Uzbek voters passed a referendum last April extending the presidential term of office from five to seven years and allowing the current president, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, to call a snap election. He lost no time in doing so.

According to the Central Election Commission, he bagged 87.1% of the vote on July 9.

The total is impressive, as it was bound to be considering he could plausibly claim credit for a strong economy and domestic peace and tranquility, had the state apparatus and media behind him as well as various “powers of incumbency,” and was fortunate enough to be facing a slate of hapless, inexperienced candidates.

But is his vote total credible?

The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe hinted at the absence of meaningful political opposition. Its Election Observation Mission noted that the “early presidential election was technically well prepared but took place in a political environment lacking genuine competition.” Fair enough, but that hardly settles the matter of electoral credibility one way or the other.

Landslide victories, whether in Uzbekistan or elsewhere, may or may not call into question the legitimacy of the electoral process, but they do raise doubts about the viability of challengers and the dearth of capable alternative choices (see my Asia Times article “Kazakhstan presidential vote – scam or real deal?”).

But one cannot discount the possibility that Mirziyoyev’s victory reflects his personal popularity and demonstrated ability to govern effectively in a nascent democracy.

Consider the case of India’s Narendra Modi. He had a personal approval rating of 87% when he took office in 2014 and his government’s approval rating stood at 93%, according to Pew Research. Now, eight years later, his personal popularity stands at 73%, according to The Times of India.

Or take Hungary’s Viktor Orban. Last year, he won his fourth consecutive electoral victory, handily defeating his opposition, much to the consternation of Brussels and the international media.

In parliamentary systems, it is rare to achieve an absolute majority, but Modi and Orban have done so several times in a row. While the opposition alleges that their victories were the result of bullying, intimidation and fraud, it is hard to prove that a head of state’s electoral triumph was bogus just because he won by a huge margin. It could just as well be that voters approved of his policies, governing skills, and personal traits.

Advantage goes to the president

In the run-up to the election, Mirziyoyev was able to exploit his advantage as a recognized international statesman, which none of his opponents could begin to do. In Uzbekistan, he is known as a skilled head of state who represented the country’s national interests and aspirations without kowtowing to the Great Powers or taking sides in the so-called Great Game.

Over the past months, his trips overseas have boosted his domestic prestige. Who else could have met with Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi (a move not viewed in Uzbekistan as evil in itself) or landed major agreements with the other Central Asian republics and the European Union or expanded pan-Turkic engagement with the support of the presidents of Azerbaijan, Tajikistan and Turkey?

What’s more, Mirziyoyev tapped into an emergent national populism that rejects neoliberal economics and refuses to sacrifice the common good to the gods of efficiency and the interests of global capital.

Social and political stability

During the campaign, Mirziyoyev took credit for a relatively strong economy and rode it to victory. The International Monetary Fund recently projected real GDP growth this year of 5.3%.

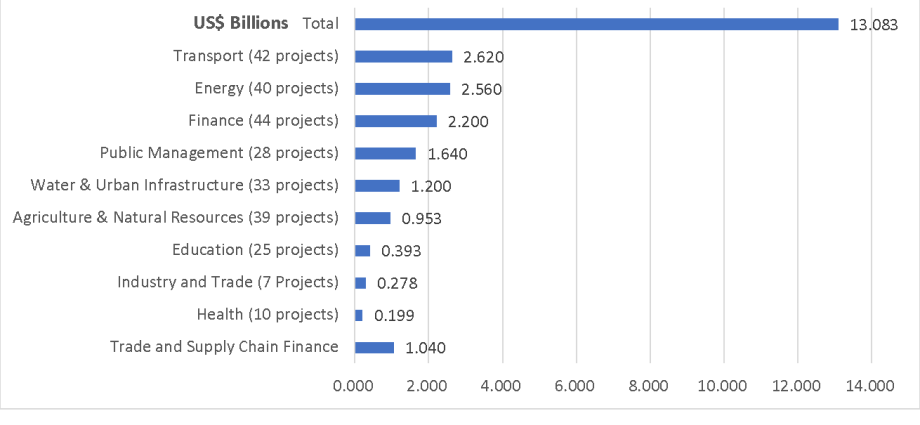

Mirziyoyev met this summer with the vice-president of the World Bank and could point to significant progress in developing bilateral partnerships worth some US$11 billion. He also capitalized on major investments from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the Asia Development Bank.

Over the past several years, Mirziyoyev has been working – with considerable success – to transform the country’s largely Soviet-style economy to one based mainly on free enterprise. In so doing, he has resisted intemperate calls for the total sell-off of Uzbekistan’s national assets to the usual assortment of carpetbaggers, leeches and no-goodniks who regularly materialize in Tashkent preaching the Gospel of Progress.

Mirziyoyev’s call in May for a Third Renaissance resonated with the people.

His pitch “to build new schools, kindergartens and hospitals, to raise the quality of education and medicine, to address the problems of water and energy supply, roads and transportation, to increase the number of workplaces, to create the new opportunities for entrepreneurship, and to ensure justice, to eradicate bureaucracy and corruption” might have rung hollow in view of the country’s lamentable legacy of corruption and nepotism, but apparently did not.

Deeds over words

Although Mirziyoyev’s access to the media gave him a decided advantage over his opponents, that’s the case whenever incumbents are up for re-election. Even if ballot-box stuffing and/or other forms of fraud and “administrative measures” were employed, they may have padded the president’s total but probably didn’t make much difference.

It makes more sense that he convinced the electorate, just as Modi and Orban have done, that he would continue to reform the economy without abandoning the poor and the middle class, increase their access to credit, medicine and education, manage the Great Powers at a time of unprecedented peril, and chip away at decades of ingrained corruption and nepotism.

Interestingly, the major media’s coverage of the election has been unusually muted, signaling that Brussels and London may be changing their emphasis in dealing with Tashkent – more carrot and less stick.

For Washington’s part, the US Embassy, in its post-election statement, could only say that it “notes” popular support for Mirziyoyev while urging respect for the rule of law, checks and balances and individual rights.

Be that as it may, Mirziyoyev’s challenge now is to breathe life into his electoral promises and stay out of foreign entanglements. He must carry on with the transformation of society and the economy without selling out the poor and emergent middle class. If he fails to do so, the goodwill he now commands is likely to evaporate quickly.