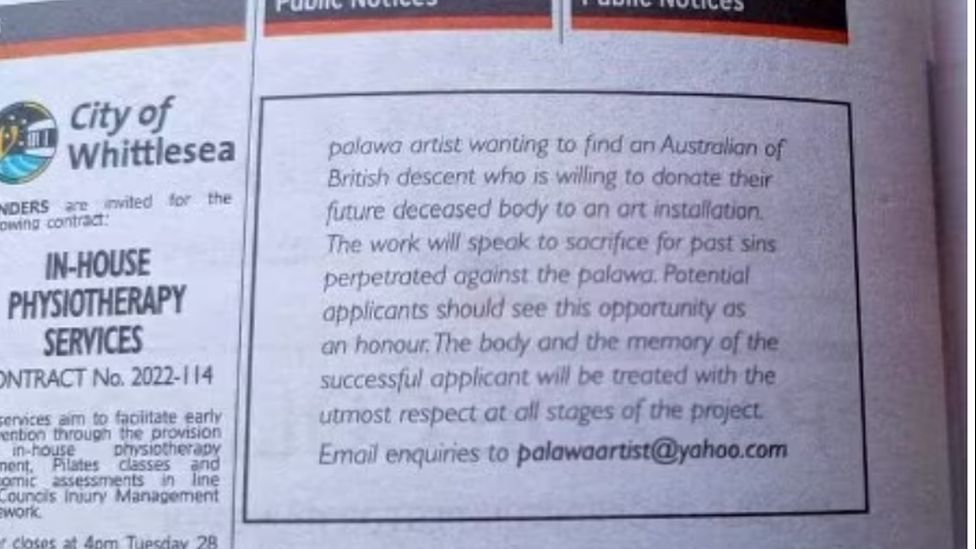

Australians browsing the The Age newspaper recently may have spotted a rather startling small advertisement.

The ad asked for a volunteer “of British descent” to donate their dead body to an art project which would “speak to sacrifice for past sins”.

Nathan Maynard, the artist behind the ad, says he wants his work to prompt reflection on one of the colonial era’s darkest episodes.

His planned work will form part of an arts festival in Hobart this November.

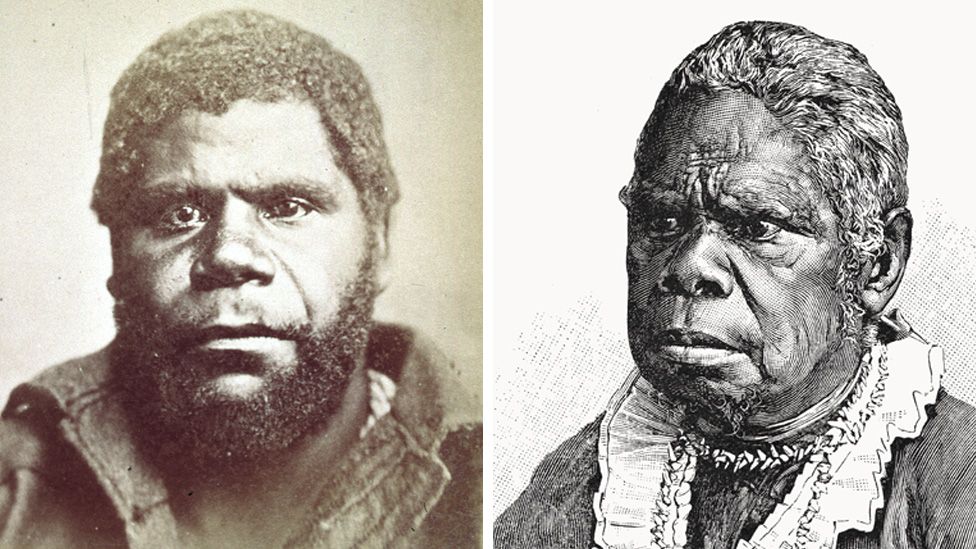

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised this article contains images of people who have died.

An Aboriginal Tasmanian performance artist and playwright, Maynard says the idea came to him when he witnessed “virtue signalling” on social media, where “everyone wants to be seen as a good person” when it comes to Indigenous issues.

“In some people, you’ve got to go, ‘what’s their intent?’ Is this for their benefit or is this for Aboriginal Australia’s benefit?”

“With social media… everyone looks great. But lost is the fact that we’ve still got how many of our people in custody. We still haven’t got that treaty [a legal agreement with the government] in this country.”

Maynard says his intention is to ask people “what would they physically do for First Nations people in this country and around the world?”

“Would they put their body on the line if they had to? Would they protest the next time an Aboriginal person is killed in custody? Will they join our protests?”

The artist says he doesn’t yet know what final form his installation, to be titled “Relic Act”, will take. The project will unfold in several stages, starting with an interview and selection process for prospective donors.

Maynard says he’s already had some volunteers. But while his advert makes clear the chosen body will be treated with the “utmost respect”, he says the act of donation is to atone for colonial “sins”.

He points to the theft, mutilation and display of the bodies of Indigenous people by European museums and institutions, beginning in early colonial times and continuing for decades afterwards.

They included William Lanne, an Aboriginal Tasmanian leader known as “King Billy”, whose body was dismembered and used for scientific research after his death in 1869.

After a dispute over who owned his remains, Tasmanian doctor and businessman William Crowther allegedly broke into a morgue, decapitated Lanne’s corpse and had his skull sent to the Royal College of Surgeons in England.

Lanne’s partner Truganini, an Aboriginal leader’s daughter who lived an extraordinary life of survival through the brutal colonial era, suffered a similar fate.

“Truganini knew that William Lanne’s head was decapitated, and she was terrified that that was going happen to her,” Maynard tells the BBC.

“She pleaded with everyone and the government not to do that to her. And what did they do? They waited for two years after her death, and exhumed her body and put it on display in a museum until the 1940s.”

Truganini’s remains were finally returned to the Aboriginal community in 1976, but skin and hair samples were only given back in 2002, along with the remains of other unidentified Indigenous people.

The ancestral remains of more than 1,650 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have been returned to Australia in the last 30 years, according Australian Institute of Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) data.

But the Australian government says it is aware of information that there are some 1,500 bodies still held by collecting institutions and private holders in more than 20 countries.

Last year, the remains of 108 people who died more than 40,000 years ago were reburied after they were dug up without permission in the 1960s and 70s.

Not everyone is convinced, however, of the artistic merits of Maynard’s plan.

“I view expression through art as being a core part of being human, but when the public’s money is involved, I think there are fair questions that need to be asked,” Hobart councillor Louise Elliot told the Spectator.

“In this case, how ‘healing’ is an artwork like this? I suspect it is more divisive attention-seeking than truly therapeutic and question-inducing as good art should be.”

But Dr Simon Longstaff from Australia’s The Ethics Centre says Maynard’s conscientious approach contrasts with the colonialists, who “didn’t care about informed consent… any more than they did about taking land”.

“The mere fact of [Maynard] asking the question, and the debate it spurs, is already raising some really interesting questions,” he tells the BBC.

“As a culture, we’ve lost the capacity to deal with genuine complexity, and to recognise that people can have different views on different topics, or different views on the same topics.

“I think the more that art engages us, the better we are as a democracy.”

Maynard’s project stands out in another important aspect, he says.

“There’s lots of mummies in museums and other bits and pieces of people that were collected and commodified in the past,” Dr Longstaff says.

“But where someone has actually, wilfully chosen to [donate their body] as a contribution towards not just art, but social progress, maybe this is the first.”

Maynard says he’s aware of negative reaction, but doesn’t mind if people are offended. “Everyone’s allowed to have opinions. I believe in what I’m doing.

“Unlike the thousands of remains of First Nations people that are displayed around the world that were cut up, dug up and sent without their permission… this person is willingly donating their body.”

The plan is for Relic Act to form part of Hobart’s Current arts festival this November.

Festival sponsor the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) says it’s embracing the work in partial atonement for its own mistreatment of Aboriginal bodies and artefacts.

In a formal apology two years ago, the museum admitted that it had “participated in practices, including the digging up and removal, the collection, and the trade of, ancestral remains of Tasmanian Aboriginal people… largely in the name of racial sciences [which] have long been entirely discredited”.

“While we are aware that Nathan’s proposed work may be confrontational, and that some members of the community may be uncomfortable… we believe it is an important part of our commitment to [our] apology and truth-telling,” the museum’s statement said.

“Once the final shape of the work is clear, TMAG will continue to work to ensure the work complies with all relevant legislative requirements.”

Nathan Maynard says his successful applicant will “understand the history and First Nations struggles”. But what else is he looking for?

“I’m not 100%, but I really, really want to collaborate with this person. I think who they are and their beliefs will really shape this. I want to know if they’re genuine. I want to know that they’re in it for the right reasons.”

Related Topics

-

-

16 July 2020

-

-

-

6 April 2022

-