At dawn on 19 November 2022, Muhammad Izuan queued an hour before polling began at 8 a.m.

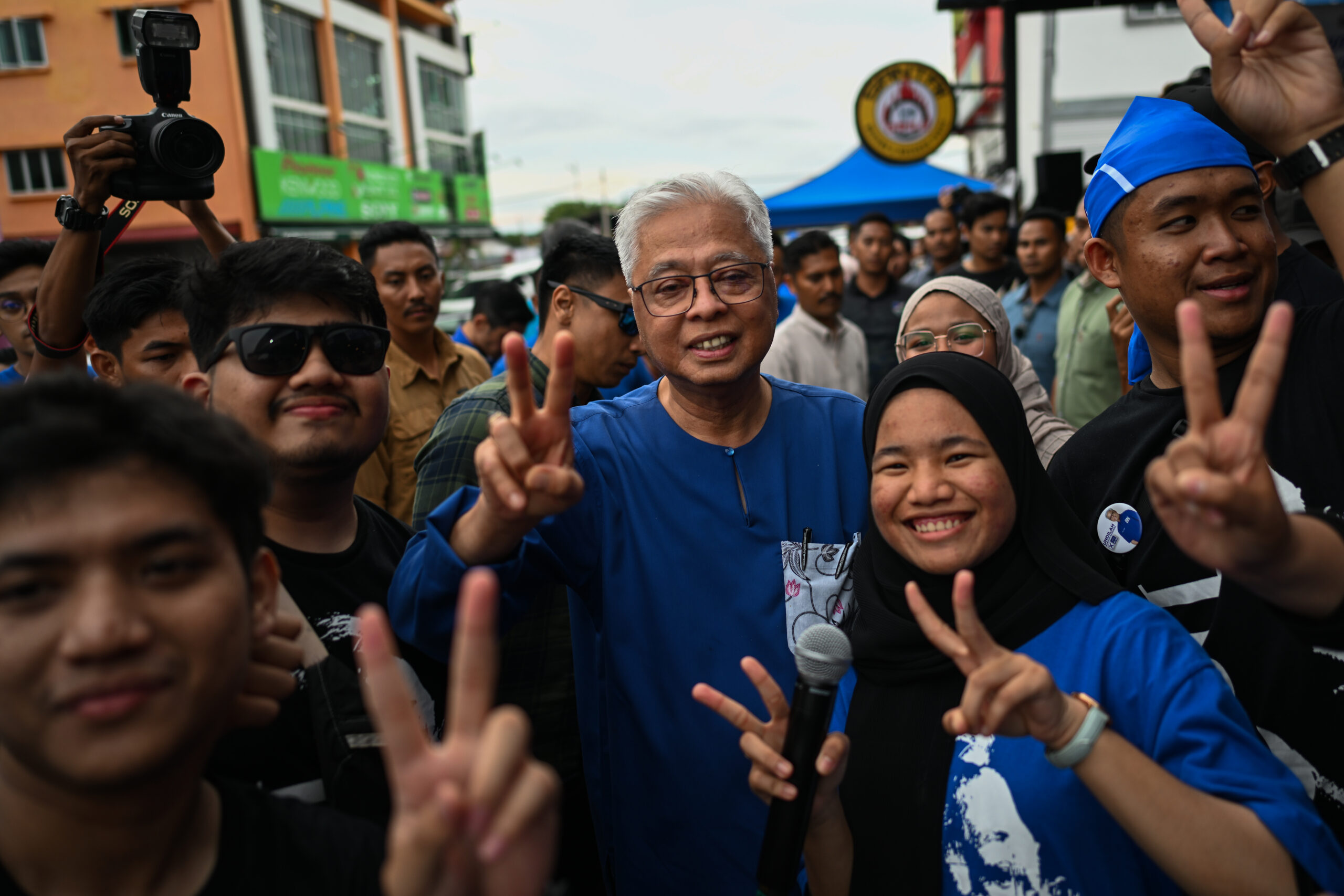

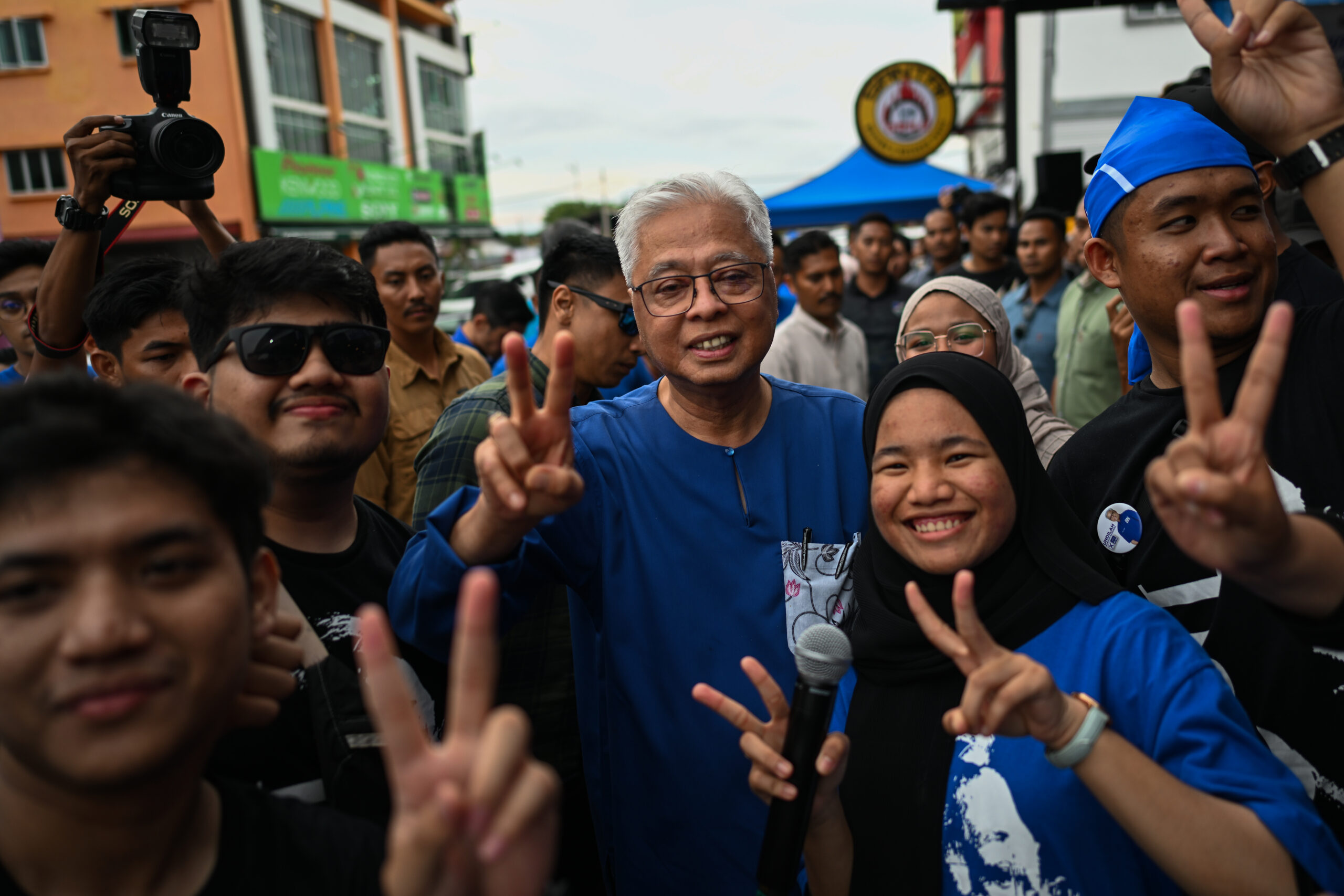

That evening, while waiting with bated breath for the results, he decked himself entirely in blue – from face mask to matching shirt and cap – an unmistakable indication of his voting choice.

“My hope for this country is that the economy will return to stability,” he said, explaining his vote for the blue-logoed, centre-right Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition party. “The entire family on both my mother’s and father’s sides have always voted for [them].”

It was the day of the Malaysian general election, and Izuan was among the 1.4 million new voters aged 18-20 who, for the first time ever, were eligible to vote. That was due to a 2019 federal constitutional amendment that reduced the minimum voting age from 21 to 18 years old.

The amendment, commonly known as Undi18, or ‘Vote 18’, plus a new, automatic voter registration scheme, added 5.8 million new voters to the country’s electoral roll. That’s about 40% of the total electorate of about 21 million.

It was a major shift, even against a backdrop of a polarised electorate that has seen three prime ministers since the last general election in 2018. In the months before last year’s polls, analysts deemed youths such as Izuan as potential “kingmakers” who could possibly shift Malaysian politics to the left.

But as the dust cleared and results came in, it appeared the youth may be just as split as the rest of the voting public. None of the three main coalitions managed to secure a simple majority of 112 seats, leading to Malaysia’s first hung parliament. Now, youth voters are reflecting on their mixed impact.

Some are hoping to shift the landscape of Malaysia’s future political landscape, which is currently split along ethnic, religious and geographic lines.

The multi-ethnic coalition Pakatan Harapan (PH), or Alliance of Hope, led the field with 82 seats. Not far behind was the new, far-right nationalist coalition Perikatan Nasional (PN), the National Alliance, which won 73 seats.

Following a string of controversies and corruption allegations, BN found it had lost considerable favour amongst the electorate, securing only 30 seats.

First-time voters, particularly those from minority groups who previously felt deprived of a voice, said after the polls that they wanted to see better representation in government.

“I voted because I think it’s a very powerful check-and-balance mechanism to remind those in power, that if you do fishy things like party hopping, and stealing the mandate from a government – you will be voted out,” said 25-year-old debate coach Deeps Kumar.

Kumar, who is a transgendered, Tamil Malaysian, voted for PH. She hoped the centre-left PH coalition would produce a government less hostile towards gender-diverse individuals, remembering a Halloween raid last year where LGBTQ+ partygoers were detained by religious authorities.

“I just want to make sure that the government in power will just focus on the economy and stability, welfare, development and stop using the queer community as this tool and very convenient smokescreen to distract from all the terrible inefficiencies,” Kumar said.

Looking beyond divisions

In interviews and surveys, young voters generally resounded a need for a stable economy and reduced corruption in the government. However, even with these apparently shared goals, the results of the polls found a very different welcome across the electorate.

While the rural youth population – who tend to be more often Muslim, ethnic Malay and favourable to conservative parties – were disappointed with the victory of PH leader Anwar Ibrahim, the 75-year-old was greeted with cheers by more diverse, young urban voters.

The division among youth doesn’t lend itself to sweeping narratives, said researcher Bridget Welsh, who specialises in Southeast Asian politics at the University of Nottingham Asia Research Institute Malaysia.

“We have to be careful not to overgeneralise them,” Welsh said. “There are different groups among young people – those that are in more urban areas, more educated or less educated youths, those with class and gender differences – all the same differences for the rest of the electorate matter among young people.”

Still, Welsh believed the high youth turnout in the 2022 elections signaled a need for change.

For first-time voter Kuala Lumpur-based Pavithrah Sambu, 25, who works in consulting, the election was exciting as it was the first time the entire family had voted.

“It’s still important to vote because it’s a more explicit way for young people, especially for new voters, to involve themselves in democracy and say, ‘Look at what is happening. We want to vote out people who have not served us,’” she said.

Sambu notes that the election results were not only swayed by youth participation, but the gaps between the rural and urban areas.

“A lot of people assume that it is only younger people who are influencing the vote, but there’s a lot of polarisation among young people as well,” she said.

Stronger youth participation

Some politicians see a kind of flexibility within the divide.

“Young people in actuality are least loyal to any political parties, and are willing to consider and experiment [with] their political choice,” said Syed Saddiq, a parliamentarian for the centre-left Malaysian United Democratic Alliance (MUDA), a party he formed in 2020.

The party’s acronym means “young” in Malay, and Saddiq lives up to that. In 2018, he became minister of youth and sports when was just 25 years old, making him the youngest federal minister since Malaysia’s independence.

For last year’s election, Saddiq said young and first-time voters turned up in droves and disrupted many seats that were previously considered secure.

“Prior to elections, many skeptics said that young people would not turn up during polling day [and] that they were disenchanted, they didn’t care and will never care, and … there’s great apathy,” said Saddiq, who was also a key figure in driving the constitutional amendment.

He believes the 2022 elections disproved this skepticism, adding that youth voters also branched out from traditional voting choices to give new candidates a chance.

As a young politician himself, Saddiq has found some challenges in being taken seriously by his senior peers. He’s been called a “greenhorn kitten” as well as “cucu” (grandchild) and “budak” (kid) by his older counterparts and other lawmakers in the house of representatives.

“Once you become a force of change, there will be a lot of resistance. That is part and parcel of the journey,” he said.

Young voters are hopeful their participation will produce better outcomes, especially among new voters.

Aliff Naif, a 24-year-old political science major at the International Islamic University of Malaysia in Kuala Lumpur, stressed the importance of political education among youths so that they make informed decisions.

As the president of his university’s student union, Naif said he organised voting simulations to help students understand how elections work.

While such programmes might not yet reach more marginalised communities, Naif believed that while student movements may not reach these demographics, the Election Commission of Malaysia can be spurred to reach out and improve political literacy among youths.

“Democracy doesn’t stop on polling day – democracy actually starts there,” he said. “I hope to see opportunities given to youths regardless of their affiliation, connection, social status, so that there can be more and more participation in politics.”