A cool breeze blows off the West Manila Bay into a grove of mango trees some 100km west of the Philippine capital.

In the sky above, a family of Pacific swallows are busy doing acrobatics. Sitting rather incongruously in this bucolic scene is the vast concrete hulk of the Bataan nuclear power plant.

This is South East Asia’s first nuclear power plant, which was completed in 1986. Except it has never produced a kilowatt of electricity. It was never even put into operation.

Now, more than three decades after it was finished, there is growing support for opening it.

A rising energy bill and the ever-present threat of climate change is once again turning the tide in favour of nuclear power across the world. So why not in the Philippines, a developing economy where electricity is essential but expensive and often dirty?

But the real question is: how easy is it to start up a 38-year-old nuclear power plant that has never been used?

Ambitious or outlandish?

The early morning calm outside the Bataan nuclear power plant is broken by the whop-whop of an approaching helicopter.

Minutes later, Congressman Mark Cojuangco leads the way into the plant. Passing through a semi-lit machinery room, he points to the maze of piping and electrical conduits: “Look at the quality of that wiring. Look how neatly it is laid out.”

He walks down a long corridor, and through an airlock into the main reactor building. The walls are 1.5m-thick concrete; the whole containment structure is lined by a 30mm-thick welded steel liner.

“Please feel the welds,” he says, patting the walls. “I challenge you to find welding as nice as this anywhere in the Philippines. In the US they are required to do X-ray inspection of 20% of the welds [in a nuclear plant]. Here it was 100%, so arguably this building is better quality than in the United States.”

For more than a decade Mr Cojuangco has been waging an uphill battle to open the plant. It is an ambitious, some would even say outlandish, idea.

“I don’t think there’s any way they can get that thing going,” a foreign diplomat said at the mention of the Bataan nuclear plant. “That looks like an accident waiting to happen!” was another response upon seeing a photo of the plant.

So, who would want to take this on? The answer is President Ferdinand Bongbong Marcos Jr.

For President Marcos Jr the plant is unfinished family business. It represents what might have been if his father hadn’t been ousted from power.

In the mid-1970s, with the world’s economy reeling from the 1973 oil price shock, President Ferdinand Marcos Sr decided to bring nuclear power to the Philippines.

It would have put the country alongside Japan and South Korea as a pioneer of nuclear energy in Asia. Marcos Sr commissioned the US company Westinghouse to build two pressurised water reactors on the Bataan peninsula, on the far side of Manila Bay.

By the end of 1985 the first reactor was complete and ready to be loaded with nuclear fuel.

But in February the following year Marcos Sr was forced from power as two million protesters took to the streets of Manila, demanding an end to his dictatorship.

Just eight weeks later reports began to emerge of a terrible accident at a nuclear power plant in the then Soviet Union. A new word entered the global vernacular: Chernobyl.

Plans to load fuel into the Bataan plant were put on hold indefinitely.

Stepping back into the 1970s…

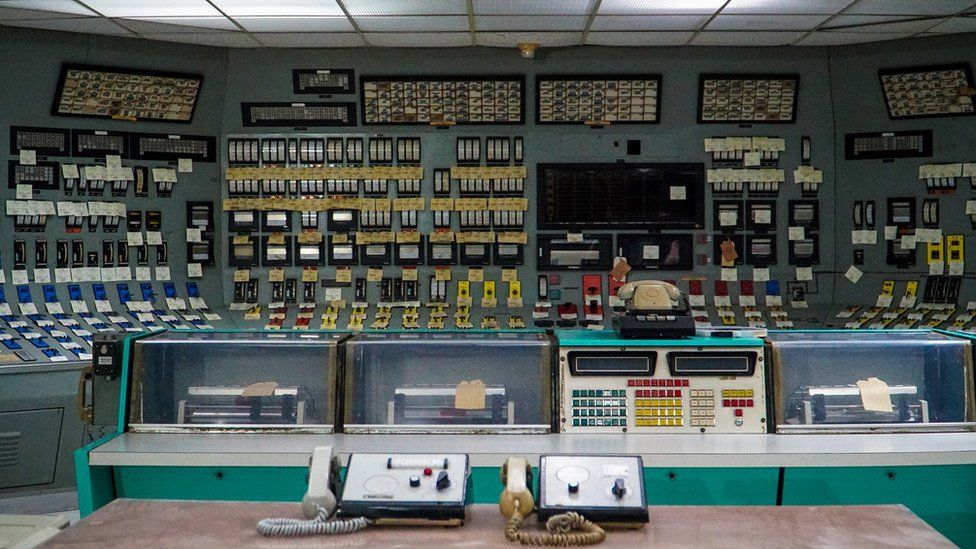

Inside the plant, the main control room looks shockingly old and outdated, almost like a museum.

The wall panels are filled with dozens of ancient-looking analogue dials. Below them, the control panels are a forest of black mechanical switches.

Mr Cojuangco waves away these objections: “People always use the analogy of cars or motorcycles. But the mode of ageing of a nuclear reactor is from neutron bombardment. So far, this reactor has had none, so effectively it’s brand new.”

He doesn’t deny that the systems in the plant will need plenty of work, and that it will cost time and money. He says South Korean nuclear operator KEPCO, which runs an identical nuclear plant in Busan, has offered to bring the one in Bataan up to date for around $1.5bn (£915m).

The plant’s lone reactor – a planned second one was never built – can produce up to 620 megawatts of power, about half the capacity of its more modern counterparts.

Mr Cojuangco repeatedly points out that Bataan would not be the first old, mothballed nuclear plant to be put into operation.

It’s been done before – in Tennessee. Work on Watts Bar Two, as the plant is known, began in 1973, even before Bataan. But then it was mothballed for decades, says Mr Cojuangco, before they decided to finish construction in 2009.

“In 2016, it became America’s newest nuclear plant. If it’s ok there, then why not here?” he asks.

For President Marcos Jr this might well be the best opportunity to revive his father’s dream. The war in Ukraine has set off another energy price shock across the globe, and the Philippines is being hit hard.

At the Philippine Nuclear Research Institute, Dr Carlos Arcilla points to a pie chart that breaks down the country’s energy sources.

“You can see 50% is from coal, and 90% of that coal is imported from Indonesia,” he says.

The Philippines has one small natural gas field of its own, but that is running out. Electricity prices have doubled in the last 12 months as the country becomes more dependent than ever on imported fossil fuel.

“The average Filipino already pays 10% of take-home pay on electricity,” Dr Arcilla says, adding that prices will go higher.

The ‘sleeping monster’

The impact is greatest among the poorest. You don’t have to walk far in Metro Manila to find poor neighbourhoods, or barangay as they are known. All over the city vacant land is taken over and turned into squatter settlements, where homes are made from scrap wood and corrugated iron.

In one barangay not far from Dr Arcilla’s office lives Marilou Calica, a 47-year-old mother of six, who works as a part-time cleaner in a government office. The fatigue is written on her face.

“I haven’t paid my electricity bill for the last three months,” she says. “After I have bought food there is nothing left.”

She pulls out a sheet of printed paper – a final notice from the electricity company. Her outstanding bill: 5,000 pesos (about $100; $75). She says it’s double what she paid a year ago.

“If I don’t pay this week, they will cut me off. I may be forced to go to the money lender.”

Despite the struggles of poor Filipinos, the move to reopen the Bataan plant – and eventually lower the country’s energy bill – faces stiff opposition.

Anti-nuclear groups say re-commissioning the plant will take years and do nothing to help people like Ms Calica. Instead, they say the government should be investing in local solar and wind projects that are cheaper and much quicker to build.

“If they get it running, by 2040 it will contribute only 2.5% of the power in the Philippines, so why do they really want to do it?” says Derek Cabe, who leads the Nuclear Free Bataan Movement.

She says her parents’ generation fought to stop the plant in the 1980s and she is ready to do the same now.

“We cannot let the monster live again,” she says. “We call it the sleeping monster and we cannot let the monster be awakened.”

Those who oppose the plant draw comparisons between the Philippines and Japan, and between the Bataan plant and the one in Fukushima, which was destroyed in the 2011 tsunami.

Both countries sit on the so-called Pacific Ring of Fire. The Philippines has two dozen active volcanoes, and is regularly hit by earthquakes and is also vulnerable to tsunamis.

But Mr Cojuangco, who has been to Fukushima and studied the disaster there, is not worried.

“Before the incident in Fukushima I had no basis for saying that if we had a 9.0 earthquake here, we would sail through it. But now I have the evidence. The plant here is 18 metres above sea level. With a same-sized tsunami as Fukushima the plant would not even get wet. If this plant had been at Fukushima, there would be no incident to talk about.”

Around 60% of Filipinos now say they support the country building nuclear power. And there appears to be no scientific reason to stop this relic from the 1970s from producing electricity one day.

Its biggest obstacle is politics. In the Philippines, a president can only serve a single six-year term. And for Mr Cojuangco the moment is now because after 37 years, history has come full circle.

“In the 1980s we wanted to be independent of fossil fuels,” he says, “Now in 2023 we have an energy crisis again, and there is another Marcos president in the Malacañang palace.”

You might also be interested in:

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Related Topics

-

-

17 January

-