It would be wrong to view the restoration of relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran as something that happened suddenly.

Since the Iranian Revolution of 1979, ties between the two important Muslim neighbors have been strained. For the Saudi elite the revolution was not only anti-monarchical but also a boost to the Shia sect within Islam.

For the Iranian revolutionaries, Saudi opposition was motivated largely by its intimate relationship to American and other Western elites and their interests.

This strained relationship sank to its nadir in 2016 when a respected Shiite cleric, Nimr al-Nimr, was executed by the Sunni Saudi authorities. Shia communities all over West Asia and even in Central Asia were deeply upset by this callous deed.

The execution reinforced the negative image of the Saudi government. That image was further tarnished by the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi by people allegedly linked to the apex of Saudi society.

Western elites and human-rights activists were aghast at the cruel barbarity of the assassination. A chasm of mistrust was now developing between the West and Saudi Arabia.

In the midst of all this, the US, mainly for commercial reasons, sought to increase its own oil output through fracking of shale deposits and therefore indirectly reduced the significance of Saudi oil in the global market. As a result of these and other developments, the Saudi elite in the last two or three years was beginning to feel that it was being pushed into a corner.

Ironically, the Iranian leadership was also beginning to feel isolated.

When the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was agreed by the five permanent members of the UN Security Council and Germany, on the one hand, and the Iranian government on the other, in April 2015, the Iranian people were hopeful that with financial and economic sanctions lifted, investments would flow into the land and the country would emerge as a vibrant actor in the regional and global arena.

However, that hope was short-lived, as a new US president, Donald Trump, torpedoed the JCPOA in 2018 mainly because of pressure from Israel. Iran’s economic woes became even more severe and undermined its political stability and weakened its social cohesiveness.

Iran’s internal crisis was further compounded by an incompetent leadership that lacked rapport with the masses.

Good timing

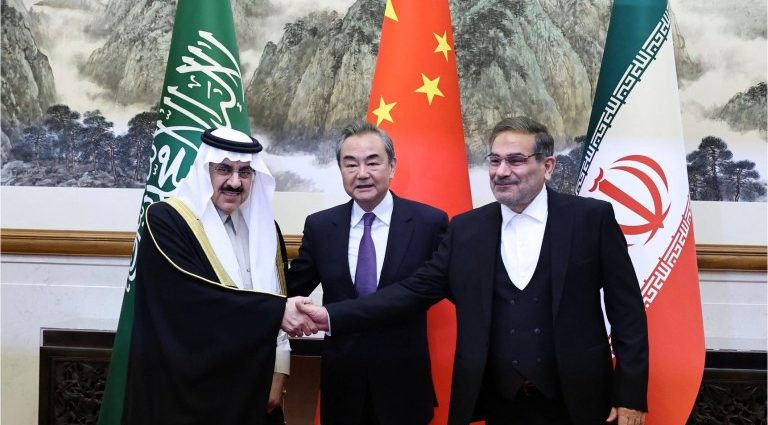

Given the colossal challenges facing the Saudi and Iranian governments, they were impelled to reach out to each other so that their mutual antagonism would not further emasculate their waning strength. China’s readiness to bring the two countries together was, given the circumstances, a bonanza.

Only a nation with the gravitas of China could have played the role of mediator. The United States’ decades-old antagonism toward Iran precluded any such role. Russia, with ties to both adversaries, could have stepped in except that its war in Ukraine was consuming all its energies.

China not only has good relations with both countries but also imports huge quantities of oil from Iran and Saudi Arabia. More important, China appreciates the fact that neither country joined the US-orchestrated bandwagon to condemn China for its alleged persecution of the Uighur Muslim minority in Xinjiang. Trying to reconcile the two Muslim adversaries was perhaps China’s way of saying “thank you” to them.

However, China’s role, significant as it is, does not hold the key to genuine restoration of ties between Saudi Arabia and Iran. It is the two countries themselves that will determine the success or failure of the Chinese effort.

The Yemen tragedy

For a start, if they can help to end a number of conflicts in the region purportedly linked to the two protagonists, it would be a good sign. It is said that current conflicts in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Bahrain and Yemen, some of which are violent, are fomented by either Saudi Arabia or Iran. Of course, other actors from inside and outside the region are also involved.

A conflict that has involved both sides is the one in Yemen. The formal government is supported by the Saudi elite while rebels opposed to it, the Houthis, are reportedly sustained by the Iranian authorities.

According to the United Nations, 150,000 Yemenis have lost their lives in the nine-year conflict. Thousands of others have perished as a result of famine and disease. If the Saudi-Iran thaw, engineered by China, can lead to the resolution of the Yemen conflict in the immediate future, a lot of peace-loving people all over the world will rejoice.

Though a variety of forces and factors are intertwined in the Yemen conflict, as in each and every one of the other conflicts, there is an underlying cause to all of them, which is related to the one most perennial and persistent dichotomy within the Muslim world. This is the Sunni-Shia dichotomy that we have alluded to.

Bridging the chasm

It must be emphasized nonetheless that the central characteristics of Islam – belief in the oneness of God; recognition of Muhammad as the last of God’s prophets; adherence to the Koranic message as guidance in this transient life; and the acceptance of divine judgment in the hereafter – continued to bind Sunnis and Shiites within the same religious community.

But the bond emanating from these characteristics sometimes succumbed to the pulls and pressures of politics and power and of personalities and vested interests who chose to give greater significance to the differences that separated Sunnis from Shiites than their similarities. This is why through the centuries it has been difficult to bridge the Sunni-Shia chasm.

Be that as it may, there have been numerous attempts to bring Sunnis and Shiites together. And there have been moments when they have forged strong bonds in facing common challenges or in pursuing shared goals.

I initiated a modest move in 2013 through my non-governmental organization JUST to get the two groups to adopt a common position on a matter of grave concern to both.

The former prime minister of Malaysia, Mahathir Mohamad, and the former president of Iran, Muhammad Khatami, were persuaded to issue a joint appeal to Sunnis and Shiites to stop killing one another, as inter-sectarian violence was rife at that time in some parts of the Muslim world.

There was very little media coverage on the Mahathir-Khatami appeal. Hardly any Muslim leader of stature responded. Even Muslim civil-society groups gave scant attention to the plea from the two leaders. In other words, a noble call to end fighting fell on deaf ears.

The China initiative on Saudi-Iran ties is different in its approach. It focuses on inter-state relations. It hopes that state actors will be prepared to use state power to reduce and even eliminate inter-state animosities.

At some point down the road Saudi Arabia, Iran and China, as well as other states, will have to deal with the ramifications of the Sunni-Shia dichotomy.

Israeli opposition

For the time being let us turn to some of the opposition to the Saudi-Iran peace plan. The loudest denunciation of the plan has come from the Israeli government.

Israel fears that the plan will work against its machinations in the region. Israel is hell-bent on isolating Iran and mobilizing all the Arab states in the region against Tehran. Toward this end, it has not only exploited the Sunni-Shia dichotomy but also the Arab-Persian division, since Iran is the only Persian state in the region.

Israel sees Iran as a threat to not only its existence, but also to the whole of West Asia, since Iran, according to Israel, is determined to build and use a nuclear bomb. Incidentally, Israel is the only state in the region that possesses nuclear bombs. Besides, Iran has repeatedly emphasized that it will not manufacture or deploy a nuclear bomb because it is against Islamic teachings.

If the Iran-Saudi accord makes it difficult to isolate Iran, it is inimical to Israel’s ambitions for yet another reason.

As a way of strengthening its position in its Arab neighborhood and within the Muslim world, Israel has always wanted to establish formal diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia. That has become more problematic now that Saudi Arabia and Iran have come together.

It is significant that Saudi Arabia has also made it clear that it will not recognize Israel as long as it does not recognize Palestine’s right to nationhood and acknowledges the right of Palestinians to return to their homeland.

It is another way of saying that Saudi Arabia will not do what other Arab states such as the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain have done in recent times in the name of implementing the so-called Abraham Accords.

US concerns

If any other nation is even more apprehensive of the Saudi-Iran bid to reconcile through China’s initiative, it would be the United States of America. It is only too apparent that China has become a major actor in West Asia.

It is amazing that it has succeeded in bringing the United States’ closest friend in the region next to Israel and its greatest foe in West Asia together through an accord and in the process enhanced its role as a peace mediator.

Indeed, a peace mediator is a role that befits the only nation in human history that has emerged as a global power through relatively peaceful means, without engaging in wars and committing wanton violence.

Perhaps it is in this role as a peacemaker that China may be able to end the protracted conflict between Israel, on the one hand, and Palestine and other Arab states, on the other. Perhaps this is how Palestinians will be able to exercise their right of self-determination and regain their dignity as a nation – something that was never possible as long as the region was under US hegemony.

This is why China’s role in restoring Saudi-Iranian ties may well be the harbinger of a new dawn in West Asia and a new era in international relations.

An edited version of this article appeared in China Focus (Beijing) on March 30, 2023.