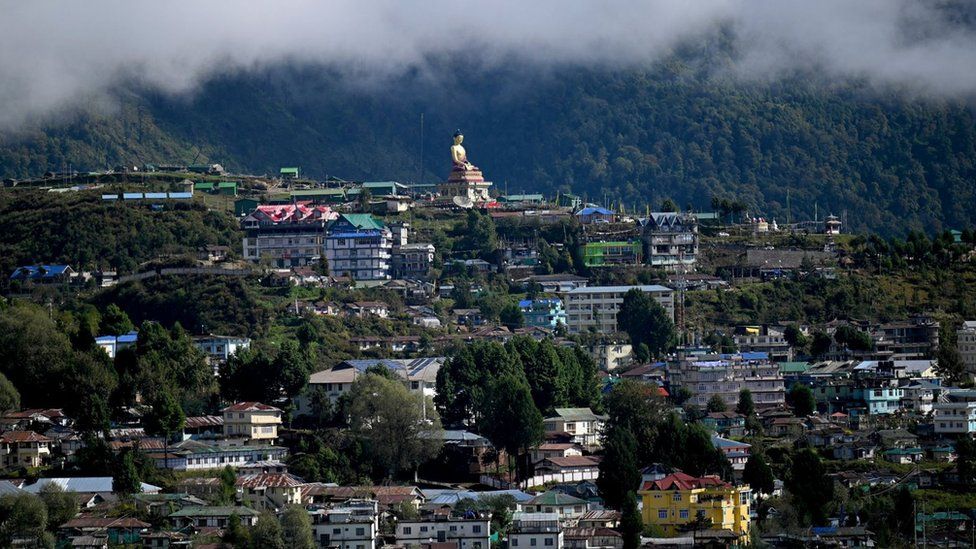

High in the Himalayas, the holy town of Tawang is one of the most intractable issues in the border dispute between India and China – and a potential flashpoint for future conflict.

Along snow-capped ridges to its north, soldiers from Asia’s two biggest armies face off, sometimes just a few hundred metres apart.

Last December, they clashed in what some experts saw as a worrying sign of how things could escalate.

Tawang, a pilgrimage site for Tibetan Buddhists perched some 3,000m (10,000ft) above sea level, is home to India’s largest Buddhist monastery.

For this reason and because of its strategic location, it’s long been the focus of tensions between the nuclear-armed neighbours.

The town is claimed by China. Tibet, annexed by China in 1950, lies just 35km (22 miles) to the north.

“It’s not just the Tawang sector,” Zhou Bo, a retired senior colonel in the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, told the BBC.

“The entire Arunachal Pradesh [state], which we call southern Tibet, has been illegally occupied by India – it’s non-negotiable.”

Tawang hit the headlines in December after the first clashes there in years. India said Chinese soldiers encroached into its territory and “unilaterally tried to change the status quo”.

China said its troops were on routine patrol on their side of the Line of Actual Control (LAC), which separates Chinese and Indian held territory, and had been “blocked by the Indian army illegally crossing the line”.

The fight that ensued reportedly left several soldiers injured on both sides. It followed a far more serious clash in 2020 at the other end of the disputed frontier.

In a mass brawl in Ladakh’s Galwan valley, 20 Indian soldiers and four Chinese troops were killed – it was the first fatal confrontation over the border in 45 years and highlighted the risks faced as the rivals try to further their strategic goals.

Since then, tensions have escalated, with both sides deploying tens of thousands of troops with heavy armaments along the disputed border.

Claims are being reinforced in other ways too.

In mid-February India announced plans to invest in more than 660 “vibrant villages” to encourage locals near the border to stay. The move was seen as a response to reports of model villages on China’s side.

India is also promoting tourism in Arunachal Pradesh with hotels, restaurants and home-stays springing up in Tawang and surrounding areas.

India and China share a frontier that isn’t fully demarcated, and have overlapping territorial claims. India says it is 3,488km long; China puts it at around 2,000km.

Of all the disputed areas, Tawang remains high up on China’s list of claims.

It was among areas taken during a brief war in 1962 that ended in a humiliating defeat for India. Thousands of PLA troops overran Indian positions before withdrawing.

“Tawang is indispensable to China. The Tibetan spiritual leader the sixth Dalai Lama was born there [in the 17th Century],” said Mr Zhou, who attended India-China border talks as a military expert in the mid-1990s.

“What better evidence do you need to prove that it’s Chinese territory?”

India asserts its boundary claim based on the 1914 McMahon line, named after the British foreign secretary of colonial India.

China refuses to accept the line – it runs from the east of Bhutan across the Himalayas and puts the whole of Arunachal Pradesh on the Indian side.

For China, Tawang offers an entry point to Arunachal Pradesh and the rest of India’s north-east.

Some experts think Beijing wants to bring Buddhist holy sites, like Tawang, under its control to cement its authority over Tibet. When the current Dalai Lama fled to India in 1959, he reached Tawang first after crossing mountains by foot.

There’s also suspicion among some Chinese observers that given the ethnic link between the cross-border communities, Tawang could be used to whip up any future Tibetan uprising.

China’s claims to Arunachal Pradesh have become more assertive over the past 20 years, but it appears it’s been willing to trade.

Liu Zongyi, a senior fellow at the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, says Tawang was central to a deal China offered India during talks in 2006.

“On the premise of recovering Tawang, China was willing to give up its claim for sovereignty over most parts of southern Tibet [Arunachal Pradesh]… in exchange for India’s recognition of China’s sovereignty and control over Aksai Chin,” Mr Liu told the BBC.

He said the offer didn’t succeed because India hadn’t been willing to give up its interests in the east, especially over Tawang, and was also not ready to make concessions on Aksai Chin – currently under Chinese control.

Shyam Saran, India’s foreign secretary at that time, said he didn’t remember any such proposal.

“We never got down to any bargaining on how much territory you are willing to give up, how much territory we are willing to trade off. That stage never came up,” Mr Saran said.

Border negotiations have continued in the years since, but made no progress. The two sides met in Beijing in February for their first in-person talks in three years.

India’s official position remains maintaining the status quo until a final settlement, but Chinese observers are wary.

Mr Zhou, the former PLA officer, says Indian intransigence has generated suspicion.

“In China there are some people who say the Indian attitude is like – mine is mine and yours is also mine. They believe that as India is in control of the eastern sector, therefore they are trying their best to grab more land in the west in Ladakh,” Mr Zhou said.

According to Mr Liu, India has over decades adopted an “offensive defence policy, constantly encroaching on Chinese territory across the LAC and occupying the military commanding heights in the border areas”.

Such remarks mirror criticisms of China’s approach to territory that India regards as its own. “The Chinese keep moving the goal posts or shifting their position,” says Mr Saran.

With both sides showing little flexibility, Mr Zhou thinks resolving the border dispute should be left to the future.

But many in India feel a delay could only be advantageous to China, which has vastly increased its military and economic might in the last few decades.

“As the power asymmetry between the two sides keeps growing, I think we should expect a much more assertive China,” said Mr Saran.

No one expects a war to break out anytime soon, given how much India and China value their strong trade relations. But neither shows any sign of compromise.

As both sides vie for control on the ground, clashes like the recent one near Tawang only become more likely – all it would need is a spark for things to flare up.

You may also be interested in:

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Related Topics

-

-

14 December 2022

-

-

-

26 April 2019

-

-

-

17 June 2020

-