The structure of Andrew Charlton’s Australia’s Pivot to India is built on three promises: the promise of India; the promise of the Australia-India relationship; and the promise of the Indian diaspora becoming a powerful mainstream force in Australian politics.

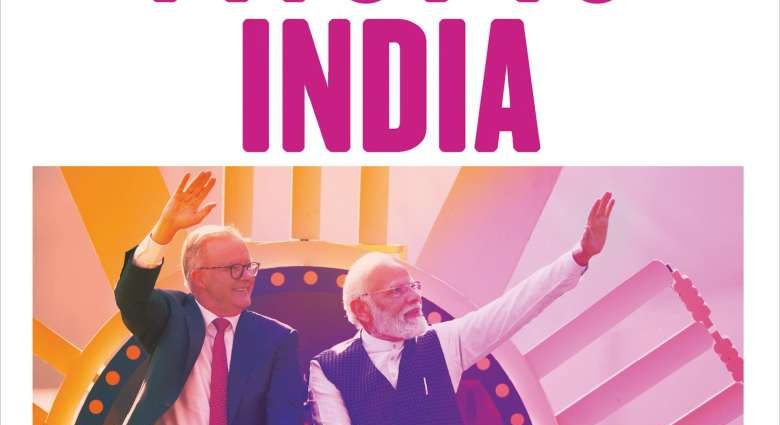

At a time when the Indian diaspora is attracting attention globally, this book – launched on Wednesday (September 27) by Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese – will be read, and read widely.

Unfortunately, the successes of the diaspora have been temporarily overshadowed by Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s accusation that Indian government agents were involved in the assassination of Hardeep Singh Nijjar in Vancouver. Nijjar was an advocate for a separate Khalistan Sikh state and the government of India believed he was involved in terrorist activities. India has categorically denied Trudeau’s charge.

Written for a discerning but popular audience, Australia’s Pivot to India is an elegant volume that treads ground familiar to those who have followed the bilateral relationship. The book serves as a primer and a political manifesto embedded in Charlton’s weltanschauung. It is written with finesse and fluency, but hurriedly: there is at least one sentence borrowed from my writings, used without attribution.

Charlton, the federal member for Parramatta and a rising star of the Australian Labor Party, is a believer. He is persuaded by India’s contemporary success and advocates the need for even greater intimacy between New Delhi and Canberra. For him, India’s rise is almost inevitable. As he puts it:

For all its twists and turns, India’s journey has brought it to a point of extraordinary promise. Just as the twentieth century was said to be the American Century, and the nineteenth century was the Age of Empire, we may well end the twenty-first century with India on top.

India is already the largest nation in the world by population. And it’s growing so quickly that by 2070 its population should rival that of China, the United States and the European Union combined. India also has the fastest economic growth of any major nation. It has the second-largest armed forces and the fastest growing military capability in the world.

Will this book, and the earlier Peter Varghese report An India Economic Strategy to 2035, do for India what the Ross Garnaut report and Kevin Rudd’s writings did for China three decades ago?

Amrit Kaal

Charlton’s book is dedicated to the people of Parramatta and the Indian diaspora across Australia. But his India-focused political vision speaks beyond the Little India of his Parramatta electorate.

For his electorate and the Indian audience of his book, Charlton is preaching to the converted. Indians, including its diaspora across the world, believe in India’s rise probably more strongly than the most generous outsider.

While the Chinese were content to emerge after just 150 years of Western humiliation, many Indians believe Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s vision of Amrit Kaal – literally the “age of immortality” – will see the return of the “Golden Age” of India after nearly 2,000 years of suppression.

Amrit Kaal refers to the period between 75 years and 100 years of India’s independence (2022-2047): a period in which it is projected that India will transition to become a developed country.

While Charlton focuses on India’s staggering demographics and its growth story, more recent news has also celebrated the country’s rise. As the Economist recently suggested:

In 2008 China used the Beijing Olympic Games as a “coming-out party” to show itself off to the world. For India, the Presidency of the G20 has served much the same purpose.

The G20 Summit in September demonstrated India’s convening power and its ability to generate a consensus at what is arguably the most important forum engaged with the globe’s most consequential problems. The summit, and 200-odd meetings held all over India this year, brought the diversity, color and genius of the Indian people onto the world stage with new confidence.

Civilizational strength

Soft power is too vulgar, too belittling a term, to describe arguably the most resilient source of India’s power: a civilizational strength often suppressed by a lack of self-confidence. This has changed, and changed in such a way that India is being perceived as a key destination for dialogue and debate over the most contentious of issues.

Despite the seductive force of realpolitik, India seems to be able to retain its core values and its space, as well as its conscience. The theme of India’s G-20 presidency – Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam: a Sanskrit term meaning one earth, one family, one future – signalled this. The theme was fleshed out in the G20 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration:

We meet at a defining moment in history where the decisions we make now will determine the future of our people and our planet. It is with the philosophy of living in harmony with our surrounding ecosystem that we commit to concrete actions to address global challenges.

Simultaneously, India has become the voice for an alternative technological vision. Just ahead of the summit, World Bank G20 Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion released a document that endorsed the transformative impact in India of Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), which allow different computer programs to communicate with each other.

It pointed out that a comprehensive data coordination system, known as the JAM trinity, has increased rates of participation in the Indian financial system from 25% in 2008 to over 80% of adults in the last six years, and that it could do for much for the world.

The government established an electronic identification system, known as the Aadhaar, which provides a unique identification number, based on biometrics, to everyone resident in India. Its electronic financial inclusion program, the Jan Dhan Yojana, lets every citizen open a bank account, which provides access to a debit card, accident insurance cover, an overdraft facility and transfer of all direct benefits from the government. All transactions can be done through a mobile phone.

This technology is part of what has come to be known as the India Stack – open-access software that can be provided to all those interested in the Global South.

India’s insistence on the African Union’s inclusion in the now G21 was also rooted in this “alternative” vision of not losing your heart, even while being dictated by your head.

Mutual understanding

All of these developments complement the argument Charlton develops in Australia’s Pivot to India and will surely find place in the next edition of the book. The bulk of his book is concerned with examining the past, present and future of the bilateral relationship.

Charlton does well to look beyond the clichés of the “3Cs”: Commonwealth, cuisine and cricket. He considers multiple sectors where there are enormous opportunities for the relationship to grow. The “3Cs” lead to the “4Ds”: democracy, defense, dosti (friendship) and the diaspora.

Business, politics, media, education and culture are also identified by Charlton as potential areas of development. As he incisively points out:

Australia’s pivot to India should aspire to build a distinctive relationship that goes beyond transactional engagement and circumstantial alignment […] the essence of the partnership is to deepen the relationship with mutual investment in common endeavors across every sphere of our interactions.

The aim should be “to increase mutual understanding, build relationships and breed familiarity.” With their “expertise and energy”, the almost one-million-strong diaspora can play a key role in cementing the relationship and is therefore a “vital part of Australia’s pivot to India.”

In fleshing out areas of cooperation, Charlton illustrates the huge potential of the Australia-India partnership. As I have written in the foreword of historian Meg Gurry’s book on the bilateral relationship (the only full-length study on the relationship, which Charlton cites extensively):

After six decades characterized by misperception, lack of trust, neglect, missed opportunities and even hostility, a new chapter in India’s relations with Australia has begun.

Consider this: in 1955, Robert Menzies decided Australia should not take part in the Bandung Afro-Asian conference, which had been organised by India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Burma (Myanmar) and Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

In doing so, Menzies – who would later confess that Occidentals did not understand India – alienated Indians, offended prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, and left Australia unsure about its Asian identity for decades.

In 2011, when I became the inaugural director of the Australia India Institute (whose seminal role in building the bilateral relationship Charlton almost completely ignores), I made a giant leap of faith. I had not visited Australia before and had little knowledge of the country.

My friends warned me I was literally going “Down Under”, soon to become irrelevant and marginal to all policy issues in India. My teenage daughters were told they risked being bashed up in school and college. My extended family was astounded.

But today I have no doubt it was one of the best decisions of my life. With not one unpleasant experience in the country, as a family, we have found Australians open, friendly, fair, accepting and generous, and the country a model of good governance.

In September 2014, when Liberal prime minister Tony Abbott visited India – the first stand-alone state visit to be hosted by the Modi government – he brought a sordid chapter of bilateral relations to a close.

When asked why Australia had agreed to export uranium to India, which is not a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, Abbott was unequivocal: “We trust you!”

No better declaration could have been made to reflect the new Australian belief in the promise and potential of this relationship, for it was the deficit of understanding and faith that severely undermined the relationship in the past.

In a reciprocal gesture, in November of that year, Modi became the first Indian prime minister to visit Australia in 28 years, adding new ballast to the relationship. Since then, the bilateral relationship has grown in strength, and across the board.

Today there are few countries in the Indo-Pacific that share so much in common, in both values and interests, than India and Australia. From water management and clean energy, to trauma research, skills and higher education, counter-terrorism, maritime and cybersecurity, there is a world of opportunities that await the two countries if they work in close coordination with each other.

Amitabh Mattoo is Honorary Professor of International Relations, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.