At the age of 31, Justin Dowswell never imagined he’d be living in a shared room in his childhood home.

He had a full-time, well-paying job in Sydney, and had rented for a decade before an unprecedented housing crisis forced him to upend his life and move back in with his parents, two hours away.

“It’s humbling,” he says. But the alternative was homelessness: “So I’m one of the lucky ones”.

It’s a far cry from the promise of the Great Australian Dream.

Where the American Dream is a more abstract belief that anyone can achieve success if they work hard enough, the Australian version is tangible.

For generations, owning a house on a modest block of land has been idealised as both the ultimate marker of success and a gateway to a better life.

It’s an aspiration that has wormed its way into the country’s identity, helping to shape modern Australia.

From the so-called “Ten Pound Poms” in the 1950s to the current boom in skilled workers moving from India, waves of migrants have arrived on Australia’s shores in search of its promise. And many found it.

But for current generations the dreams proffered to their parents and grandparents are out of reach.

After decades of government policies that treat housing as an investment not a right, many say they would be lucky to even find a stable, affordable place to rent.

“The Australian Dream… it’s a big lie,” Mr Dowswell says.

A perfect storm

Almost everything that could go wrong with housing in Australia has gone wrong, says Michael Fotheringham.

“The only thing that could make it worse is if banks started collapsing,” the head of the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute tells the BBC.

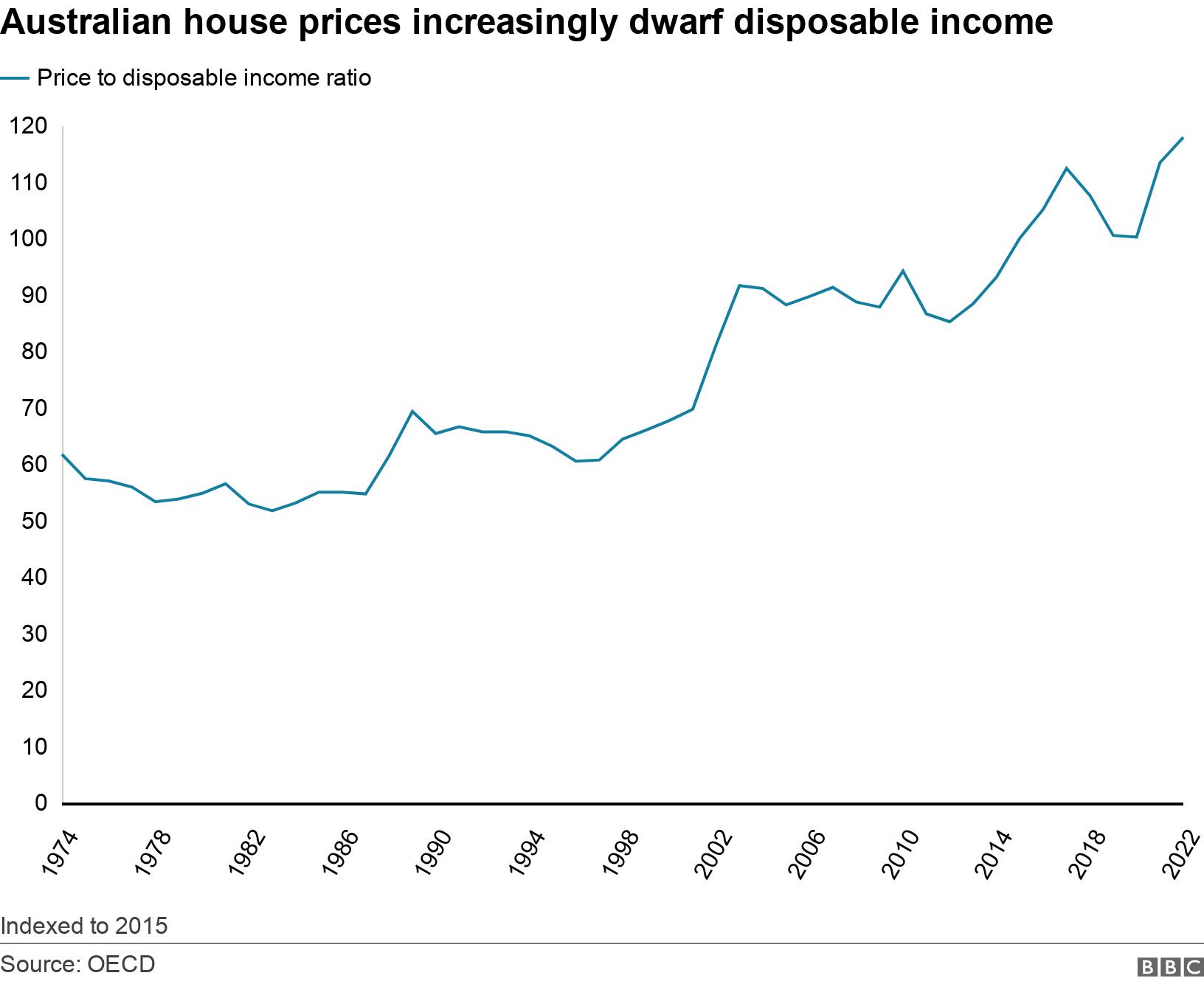

Underpinning it all is that buying a house is astronomically expensive – the average property now costs about nine times an ordinary household’s income, triple what it was 25 years ago.

It’s particularly dire for the three quarters of Australians who live in major cities. Sydney, for example, is the second least affordable city on Earth to buy a property, trailing only Hong Kong, according to the 2023 Demographia International Housing Affordability survey.

Australia has made home ownership virtually unattainable for almost anyone without family wealth. Last month the boss of a major bank, ANZ, said home loans had become home loans had become “the preserve of the rich”.

That’s left people like Chelsea Hickman questioning their future. The 28-year-old fashion designer always imagined she’d become both a homeowner and a mother, but now worries that may be impossible.

“Financially, how could I ever afford both? The numbers just do not add up,” she says.

She tells the BBC from her Melbourne shared house that despite working full-time for almost a decade, she can’t even afford to rent an apartment by herself. Her friends are in a similar boat.

“Where did it go wrong?” she says.

“We did everything that everyone said we should do, and we’re still not reaching this point where we’re going to have financial independence and housing security.”

Tarek Bieganski, a 26-year-old IT manager, laughs when asked if he thinks he’ll ever own property.

“It’s just so obviously out of reach that it’s not really even a thought anymore,” he says. “And this is coming from someone that, really, has got it pretty good.”

But with interest rates rising faster than at any time in Australia’s history, even many of those who have scraped their way on to the property ladder now live in fear of falling off it.

Foodbanks are being overwhelmed by mortgage holders struggling to keep their heads above water. Hordes of people are picking up extra jobs. Many pensioners have been forced back into work.

It’s not doom and gloom for everyone though.

The level of home ownership across the nation – while significantly dropping for young people – has overall stayed around two-thirds.

And those Australians are quite content to see house prices climb and their wealth grow.

That’s difficult to stomach, Ms Hickman says, especially given how many households – one in three – now own a property other than the one they live in.

“I understand that people are like ‘Well, I worked hard to get these millions of houses’ and blah, blah, blah, and I’m like, ‘Okay, well, good for you. I work hard too and I just want one house’.”

‘Grapes of Wrath stuff’

As a result, millions of people are trapped in the rental market, seeking to create a watered-down version of the Australian Dream as tenants.

But that’s no paradise either.

Vacancies are at unprecedented, prolonged lows – to the point that councils across the country are begging people with empty holiday homes and short-term rentals to move them on to the long-term market.

And, with the greater demand, rents are skyrocketing.

Australian news has been awash with stories of massive rent increases and images of desperate people queuing to inspect properties riddled with defects and – in some cases – obviously covered in mould.

“It’s Grapes of Wrath stuff,” Dr Fotheringham says, referring to the famous Great Depression-era novel about a family struggling to build a life.

Social or subsidised housing – once a safety net for those on low or moderate incomes – is not an option for most Australians either. The number of homes available is less than half of what is needed to meet immediate demand and wait lists are years long.

And all of this is happening at a time when natural disasters and climate effects are wiping out swathes of housing stock, making even more parts of the vast Australian continent effectively unliveable.

The crisis is tipping people into homelessness or overcrowded living conditions. Demand for housing support is so high that some charities say they’ve been handing out tents.

One Tasmanian woman told the BBC she and her four kids spent over six months crammed into her mother’s spare room after the family was knocked back for more than 35 properties while languishing on the social housing wait list.

Melbourne woman Hayley Van Ree told us her rental prospects were so bleak that her mother raided her own retirement fund to buy an apartment and is now Ms Van Ree’s landlord – eliciting what she describes as a confusing mix of relief, embarrassment and guilt.

“Friends who have parents who are in property have this kind of morbid knowledge that when their parents die, they might be ok,” Ms Van Ree says. “I hate that it’s my reality.”

Mr Dowswell is now back in Sydney, having finally secured an apartment after six months, but says the ordeal has been a massive tax on his finances and mental health.

“It was just demoralising… the more you think about it, the angrier you get,” he says.

Investment or right?

In 2023, the national conversation shifted from how expensive it is to buy a home, to how difficult it is to secure any kind of affordable home at all.

An end to pandemic-era rent and eviction freezes, record migration, rapidly escalating interest rates and construction delays conspired to leave housing in Australia in the worst state it has ever been, experts warn.

But the crisis is the result of “50 years of government policy failure, financialisation and greed”, wrote leading finance journalist Alan Kohler in a recent Quarterly Essay.

Particularly critical was what happened at the turn of the millennium, he argues. Until that point house prices in Australia had kept pace with income growth and the size of the economy – but this began to shift when the federal government introduced tax changes which incentivised the buying and selling of homes for profit.

A sharp spike in immigration and government grants pushed up house prices in that era too, but Mr Kohler says it was these tax breaks that forever changed the way Australia thinks about housing.

“It will be impossible to return the price of housing to something less destructive… without purging the idea that housing is a means to create wealth as opposed to simply a place to live,” he wrote.

Doing so will upset a large class of voters, which will take courage and innovation from policymakers, he adds.

And that’s something critics say successive governments at federal, state and local levels have struggled to muster.

Some point to decades of neglect for social housing, or the persistence with grants for first homebuyers, which are popular but don’t work as they should and actually drive up prices further.

Others argue planning and heritage laws have been too easily abused to limit developments, often by existing residents reluctant to see changes to their suburbs and investments.

Then there’s the fear of overhauling those lucrative tax incentives for property investors – with the most recent promise of reform rejected at an election in 2019 and now abandoned.

“Housing needs to be seen as an essential service and right before an investment,” Mr Dowswell says. “There is definitely a moral imperative to act… [but] selfishness will get in the way.”

National Housing Minister Julie Collins told the BBC there are “challenges” to tackle, but that her government – elected 18 months ago – is delivering “the most significant housing reforms in a generation”.

It has created or expanded schemes to help prospective buyers, though they have strict requirements and limited places. It has also promised to build thousands of new social and affordable houses – a small dent in the waiting list – and set up an investment fund to support future projects. Alongside state governments, it has pledged to create a National Housing and Homelessness Plan and beef up protections for renters.

The government is pulling other levers too: it announced earlier this month that it would halve Australia’s immigration intake and triple the fees for foreign homebuyers, both things they argue should help ease the strain.

Advocates support these changes but say they are just more tinkering around the edges of a system that needs heavy reform.

Those the BBC spoke to say that the Australian Dream has been demolished, eroding the foundations of the nation’s identity.

Australia has long thought itself the land of a fair go.

“[But] education and hard work are no longer the main determinants of how wealthy you are; now it comes down to where you live and what sort of house you inherit from your parents,” Mr Kohler says.

“It means Australia is less of an egalitarian meritocracy.”

Or as Ms Hickman sums it up: “It’s rigged.”

Related Topics

-

-

8 November 2022

-

-

-

23 October 2022

-