As the French and Chinese presidents, Emmanuel Macron and Xi Jinping, were discussing the need for more constructive international engagement to end the war in Ukraine, it emerged this week that Ukraine, too, was open to reconsidering its options.

A top adviser to Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, noted that Kiev might be open to negotiate the return of Crimea from Russia, rather than taking it by force.

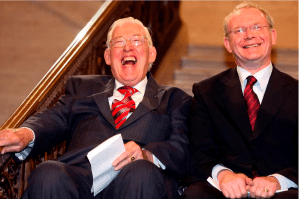

The likelihood of actual negotiations and the prospects for their success may appear slim. But things were not that different 25 years ago when, in the early hours of April 10, 1998, negotiators in Northern Ireland announced they had reached an agreement, ending a 30-year conflict that had cost more than 3,000 lives.

While the political process in Northern Ireland has been fraught with difficulties over the years, the peace has largely held. This is a considerable achievement and one that is worth reflecting on in the context of the war in Ukraine.

Three particular lessons stand out from Northern Ireland. The first, and most important, is about local leadership. Only if the parties in a conflict are genuinely committed to peace will an agreement last.

Second, international diplomacy can make a difference in nudging the sides along to an agreement. Third, there needs to be a pathway to a face-saving deal for the conflict parties that can survive contact with reality.

This last point means that not only negotiators need to agree but also those that they represent and – where applicable – the external supporters backing them. Frequently, implementation gets stuck, and then international diplomacy can play a useful role again.

If the sides remain committed to peace and the deal they agreed on creates opportunities to reengage in dialogue rather than resume violence, relapse into conflict can be prevented.

As Northern Ireland and countless other peace processes have demonstrated, a peace process does not start with the negotiations but needs to be prepared. This includes getting buy-in from leaders and followers alike that negotiations present an acceptable way forward.

Still at loggerheads

With Russia’s offensive stalled and much talk of an impending Ukrainian counter-offensive, there are no signs that either is ready yet to negotiate. Ukraine, understandably, insists that negotiations would be meaningless while Russia still occupies large parts of its internationally recognized sovereign territory.

Moscow, in turn, demands a recognition of its territorial gains, aiming to consolidate its illegal land grab at the negotiation table.

Unless the two sides fight each other to complete exhaustion – which is not likely anytime soon – sustained, well-resourced and, if necessary, muscular international mediation are required to get the parties to the negotiation table and help them to achieve a lasting peace.

In Northern Ireland, this role was partly performed by the United States – the then-US president, Bill Clinton, dispatched Senator George Mitchell to mediate the talks – and partly by the British and Irish governments who provided the time, resources, and ultimately domestic legal frameworks in which a deal was possible.

In Ukraine, there is no such impartial, mutually acceptable mediator. China may be willing to mediate, but Beijing is widely seen as backing Russia in the conflict, so Chinese mediation on its own would not be feasible.

But it would also be difficult to see mediation without China – either actively part of a mediation team or throwing its weight, for example, behind mediation by the United Nations or a revival of the earlier UN/Turkish mediation effort.

These were the talks that resulted in the original export deal for grain and fertilizer through the Black Sea and its two subsequent extensions.

Starting points

Northern Ireland is also an instructive example when it comes to pre-conditions before negotiations start. The key requirement imposed by Mitchell was that, before any party could be admitted to the talks, they had to accept six principles of non-violence.

An equivalent for Ukraine would be a commitment to the full and unconditional respect of the principles of sovereignty and territorial integrity. This is something that China has repeatedly emphasized it is committed to – including in its own position paper on Ukraine. Thus, negotiations would not need to be entered into unconditionally.

A version of the Mitchell principles would also be important in shaping a future settlement. They would prevent the simple legalization of the current status quo or a recognition of Russia’s illegal annexations of Crimea in March 2014 and four other Ukrainian provinces in September 2022.

Beyond what an eventual settlement of the war should not look like, it is also important to consider what might be possible. Even here, Northern Ireland offers some insights. On the one hand, it was not only a local agreement between the conflict parties in the region, but also one that was part of a broader agreement between the British and Irish governments on their future relations.

The war in Ukraine has all but destroyed the broader European security order and continues to affect the ongoing changes in the international order. No sustainable settlement will be possible to the war in Ukraine if it is not embedded in a reconstituted European and international order.

This must reflect the changing power balances between Russia, China and the West. And no settlement will be feasible or sustainable that does not include a credible pathway for Ukraine to EU and NATO membership.

A final lesson from Northern Ireland is that wars can only end sustainably at the negotiation table, and only if all parties’ core interests are reflected in a settlement – and the settlement itself has credible and enforceable guarantees attached. This may not be achievable in the war in Ukraine at present and perhaps not at all with Putin’s Russia.

But ultimately, responsible leaders in Kiev, Brussels, Washington, Beijing and elsewhere need to come together and work diligently towards this end and prevail against the odds just as those leaders did in Northern Ireland 25 years ago.

Stefan Wolff is Professor of International Security, University of Birmingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.