The Afghan Taliban’s apparent decision to allow women and girls a right to go to school and work is a positive development. But it should be welcomed cautiously by the international community until there is evidence of meaningful change. After all, the Taliban have made such promises before.

Taliban officials announced this week that under Islamic law, women and girls have the right to education, work and entrepreneurship. However, there was a caveat, with officials adding that the movement is working to create a “safe environment” for women and girls in schools and the workplace. What this means is unclear.

In a full statement, the spokesman for the Afghan Ministry of Vice and Virtue, Sadeq Akif Muhajir, said that “Islam has given women the right to education, Islam has given women the right to work, Islam has given women the right to entrepreneurship.”

We have heard similar proclamations before. In August 2021, after the fall of Kabul, the Taliban vowed to respect women’s rights in an attempt to portray themselves as more moderate.

In March this year, the Ministry of Education announced that girls would return to secondary school, before quickly backpedaling, claiming that it would need to be in accordance with Islamic law. The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights called this “deeply damaging for Afghanistan.”

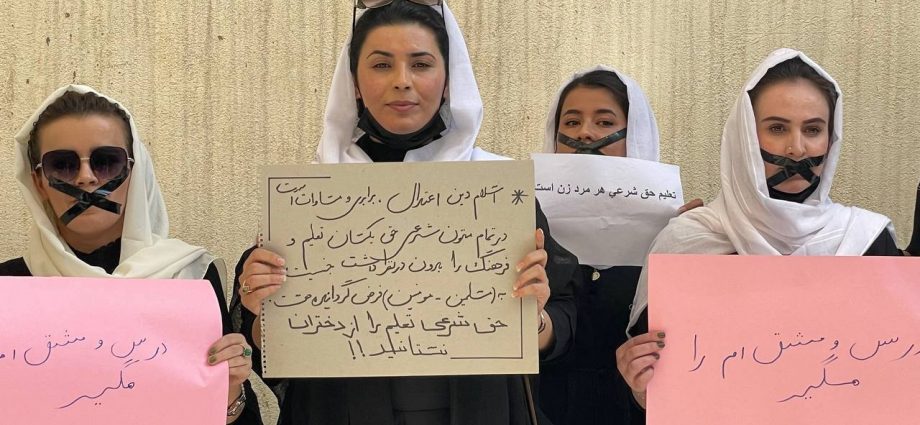

The return of the Taliban has so far had a devastating impact on the lives and rights of women in Afghanistan. Despite calls from the international community to uphold their rights, females have been banned from secondary and university education, forced to wear the niqab and only travel with male relatives, and either forbidden to work, have their jobs taken by men or forced to work in segregated workplaces.

Removing the right of women and girls to work and educate themselves has coincided with a dire economic and humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan.

The withdrawal of international donor funding and the freezing of billions of dollars in Afghan assets by Western banks has caused the economy to collapse, leading to food shortages and mass unemployment.

The United Nations Development Program has warned that the country is facing “universal poverty,” with 97% of Afghans now living below the poverty line and suffering from emergency levels of food insecurity. This has led to malnutrition and the collapse of the health-care system.

The dramatic fall in employment for women has had severe consequences, with families who were reliant on the wages of women now forced into poverty and facing starvation. There have been reports that families have resorted to child marriage for girls so they can afford food.

The intersection between the restrictions on women’s rights and the humanitarian crisis has therefore left women and girls with no opportunity to educate themselves, provide for their families or lead lives of ambition.

So while the Taliban’s recent statement offers a glimmer of hope, the devil is in the details.

Sadeq Akif Muhajir uttering the phrase “If Islam has allowed it, who am I to ban it” is an important one.

The Taliban’s acceptance that a woman’s right to education and employment is allowed under their strict interpretation of Islamic law is an important pivot, considering the movement has previously used Islamic law as a reason to deny women’s rights.

This could reveal that, because of the country’s economic woes and humanitarian needs, the Taliban is finally bowing to the international community’s demands to respect the rights of women. Doing so would increase the chances of official recognition as the government of Afghanistan and result in the inflow of much0needed funds to run the country.

The Taliban may also have begun to understand that the return of women to the workplace would be beneficial for the Afghan economy and greatly reduce the effects of the humanitarian crisis. A better-educated population, with girls returning to school and university, would benefit the country in the long term.

Therefore, an optimist would suggest that the Taliban have decided pragmatically to put their economic and political interests ahead of their strict interpretation of Islam.

But a cynical view would be that this is yet another, soon to be aborted, attempt to look progressive on women’s rights while nothing substantial changes at ground level.

Whatever the reasoning, considering the Taliban’s poor history on women’s rights, the international community should continue to remind the regime that international recognition and the availability of frozen assets will only eventuate when there is meaningful change on this issue.

Doing so may well see an Afghanistan where women and girls are again free to enjoy their rights and pursue their ambitions.