990s and into the 2000s.

Hu Jintao – Mr Jiang’s successor and Mr Xi’s immediate predecessor – was never referred to as the party’s “core”. He was more a consensus builder, less a strongman, and by his time, the era of collective leadership which Deng Xiaoping had ushered in was considered a norm – or so people thought.

Given Mr Xi’s swift concentration of power, analysts say, presenting himself as the Party’s “core” was the natural next step.

“Xi Jinping needed that rhetorical consolidation of power, which is also almost equivalent to a real consolidation of power,” says David Bandurski, director of the China Media Project.

The Party, he adds, is now clearly moving towards much more personalised leadership – and back to a cult of personality.

Red country

Literally translated as “red rivers and mountains”, the phrase originated in the 1960s.

The Cultural Revolution, when a paranoid Mao effectively called for violence against anyone deemed a traitor to the revolution, brought years of upheaval to China – and the slogan “make sure the red country never changes its colour” was a deadly call to action.

But it died out in the years following Mao’s death as China embarked on economic reforms, gradually opening up to the world. The phrase had almost disappeared before Mr Xi came to power because by then the Party had retreated from people’s everyday lives.

In those years – between the 1980s and 2012 – “red country” can be found less than 20 times in the pages of the People’s Daily. But it has certainly made a comeback – last year alone, it appeared 72 times.

“The resurgence of the term is a reflection of how Xi wants the Communist Party to be the central force in Chinese politics and society,” says Neil Thomas, a senior China analyst at the Eurasia Group.

Mr Xi has repeatedly called on his countrymen and women to “introduce red genes into their blood and heart” so that “the red country can be passed on for generations”.

The Party has clearly returned to every sphere of people’s lives – and the return of the “red country” is not the only evidence of that.

Private companies listed in China are required to establish their own branch of the Chinese Communist Party. Even Buddhist monks took part in last year’s Party history quiz to mark its 100th anniversary. Cinemas are now dominated by patriotic movies.

“Xi Jinping is a true believer in the Party’s mission and it’s role in China’s national rejuvenation,” Mr Thomas says. That mission, he adds, includes “restoring China to what he sees as its historically bright position as one of the world’s pre-eminent powers”.

Anti-China forces

“Anti-China forces”, a term typically used to criticise the West and its position on China, has been around for decades. Its appearance in the People’s Daily was uncommon but would spike occasionally, usually when Beijing had a run-in with Western countries or its actions prompted an outcry at home or abroad.

But the term has been revived as China’s relations with the West and especially the US deteriorate.

Flashpoints include an ongoing trade war with Washington, allegations of grave human rights violations in Xinjiang, Beijing’s authoritarian grip on Hong Kong, and its increasingly assertive claims over Taiwan.

Nationalism within China too is on the rise. Anyone criticising the government could be perceived as “anti-China”, and people are encouraged to report such behaviour to authorities.

Negative views on China are seen to undermine its interest, Mr Bandurski says, making the Party and Mr Xi far more sensitive to and suspicious of any criticism.

Beijing often accuses Washington of trying to contain China’s power – so, Mr Bandurski says, Mr Xi fears infiltration by foreign powers, and branding any opposition as alien is an effective way to strike at opponents or rivals.

The great struggle

The term “struggle” dates back to Mao who often used it to mobilise people. During the Cultural Revolution, public “struggle sessions” saw people who were labelled “class enemies” were humiliated and often violently attacked by mobs of Mao supporters.

Mr Xi made the term “great struggle” his own – it has become a popular buzzword over the years. In 2021, it appeared in the People’s Daily 22 times more than it did in 2012 when Mr Xi first came to power.

It’s a way of evoking Mao’s time and appealing to the roots of the Communist Party, according to Zeng Jinghan, a professor of China and International Studies at the University of Lancaster.

The term is increasingly used when discussing the challenges China grapples with – both internally and externally, be it the pandemic or the “anti-China forces” blocking its path.

The “great struggle” is also a sign of a more “confrontational attitude” to tackle both challenges, Mr Thomas says.

“And it’s a rallying tool to inspire loyalty and confidence that the Party under Xi’s rule can overcome these challenges,” Mr Thomas said.

-

-

2 days ago

-

-

-

15 May 2016

-

-

-

7 October

-