Pundits have been celebrating the Biden-McCarthy debt-ceiling deal for averting a calamitous US government default and demonstrating that compromise is still possible in today’s polarized Washington. Too bad the deal does so little to address the nation’s fiscal challenges.

Though called the Fiscal Responsibility Act, the deal “does nothing,” the Economist concluded, “to tackle the main sources of America’s fiscal irresponsibility.” Other economic analysts agreed.

If, like many Republicans, you see runaway spending as the nation’s big fiscal problem, there’s little to cheer in the deal. Federal spending will continue to increase during the next decade. Yes, it will be $1.5 trillion less than it would have been, but that’s not much considering total outlays will be $80 trillion.

If, like many Democrats, you see low taxes on corporations and the rich as the big problem, there’s nothing at all to cheer. The deal doesn’t address taxes. Indeed, the Democrats fear Republicans will soon renew their campaign for tax cuts.

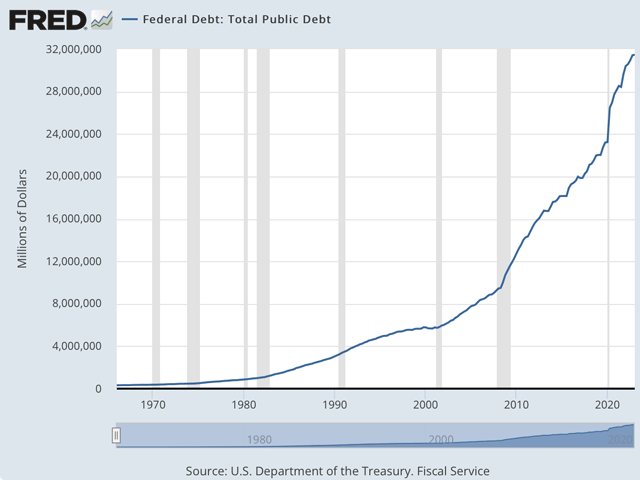

As a result of all this, a Wall Street Journal analysis projects the federal debt will rise from 97% of gross domestic product today to 115% a decade from now. Without the deal it would have reached 119%.

A big reason for this underwhelming result is that the main drivers of deficits and debt were never discussed. The negotiations focused on the 15% of the federal budget that must be appropriated annually, things like education, transportation and homeland security. (Several agriculture programs are also in this category, including rural development, research and education, and soil and water technical assistance.)

Off the table were major entitlement programs such as Medicare and Social Security, which take nearly half of the federal budget. Spending on these is expected to soar as baby boomers continue to retire. In years past Republicans have recommended cuts, but not this year. The programs are popular. Republicans feared pushing for cuts in them would cost them votes in next year’s elections.

Also off the table were defense (13% of the budget), veterans benefits (7%) and interest on the debt (7%). The eligibility requirements for food stamps were tightened for some people and loosened for others. The bottom line is that food-stamp spending could end up increasing.

As for the other big driver of deficits and debt, taxes, President Joe Biden would have liked to boost them on corporations and high earners. But tax increases, too, can hurt their proponents at the polls, and as the Republicans are dead set against them the president didn’t press very hard.

Little wonder, then, that veteran New York Times correspondent Jim Tankersley assessed the deal as “a minor breakthrough, at best.” Washington, he wrote, “is back to pretending to care about debt.”

“Pretending” sounds snarky but there’s something to the notion. What Washington cares about is not deficits and debt but spending and taxes. The Democrats want more of both, the Republicans less of both.

The ballooning federal debt is merely the result of a long period in which the Democrats have prevailed on spending and the Republicans on taxes. (The Republicans say tax cuts pay for themselves in faster economic growth but the recent ones haven’t.)

Oh, and the debt ceiling gives Republicans leverage to keep battling on the spending front. Again, it’s spending, not the debt, that they care about.

So, should we worry about the debt? It’s been growing for decades, after all, without doing the economy much apparent harm. Recently some economists have been arguing the federal debt isn’t a problem. The government, these Modern Monetary Theory advocates say, can always print money to pay it off.

Wouldn’t that risk inflation, maybe even hyperinflation? Relax, the MMT economists say. The government can always tax the surplus money out of the economy. That raising taxes is politically difficult even for the Democrats seems to have escaped them. That’s one of many reasons why mainstream economists, even those with liberal leanings, have dismissed MMT in scathing terms.

The bigger the debt gets, the greater the risk it will crowd out other spending. By the end of the decade it will hit $50 trillion, up from $32 trillion now. In not too many years Uncle Sam’s interest payments will exceed spending on defense.

And one of these times, the game of chicken Washington plays every couple of years with the debt ceiling will end badly. Very badly.

This time, the president and the speaker sidestepped catastrophe. But because they were unwilling to discuss Social Security and Medicare, on the one hand, and taxes, on the other, they served up a fiscal nothing burger.

As the Economist’s headline put it, “America avoids financial Armageddon but stays in fiscal hell.”

This article, originally published on June 12 by the latter news organization and now republished by Asia Times with permission, is © Copyright 2023 DTN/The Progressive Farmer. All rights reserved. Follow Urban Lehner on Twitter: @urbanize