Ruchelle Barrie remembers feeling out of place in school.

Her name was frequently spelt and pronounced incorrectly and her fluent English made her stick out among her classmates – who were more comfortable speaking Hindi or Marathi – in the Indian city of Mumbai.

But with that spotlight came questions: Where are you from? Is your family from India? What’s an Anglo-Indian?

The last one was the toughest to answer, so she learnt to dodge it, distancing herself in public from what was a “core aspect” of her identity.

The term Anglo-Indian commonly refers to people with British and Indian parentage. But legally, it means Indian citizens who are of European descent on their father’s side – which means that their paternal ancestors could be British, French or Portuguese, reflecting the long history of colonisation in India.

Ms Barrie, now 30, is of French lineage on her father’s side and British on her mother’s – she still has questions about her identity and where she really fits in.

“But now I’m more comfortable with it and want to know more about my ancestry,” she says. So she has joined a Facebook group for Anglo-Indians, where she asks questions about the community and its culture.

Ms Barrie is among several young Anglo-Indians who are trying to learn more about their roots and preserve their community’s cultural identity, which many fear is at risk of being forgotten.

Some are researching and documenting their family’s history, and rekindling ties with long-lost relatives; others are finding ways to preserve shared memories and old recipes. In the process, they are finding new ways to foster a sense of belonging within the dispersed, dwindling community.

Experts say that the number of Anglo-Indians have steadily dropped since 1947, when the British left India, but there are no official numbers that capture this. India’s last census in 2011 counted only 296 Anglo-Indians, a number dismissed by community members as “ridiculous”.

Clive Van Buerle, a governing body member of the All-India Anglo-Indian Association, says that their member count suggests there are around 350,000-400,000 Anglo-Indians in the country.

Many migrated to countries such as England, Australia and Canada, especially in the years after India’s independence in 1947. Many have also married outside the community in the decades since, leading to dilution and intermingling of cultures.

The history of the Anglo-Indian community can be traced back to the 16th Century, when the Portuguese colonised parts of India. Author Barry O’Brien writes in his book, The Anglo Indians: A Portrait of a Community, that the Portuguese encouraged soldiers to marry local women to “create a community that would be loyal to the colonisers, yet comfortable living in the colonies”. Later, the British also adopted this strategy.

“The Anglo-Indian identity developed out of this fusing together of eastern and western cultures,” says academic Merin Simi Raj.

But this blending of cultures has also been a source of discomfort and alienation.

“Historically, the community was discriminated against by the British for their skin colour and mixed race. They were also viewed with suspicion by native Indians because of their loyalty to the crown,” Ms Raj says.

That feeling of alienation hasn’t entirely disappeared – Anglo-Indians were outraged when their quota of two parliamentary seats was scrapped in 2019.

“It’s like your identity is not acknowledged by your government,” Mr Van Buerle says.

While Anglo-Indian associations advocate for political representation, individuals like Ms Barrie are forging kinship and solidarity online.

Ms Barrie says she grew up in a “pukka Anglo-Indian home”, listening to country music stars Merle Haggard and Buck Owens and relishing meat ball curry, coconut rice and devil chutney. Even then, she says, she’s hungry to learn more about her community, from recipes for colonial dishes to information about long-lost family members.

Bridget White-Kumar, who has written several cookbooks – her most recent one has “easy recipes to cook Anglo-Indian grub in a microwave oven” – says that many young people are looking for “easier, simpler and stress-free ways” to make Anglo-Indian food.

“The Anglo-Indian community has borrowed from and contributed towards the culinary landscape of India, so it’s important to preserve our recipes by passing them on to younger generations,” she says.

Many are seeking to understand their own identity better by researching their family history.

Bangalore-based Muna Beatty and her husband Michael use genealogy websites to dig out old records – like birth, death and marriage certificates – and visit military offices, churches, cemeteries and old colonial bungalows to find out where their ancestors lived, worked or were buried.

Ms Beatty says the quest has helped them reconnect with family members across the world – they have now formed a WhatsApp group called Finding the Beattys.

For Marcelle Britto, the exercise has helped her understand her mother’s unique childhood better. Her mother, who has Irish ancestry on her father’s side, had a starkly different life from hers – she grew up in a massive colonial bungalow with dozens of domestic helpers, and was invited to tea parties and ballroom dances.

Ms Britto has managed to trace her ancestry up to the 1700s. “My mother’s stories and my own mixed identity make more sense now,” she says.

Until a couple of decades ago, Mr Van Buerle says, Anglo-Indians wanted to know about their ancestry because it could help them migrate abroad. But with the community assimilating successfully in India, people aren’t leaving India in the same numbers.

“The quest to understand one’s ancestry and identity is no longer motivated by a need for proof, but a need for meaning – it’s an exciting journey to know more about one’s self and history,” he says.

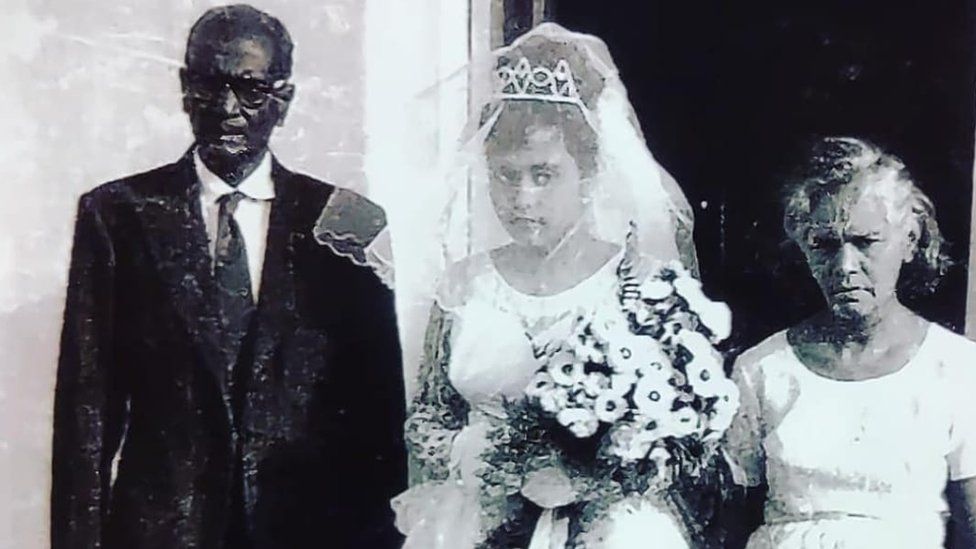

Hyderabad-based Cecilia Abraham, 47, runs a crowdsourced project on social media called Anglo Indian Stories, where people are encouraged to share family photographs and old memories.

Even though she had a very “Anglo-Indian upbringing”, Ms Abraham says she didn’t know much about her ancestry. Her father preferred to call himself “an Indian Christian”.

“One of the stereotypes surrounding the community is that Anglo-Indians drink and party too much and are not very educated,” she says. “My father didn’t want us to be seen in that light.”

Contributors to the project have described their families’ ties with India’s railways and military and what life was like before and after independence. Some talk about the pain of having lost contact with close relatives.

Ms Abraham hopes her project will help people take pride in their identity.

“When we like something, we talk about it; we take care of it,” she says. “And that’s how things, including culture, are preserved for future generations.”

Read more India stories from the BBC:

-

-

4 January 2013

-

-

-

29 December 2022

-