Thutan Chewang, 71, still remembers the day the war began.

It was October 1962 and China had just launched a surprise attack on what was then known as the North East Frontier Agency (which later became Arunachal Pradesh state) in north-eastern India.

“They [Chinese troops] came charging from all sides. People started to flee, fearing for their lives,” says Mr Chewang, who was just 11 at the time.

The attack was swift, and despite putting up stiff resistance in some areas, Indian forces appeared to be struggling against Chinese troops.

Soon, China seized Mr Chewang’s hometown Tawang, a few miles away from the disputed border between the two countries. China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troops remained there for around a month before withdrawing.

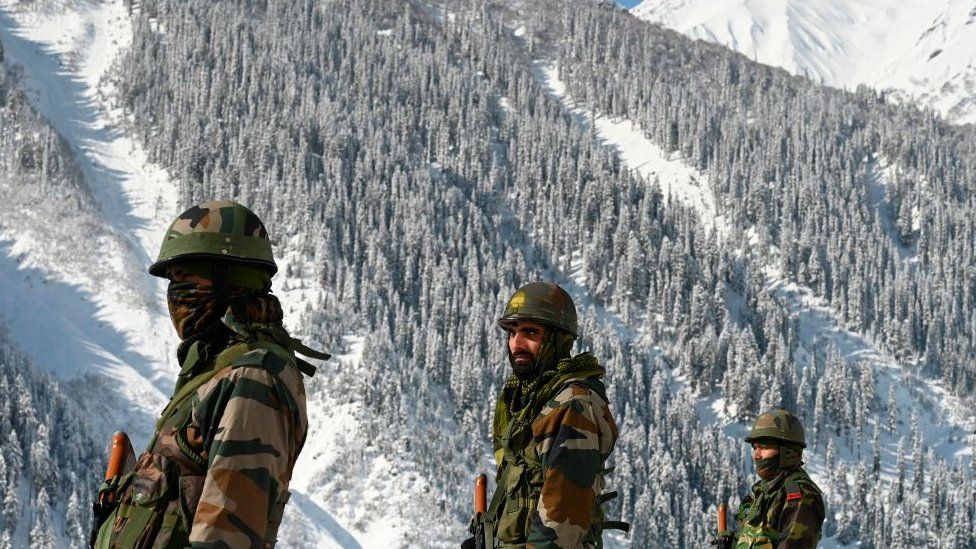

More than 60 years later, that war still casts a shadow over the people of Tawang – especially when tensions escalate between the nuclear-armed neighbours. In December the town was back in the headlines when Indian and Chinese troops clashed along the Tawang border.

But locals say despite the pain of the past, they are looking forward to a more promising future.

“A lot has changed in Tawang between then and now,” Mr Chewang says.

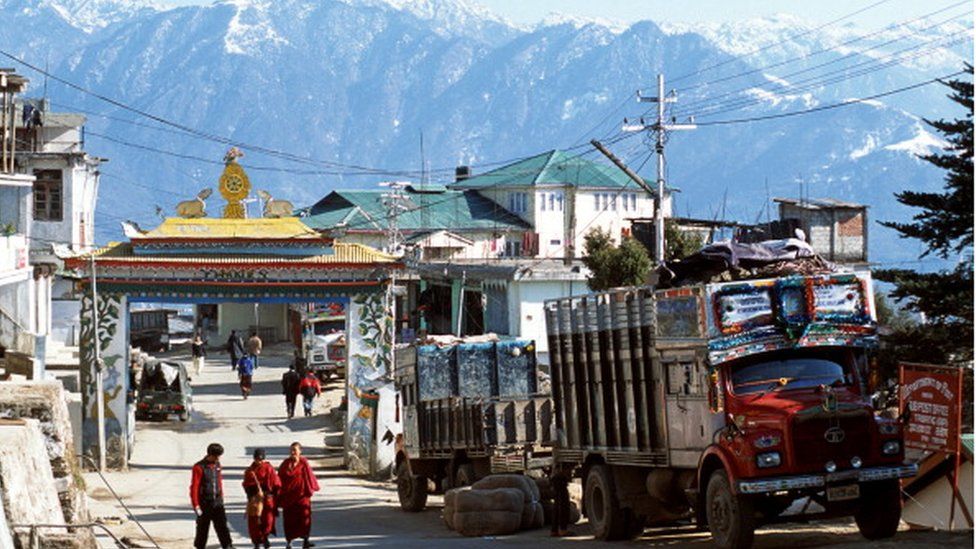

Perched some 3,000m (10,000 feet) above sea level in the westernmost part of Arunachal Pradesh, Tawang shares a boundary with China in the north and Bhutan to the south-west.

At first glance, the town could easily be mistaken for one of several hill stations in India, with mushrooming hotels, eateries and small market areas, and rampant residential and commercial construction.

But there are many things that set it apart. The 8m-high giant Buddha statue looking over the township and the sprawling Tawang monastery – India’s largest Buddhist monastery – underscore the influence and significance of Buddhism here.

Tawang is one of the most important pilgrimage sites for Tibetan Buddhists and attracts a steady stream of tourists every year.

But its strategic location has long made it the focus of tensions between India and China – Tibet, annexed by China in 1950, lies just 35km (22 miles) to the north. In fact, the Tawang monastery was where the 14th Dalai Lama briefly stayed after fleeing from Tibet in 1959.

India and China share a frontier that isn’t fully demarcated – India says it is 3,488km long but China puts it at around 2,000km. Both sides have deployed tens of thousands of soldiers with heavy armaments along of the Line of Actual Control (LAC), which separates Chinese and Indian territory.

China continues to stake claim on the whole of Arunachal Pradesh, calling it “South Tibet”. In 2021, it even came out with a list renaming 15 places in the state, triggering a sharp response from India. Beijing has also routinely objected to visits by the Dalai Lama and Indian leaders to the region.

But many people in Tawang say that they don’t allow the border tensions to dominate their lives. Civic issues feature more frequently in their conversations than China.

“The media blows things out of proportion at times,” says Karmu, who goes by only one name and runs a garment store in Tawang.

The “exaggerated” media coverage of border face-offs, Ms Karmu adds, brings fewer tourists to Tawang, hitting incomes.

While many people from the area join the Indian army, paramilitary forces and other government jobs, others depend mainly on tourism.

The Indian government has now allowed tourists to go right up to the LAC in the Bum La area, opening up another income source for scores of cab operators in Tawang, some of whom undertake multiple trips to the border in a day.

Tenzin Darge, who runs a gift store, says that life in Tawang is as normal as it is anywhere else.

“The media makes a hullabaloo every time something happens on the border. But for us, it is life as normal.”

That doesn’t mean the town has forgotten the horrors of the past.

Sitting in the courtyard of the Khinmey monastery near his house, Mr Chewang speaks of the hardships people had to face during the 1962 war.

“We didn’t even have proper roads. People walked night and day through jungles to reach safer places. It was a nightmare.”

For others, too, the memories of 1962 are still fresh.

Lobsang Tsering, 71, recounts how his parents fled all the way to the neighbouring state of Assam for shelter.

He says it was equally hard to return. When China announced a ceasefire and withdrew its troops in November 1962, many who had escaped from Tawang were too afraid to go back.

“We were told that the war was over and that we could go back but not many could believe or understand this. Some thought that they were going to be handed over to the Chinese,” says Lham Norbu, 76, who, along with his family had also escaped to Assam in 1962.

The journey back home also left many scarred.

Rinchin Dorje, who was in his mid-twenties during the war, says he remembers seeing dead bodies of Indian soldiers on the roads.

“I wish I could forget those memories,” he says.

A memorial at Tawang lists the names of 2,420 Indian soldiers who died in the area during the 1962 war. The bullet-riddled helmets of Indian soldiers displayed there are also a grim reminder.

Others are trying to keep the memories alive in their own ways.

Around 22 miles from Tawang, in a small township called Jang, is a roadside restaurant called Café 62.

Named for the year of the war, the eatery was opened by Rinchin Drema, a retired paramilitary solider who served in the army for 21 years.

“When the war happened, our elders were put through a lot of misery. Café 62 is just a tribute to all they went through,” he says.

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC:

Related Topics

-

-

14 December 2022

-

-

-

13 December 2022

-