NATO members and other western countries are stepping up their supply of weapons to Ukraine. The UK recently pledged to send 14 Challenger 2 tanks, while the US has promised 31 Abrams tanks, and is sending older models to get them to the battlefield as soon as possible. Germany has dispatched 14 of its renowned Leopard 2 tanks.

Other nations have or are in the process of sending anti-tank and anti-air systems, artillery pieces, drones and tanks. These modern sophisticated weapons will be key to the success of Ukraine’s spring counter-offensive which is believed to be poised to begin.

But providing all this different equipment made in different countries brings its own challenges. Ukrainian troops need to learn how to operate the new equipment and they will need supplies and replacement parts. And troops fighting on the ground will need to learn how to tell them apart in a confusing and fast-paced environment.

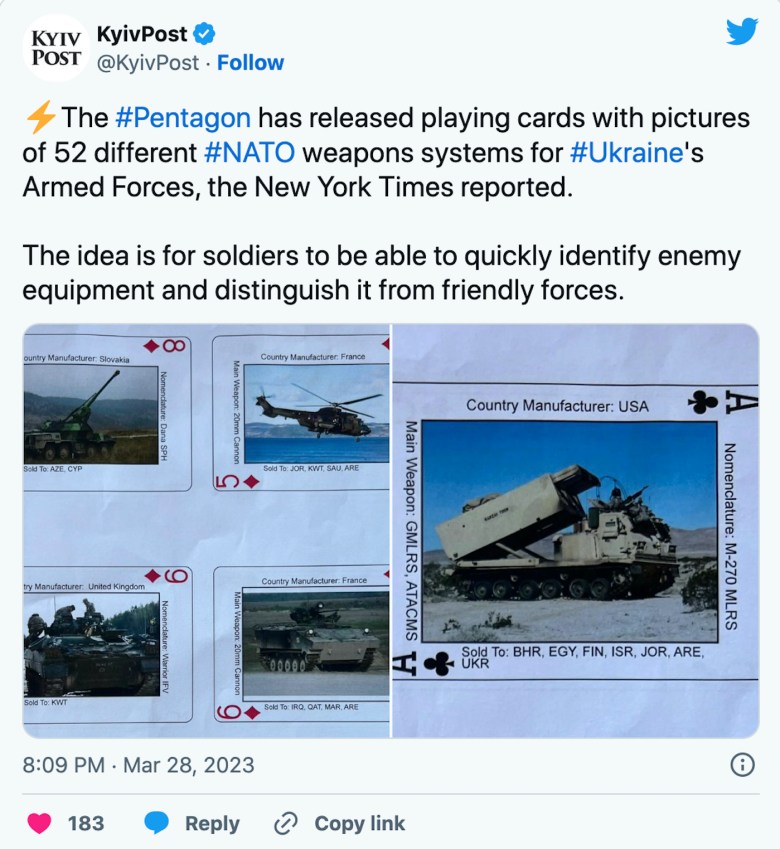

To try to overcome the challenge of identification, the US government has issued a deck of playing cards with pictures of various different pieces of hardware to help try to minimize “friendly fire” incidents.

According to a report in the New York Times, the deck has images of 52 different NATO-made tanks, armored personnel carriers, trucks, artillery pieces and other weapons systems. Major Andrew Harshbarger, of the US Army’s training and doctrine command, said the idea was to enable soldiers to quickly “identify enemy equipment and distinguish the equipment from friendly forces.”

Both sides have been plagued by the problem of friendly fire. In December, Russian news agency Tass reported that Ukrainian army units shelled each other’s positions in a battle at Kremennaya, in the east Ukrainian region of Luhansk.

Ukrainian sources, meanwhile, have reported several friendly fire incidents involving Russian units attacking each other. These include, according to a report late last year from the Royal United Services Institute (Rusi) Russia’s air defense systems engaging their own aircraft.

While the ID card system will undoubtedly help Ukrainian forces from destroying new equipment sent by its allies, it will not prevent this entirely. Battlefields are fast-moving and confusing environments where decisions have to be made in split seconds – often with very little corroboratory information.

An additional problem that may make the battlefield a more dangerous place is that communications between equipment from different suppliers are not always possible. This adds to the problem of telling friend from foe in the heat of battle.

Fog of war

The problems of identification on the battlefield and resultant friendly fire incidents are nothing new on the battlefield. In the 19th century, armies wore brightly colored uniforms in order to be seen through the smoke that was generated by the heavy musket and cannon fire that characterized warfare at this time.

Even with the improved radio communications of the second world war, there were often friendly fire incidents, particularly when ground attacks were conducted by aircraft. The relatively fluid and fast-moving battlefield, particularly in northwest Europe after D-Day in June 1944, led to many accidental attacks on friendly forces.

One of the most famous of these was the attack by US Army Air Forces on Saint-Lô in July 1944. Many of the US heavy bombers used dropped their payloads short of the German lines, killing more than 100 US troops, including General Lesley J. McNair – at that stage the most senior US officer to be killed in combat in the war.

Friendly fire incidents can be devastating for morale in the field. When they are deployed, armed forces fully expect to be targeted by the enemy – but they expect support from their own forces. So when they are bombarded by their own artillery or bombers, it can cause a collapse in fighting spirit.

And troops that survive friendly fire incidents are often left with a serious mistrust of whichever of the services – the air force, for example, or artillery groups – that had mistakenly attacked them instead of supporting them. This was particularly a problem during America’s involvement in the Vietnam War where US troops were fighting in support of South Vietnamese units and friendly fire incidents were not uncommon.

Ukraine holds the cards

The information emerging from the battlefields is that Russian forces are suffering more from friendly fire incidents than Ukraine. This suggests certain things about the organization of Russia’s combat units.

After the initial invasion by a force thought to be between 170,000 and 190,000 experienced troops, replacements and reinforcements have mainly been poorly trained, inexperienced conscripts.

Many of the Russian units now fighting alongside each other in the field have never operated together before. There are also many fighters from militias in the pro-Russian enclaves in Luhansk and Donetsk as well as mercenaries from the Wagner Group. This has led to misidentification and increased the chance of friendly fire incidents on the Russian side.

According to a report from the Institute for the Study of War (ISW) in November 2022, Alexander Khodakovsky, the military commander of the breakaway Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR), estimated that at that stage, 60% of Russian losses since the battle for Mariupol in May last year were due to such incidents.

The ISW quoted one episode where a Russian patrol returning to its base near Donetsk on November 5 drove into a ditch that had been dug by army subcontractors which they had not been made aware of.

The report concludes: “The frequent replacement of Russian military leaders, promotion of inexperienced soldiers, and cobbled-together Russian force composition … exacerbate the fragmented nature of the Russian chain of command and ineffectiveness of Russian forces and likely contributes to frequent friendly fire incidents.”

The US has issued these sorts of cards before – but almost always to identify the sorts of weapons US troops would be fighting against. But the latest deck has the opposite purpose and shows how seriously they are taking this problem.

Matthew Powell, Teaching Fellow in Strategic and Air Power Studies, University of Portsmouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.