If countries can be said to go in and out of fashion, then Vietnam is certainly having its moment in the spotlight.

Once better known for sitting quietly in the strategic shadows, its leaders almost unknown to the rest of the world, Vietnam is now being courted by everyone.

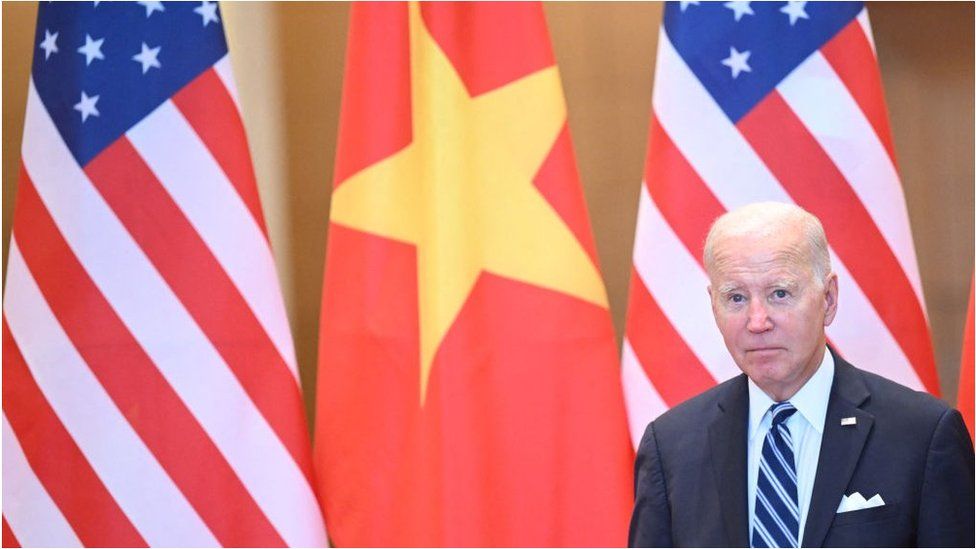

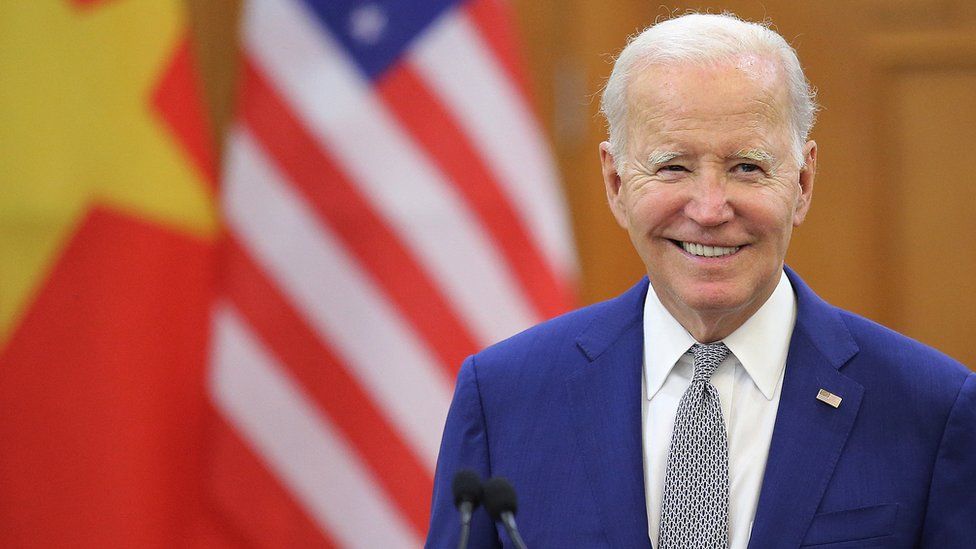

US President Joe Biden and and Chinese leader Xi Jinping both visited last year. The US saw its relationship with Vietnam elevated to the highest level possible, that of a “comprehensive strategic partnership”.

Vietnam has agreed to 18 existing or planned free trade arrangements. Its collaboration is being sought on climate change, supply chain resilience, pandemic preparedness and a host of other issues.

It is viewed as a vital regional player in the growing US-China rivalry; in the South China Sea, where it contests China’s claim to some island groups; and as the best alternative to China for outsourcing manufacturing.

What has not changed is the iron grip the Communist Party keeps on power, and over all forms of political expression.

Vietnam is one of only five Communist, one-party states left in the world. No political opposition is permitted. Dissidents are routinely jailed and the repression has become even more severe in recent years. Decision-making at the top of the party is shrouded in secrecy.

However, a leaked internal document from the Politburo of the Central Committee, the highest decision-making body in Vietnam, has shone a rare light on what the party’s most senior leaders think about all these international partnerships.

The document, known as Directive 24, was obtained by Project88, a human rights organisation focussed on Vietnam. References to it in several party publications suggest it is genuine.

It was issued by the Politburo last July, and contains dire warnings about the threat posed to national security from “hostile and reactionary forces” brought to Vietnam through its growing international ties.

These, Directive 24 argues, will “increase their sabotage and internal political transformation activities… forming ‘civil society’ alliances and networks, ‘independent trade unions’, creating the premise for the formation of domestic political opposition groups”.

The document urges party officials at all levels to be rigorous in countering these influences. It warns that for all Vietnam’s apparent economic successes, “security in the economy, finance, currency, foreign investment, energy, labour is not firm, there is a latent risk of foreign dependence, manipulation, and seizures of certain ‘sensitive areas'”.

This is alarmist stuff. In none of its public pronouncements has the Vietnamese government sounded so insecure. So what does it mean?

Ben Swanton, co-director of Project88, is in no doubt that Directive 24 heralds the start of an even harsher campaign against human rights activists and civil society groups.

He cites the nine orders at the end of the document to party officials, to police social media to counter “false propaganda”, to “not allow the formation of independent political organisations!, and to be alert for people taking advantage of the increased contact with international institutions to stir up “colour revolutions” and “street revolutions”.

“The mask is off” says Ben Swanton. “Vietnam’s rulers are saying they intend to violate human rights as a matter of policy.”

Not everyone sees it this way.

“Directive 24 does not signal a new wave of internal repression against civil society and pro-democracy activists so much as business as usual, that is, the continuing repression of these activists,” says Carlyle Thayer, emeritus professor of politics at the University of New South Wales and a renowned scholar on Vietnam.

He cites the timing of the directive, published right after the US and Vietnam had agreed to their higher-level partnership, and just two months before President Biden’s visit.

This was a momentous decision, he says, driven by the party’s fear that the impact of the Covid pandemic and the economic slowdown in China would prevent Vietnam from reaching its goal of becoming a developed, high-income country by 2045. It needed closer ties with the US to move its fast-growing economy up to the next level.

Hardliners inside the party feared the US would inevitably encourage pro-democracy sentiment in Vietnam, and threaten the party’s monopoly on power.

Professor Thayer believes the combative language used in Directive 24 was intended to reassure hardliners that this would not happen. He thinks the decision to have General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong, not just the most powerful political figure in Vietnam but also a known communist ideologue, personally sign the new partnership was intended do the same thing.

What Directive 24 does illustrate clearly is the dilemma Vietnam’s communist leaders face as their country becomes a global manufacturing and trading powerhouse.

Vietnam is not large enough to do what China has done, and seal itself off behind its own “great firewall”. Social media platforms like Facebook are easily accessible there; Vietnam needs foreign investment and technology to keep growing quickly and cannot afford to cut itself off.

Some of the free trade deals Vietnam has agreed to, like the big one with the EU finalised in 2020, come with human and labour rights clauses attached to them. Vietnam has also ratified some of the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) conventions, though notably not the one requiring freedom of assembly.

But Directive 24 suggests it is reluctant to honour these clauses.

In it, the party demands explicit limits on how independent trade unions can be, ordering officials to “strictly pilot the establishment of … employee organisations; take proactive initiatives when participating in the International Labour Organization’s Convention that protects freedom of association and the right to organise, ensuring the ongoing leadership of the Party, leadership of party cells, and government management at all levels.”

In other words, yes to co-operation with the ILO, a firm no to any trade union which is not controlled by the party.

Ben Swanton argues that Directive 24 shows would-be Western partners of Vietnam that their agreements on human or labour rights are nothing more than a fig-leaf, politely covering the deals they have made with a political system incapable of respecting individual rights.

Which civil society groups, he asks, will be allowed to monitor these free trade agreements, when we have already seen six environmental and climate campaigners jailed on spurious grounds at a time when Vietnam has just signed a huge energy transition partnership with Western governments?

There was a time, several decades ago, when one party Marxist-Leninist states were thought by many to be the future, bringing modernity, progress and economic fairness to the world’s poorest societies.

Today they are a historical anomaly. Even China is seen as a political model by very few, however admired its economic successes may be.

Vietnam’s leaders are hoping to pull off something of a conjuring trick; maintaining the strict control they have long held over the political lives of their people, while at the same time exposing them to all the ideas and inspirations that may come from overseas, in the hope that these will keep the economic fires burning bright.

Related Topics

-

-

11 December 2023

-

-

-

10 September 2023

-

-

-

17 January 2023

-