Three weeks after he was released from prison in December, a Tibetan town chief named Gonpo Namgyal died. As his physique was being prepared for conventional Tibetan funeral ceremonies, signs were found indicating he had been cruelly tortured in prison.

His violence? Gonpo Namgyal had been portion of a battle to defend the Tibetan dialect in China.

Gonpo Namgyal is the victim of a slow-moving issue that has dragged on for almost 75 years, since China invaded Tibet in the mid-20th era. Speech has been key to that issue.

Tibetans have worked to protect the Tibetan speech and resisted efforts to enforce Mandarin Chinese. However, Tibetan children are losing their language through membership in position boarding schools where they are being educated almost exclusively in Mandarin Chinese. Tibetan is usually just taught a few times a month– not enough to support the language.

My studies, published in a new publication in 2024, provides unique insights into the battle of various minority languages in Tibet that receive much less interest.

My study shows that language politicians in Tibet are remarkably sophisticated and driven by simple assault, perpetuated by not only Chinese regulators but also other Tibetans. I’ve even found that strangers ‘ efforts to help are failing the minority language that are at the highest risk of extinction.

Tibetan society under assault

I lived in Ziling, the largest town on the Tibetan Plateau, from 2005 to 2013, teaching in a school, studying Tibetan and supporting native non-government companies.

Most of my studies since then has focused on language politicians in the Rebgong river on the east Tibetan Plateau. From 2014 to 2018, I interviewed dozens of people, spoke freely with many others, and conducted thousands of household surveys about speech usage.

I also collected and analysed Tibetan language writings, including federal guidelines, online essays, social media posts and even music song lyrics.

When I was in Ziling, just before the Beijing Olympics in 2008, Tibetans launched a huge protest action against Chinese rule. Those demonstrations led to severe government reprisals, including mass arrests, increased security, and restrictions on freedom of action and expressions of Tibetan personality. The crackdown was largely focused on language and religion.

Years of unrest ensued, marked by more demonstrations and individual acts of sacrifice. Since 2009, more than 150 Tibetans have set themselves on fire to protest Chinese rule.

Not just Tibetan under threat

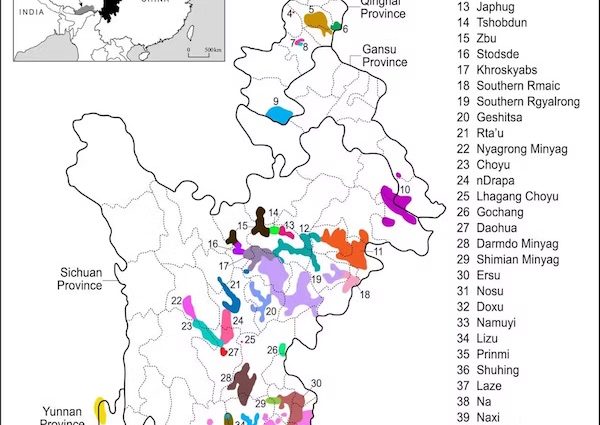

Tibet is a linguistically diverse place. In addition to Tibetan, about 60 other languages are spoken in the region. Minority-language speakers comprise about 4 % of Tibetans (around 250, 000 people ).

Government policy forces all Tibetans to learn and use Mandarin Chinese. Those who speak only Tibetan have a harder time finding work and are faced with discrimination and even violence from the dominant Han ethnic group.

Meanwhile, support for Tibetan language education has slowly been whittled away: the government even recently banned students from having private Tibetan lessons or tutors on their school holidays.

Linguistic minorities in Tibet all need to learn and use Mandarin. But many also need to learn Tibetan to communicate with other Tibetans: classmates, teachers, doctors, bureaucrats or bosses.

In Rebgong, where I did my research, the locals speak a language they call Manegacha. Increasingly, this language is being replaced by Tibetan: about a third of all families that speak Manegacha are now teaching Tibetan to their children ( who also must learn Mandarin ).

The government refuses to provide any opportunities to use and learn minority languages like Manegacha. It also tolerates constant discrimination and violence against Manegacha speakers by other Tibetans.

These assimilationist state policies are causing linguistic diversity across Tibet to collapse. As these minority languages are lost, people’s mental and physical health suffers and their social connections and communal identities are destroyed.

Why does this matter?

Tibetan resistance to Chinese rule dates back to the People’s Liberation Army invasion in the early 1950s.

When the Dalai Lama fled to India in 1959, that resistance movement went global. Governments around the world have continued to support Tibetan self-determination and combat Chinese misinformation about Tibet, such as the US Congress passage of the Resolve Tibet Act in 2024.

Outside efforts to support the Tibetan struggle, however, are failing some of the most vulnerable people: those who speak minority languages.

Manegacha speakers want to maintain their language. They resist the pressure to assimilate whenever they speak Manegacha to each other, post memes online in Manegacha or push back against the discrimination they face from other Tibetans.

However, if Tibetans stop speaking Manegacha and other minority languages, this will contribute to the Chinese government’s efforts to erase Tibetan identity and culture.

Even if the Tibetan language somehow survives in China, the loss of even one of Tibet’s minority languages would be a victory for the Communist Party in the conflict it started 75 years ago.

Gerald Roche is a lecturer in linguistics at La Trobe University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.