Many people around the world are confused about what Donald Trump might do in his second term and whether some of the threats he made about foreign policy will be realized as a result of his success in the US presidential election.

The president-elect has threatened to make a number of significant policy changes after in office.

One of the most important issues with foreign policy is how the Trump administration may approach ending the conflict in Ukraine, in the opinion of some. Trump claimed that he could halt the conflict in a day. Different nations on Russia’s edges are concerned that any agreement that ends in a victory could lead to ideas for further military brutality, according to Vladimir Putin.

Also, if Trump abandons the US’s traditional support for the self-governing area of Taiwan, it may enable China into an invasion. The island’s status as a separatist state and its inclusion in China are seen by Beijing. But generally, US assistance of Taiwan has been a component in China holding up.

Mao Zedong’s failure after the civil war prevented Xi Jinping from establishing his reputation as the one who brought China together. In recent years, the Chinese leader has increased the pressure on Taiwan, and there are clear indications that he wants to advance.

However, neither Xi nor Putin is ensure that Trump did follow his own advice. How’s why.

A training from match idea, the scientific study of cooperation and competition, may be appropriate here – in particular, the scenario referred to as the” chicken game” or the “hawk-dove” game, which provides a model of conflict between two actors.

Because it follows the same reasoning as 1950s and 1960s contests between American teenagers, it is known as the” chicken activity.” They may drive their vehicles at high speeds, and the first to veer off to avoid a collision that might turn dangerous would be called” meat” and lose the game.

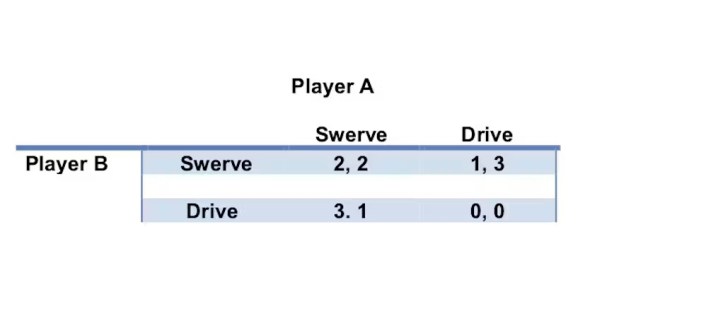

We can use a payoff matrix ( see below ) to explain the logic of this game. The speculative payoffs that could be produced by person A and player B are shown in this table. In each pair of result, person B’s return from their combined behavior is given first, followed by person A’s.

A fall is the worst possible result for both people, so this pays a total of 0 for both. When player B swerves, player A should continue driving, with the payoffs visible in the top-right cell ( 1, 3 ). In the middle left body, player B experiences the same outcome. If both turn, the reward is 2 for each person.

Swerving is preferable to colliding, but the winner is the one who drives right at his or her backwards.

Nuclear punishment can be modelled using the hen game. In this situation, striking the player first before they can drive when they swerve is equivalent to striking them first. Needless to say, when both people launch attacks together, the result is a lot worse than the zero depicted in the structure.

The trick to winning the game is to persuade your rival to keep driving at all costs. For instance, some American teenagers would pretend to throw the steering wheel out of the car to warn their rival that they could not swerve in the middle of the road if they wanted to. This basically means that you must persuade your opponent to take that risk in order to win.

This is similar to what Trump does in some circumstances. He makes significant statements about what he will do, which might include what his rivals will do after they concede defeat.

Trump also has the advantage of unpredictability. The gap between what he says and does is significant, as Michael Wolff, the biographer of his first term in office, has detailed. Wolff said in an interview:” Donald Trump is deeply unpredictable, irrational, at times bordering on incoherent, self-obsessed in a disconcerting way, and displays all those kinds of traits that anyone would reasonably say: ‘ What’s going on here, is something wrong?'”

A couple of examples from Trump’s first term make the point that the president-elect often chooses moves that, historically, other US leaders have ruled out. Sometimes these moves are successful, in other cases, they are n’t.

In 2019, Trump made a historic visit to North Korea, the first US leader to do so. Trump made the suggestion that he was the only one who could bring about a new era of friendship between the countries at this meeting. However, he made a failed attempt to form a deal with North Korea and stop the country’s nuclear program. In this case, Trump’s unpredictability did not work.

However, his unpredictability provided another example of how the US had been longing for a solution. Trump aimed to “insult and alienate US allies” in his first term, attempting to stifle the NATO alliance.

And his threats to reduce US support helped him achieve his goal of persuading NATO member nations to increase their defense spending. He had hoped exactly that.

So, Trump’s unpredictability could be a deterrent to opponents such as Putin and Xi, as they do n’t know how he is likely to react, or when he might take offence. The US president has the potential to take this personally and even have an opinion against Putin if Trump rejects a peace agreement offered by Trump to Ukraine or accepts it after starting the war in his place.

Unpredictability and carelessness can pay off in conflict and negotiation situations, according to game theory. No one is yet to decide what Trump will do next, as a result.

Paul Whiteley is professor, Department of Government, University of Essex

The Conversation has republished this article under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.