How India-Canada ties descended into a public feud

shabby pictures

shabby picturesYears of close ties between Canada and India, two important strategic partners on business and surveillance, could be derailed by the escalating dispute over the death of a Sikh secessionist head.

India reacted angrily, saying it” completely rejected” the accusations and referred to them as” absurd.” Both have expelled one of the other’s ambassadors, so it is unclear how they will then retreat from the danger.

The nations were making headway toward signing a free trade agreement that had been in the works for some time only recently. Now that negotiations have been put on hold, Canada’s upcoming industry mission to India has been postponed.

How did things get to this place, then?

There was no cutting of terms after the two frontrunners met. According to Mr. Trudeau, Canada will often uphold” freedom of expression” while waging war on anger.

The allusion is made in reference to calls for Khalistan, or a separate country for Sikhs, made by hindu activists in Canada. Millions of Indians experience painful memories as a result of this need, particularly in northern Punjab position, where Sikhs make up the majority of the populace( outside of Punjab, Canada has the highest concentration of SKSs in the world ).

In India, the need for Khalistan reached its peak in the 1980s when a forcible military uprising was put down, killing thousands of people. The activity is no longer well-known in Punjab, and all major American political parties outspokenly oppose it.

However, some members of the Sikh community in nations like Canada, Australia, and the UK are also vocal in their names for Khalistan. Delhi has reacted angrily to Hindu activists’ presentations for and polls on Khalistan in these nations, which are not prohibited it but are a major source of annoyance for India.

Three pro-Khalistan activists passed away in rapid succession in various countries earlier this year, drawing more attention to the issue on a global scale.

Paramjit Singh Panjwar, the commander of the Khalistan Commando Force who India designated a criminal, was shot dead in Pakistan in May; his assailants have not yet been identified.

Nijjar was shot dead outside a Sikh temple in British Columbia three days after he passed away; this crime has now prompted Canada to take an outspoken stance against an influential ally.

They belong to the G20’s top 20 markets and are both Commonwealth nations. Canada sees India as a counterbalance to China and wants to expand its influence in Asia.

When Canada’s Foreign Minister Mélanie Joly visited Delhi in January, she made a reference to the Indo-Pacific strategy report of her nation, which made clear links to Chinese” aggressive” measures in the area. In the shared statement, Delhi did not mention any pro-Khalistan organizations.

The nations have solid trade ties in addition to politics.

With bilateral trade in goods reaching$ 11.9 billion in 2022, up 56 % from the previous year, India was Canada’s tenth-largest trading partner. Additionally, they came very close to signing the deal arrangement that has since been put on hold.

Therefore, there is undoubtedly a lot at stake for both nations.

” I do believe that this serves as a lesson to us all that India’s near ties to American partners are not sacred. This is a wake-up contact that India, while not an aligned person, values its ties to the Global South and, most definitely, its relations with the West. However, Michael Kugelman, chairman of the South Asia Institute at the Wilson Center think-tank in Washington, asserts that this does not imply that it will be shielded from the possibility of a significant problems in connections.

S Jaishankar, the foreign minister of India, stated earlier this year that” vote bank compulsion”— a reference to the support Mr. Trudeau’s Liberal Party receives from Sikhs — has been the driving force behind the Canadian response to Khalistan. The New Democratic Party ( NDP ), which is led by Jagmeet Singh, a Sikh himself, also supports Mr. Trudeau’s minority government.

Some Indian experts concur with this assessment.

The Kalinga Institute of Indo-Pacific Studies’ father, Chintamani Mahapatra, claims that Mr. Trudeau’s remarks on the Khalistan problem are” contentious.”

He” ignores the sentiments of the larger Indo-Canadian community, which includes the Canadian Sikhs ,” and seems to be biased against the Khalistanis. Had he prefer that Quebec separatists receive outside help? Of course not ,” he responds, adding that Mr. Trudeau has made the tension between India and Canada worse.

” Canada does not jeopardize its relations with other nations in the name of democracy, human rights, and freedom of speech.”

However, Avinash Paliwal, a professor of politics and international studies at SOAS University of London, asserts that the rapid escalation might not be the result of purely domestic pressures.

He adds that it’s possible that Mr. Trudeau first tried to bring up the issue through different programs.” If your intelligence organizations have gathered credible information that another country, even if it is an ally, was involved in a secret operation on your land, you’re bound to act on that.”

Another home politicians, including Pierre Poilievre, the main opposition leader, have backed the Canadian prime minister. The US and the UK have both responded, with the US stating that they are” deeply concerned” by the allegations and” in close touch” with Canada regarding the matter.

Experts claim that while Western nations view India as essential to thwart China’s effect, there is also growing concern about the way Mr. Modi is taking Indian politics. Critics claim attacks on minorities have increased since his administration took office, among other human rights issues.

Beijing and Moscow, which are happy to see a” cleft between India and the West ,” will also closely monitor the improvements, according to Mr. Paliwal. He does, however, add that this would not” derail the strategic story” or” force Washington to ignore India.”

According to Mr. Kugelman, China and Russia may view the conflict separately.

Beijing does not want to see India develop closer ties with like-minded nations that are eager to retaliate against China. Therefore, this could be seen as a strategic advantage for Beijing in that respect. He claims that Russia might be perfectly content to see Canada sunk in this issue.

However, a conflict between India and Canada will include political repercussions in the near future. Canada may pose a unique challenge to European governments, particularly the UK and Australia, if it keeps making vehement comments and then accuses India immediately.

But if it gets to the point where they have to decide between India and Canada, it will be a proper pain for them. The UK, the US, and Australia have all made determined claims thus much.

Is India and Canada, however, still resolve their differences to prevent a political conflict for the West?

While the Khalistan problem may have an immediate impact on economic cooperation, according to Mr. Mahapatra, it is unlikely to end long-term relationships between the nations. Additionally, he advises against” extreme measures ,” particularly from Canada.

You don’t need a speech if you’re extending an invitation to the diplomat. He claims that instead of fight, like issues should be resolved through speech and diplomacy.

Related Subjects

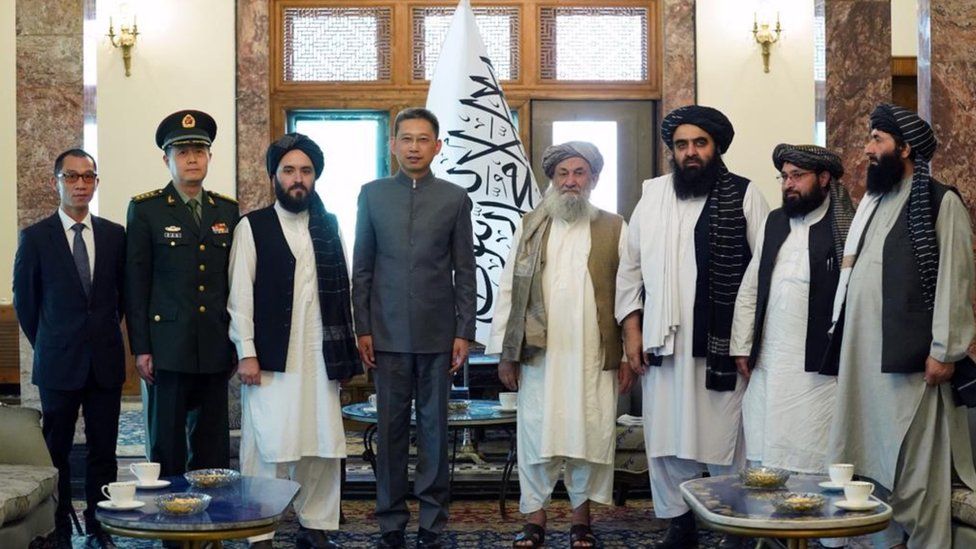

Afghanistan: Taliban welcome first Chinese ambassador since takeover

Business OF TALIBAN MEDIA

Business OF TALIBAN MEDIASince the Taliban took control of Afghanistan in 2021, China has been the first nation to appoint an adviser.

According to the Taliban, Zhao Xing’s session is a sign for another countries to form relationships with its state.

According to researchers, the action demonstrates China’s efforts to increase its impact in the area.

On Wednesday, Mr. Zhao was welcomed by Taliban officials at the national palace in Kabul as part of a formal process.

According to China’s foreign ministry, Beijing will” continue advancing dialogue and cooperation” with Afghanistan and has a” clear and consistent” foreign policy.

It continues by saying that Mr. Zhao’s appointment is a” standard rotation” of Chinese diplomats to Afghanistan.

China was one of the first nations to join with the Taliban since US-led international forces withdrew from Afghanistan in August 2021, despite the fact that no foreign government has publicly recognized them.

Being in the middle of a place crucial to Beijing’s Belt and Road system initiative, the nation holds significant interests for Beijing.

According to some experts, China’s action is intended to increase its impact in the area.

According to Farwa Aamer, Director of South Asia Initiatives at the Asia Society Policy Institute,” China aims to position itself as an important player in the region by being the first to name an embassy post-takeover. This may be a political stretching of muscle, especially when some European countries are still hesitant to engage with the Taliban.”

She continued,” Maintening diplomatic ties with the Taliban may also help China keep its security concerns under control.”

According to reports, acting foreign secretary Amir Khan Muttaqi and acting prime secretary Mohammad Hassan Akhund will meet with Mr. Zhao at the presidential palace.

Wang Yu, China’s past ambassador to Afghanistan, was fired by Mr. Zhao next month.

The Taliban administration has come under fire for violating human rights in Afghanistan. Particularly, it is believed that the reduction of women’s rights under their law is among the harshest in the entire world.

Related Subjects

On this account, more

Exclusive interview with Paul Yang, BNP Paribas CEO for Asia Pacific | FinanceAsia

Paris-headquartered BNP Paribas boasts a history of over 160 years in Asia and today, it draws upon a 20,000-strong team that is active in thirteen markets across the continent.

The regional effort is led by Paul Yang, who ascended to role of CEO for Asia Pacific in December 2020, as the world succumbed to the full throes of the beginnings of a three-year pandemic. As society grappled with widespread affliction, Asia’s key economies responded to rapidly evolving government direction with fervour: leaving borders closed and markets shaken.

However, as you will discover through this exclusive interview, Yang was defiant in his refusal to be beset by external challenges. Proving himself an astute leader at the regional helm, he navigated the uncertain scenario deftly, and would go on to secure solid returns for both full-year 2021 and 2022; as well as robust revenue for the first quarter of 2023.

With a view to steering the bank’s business in support of the group’s Growth, Technology and Sustainability (GTS) strategy for 2025, FinanceAsia sought Yang’s take on Asia as a key international powerhouse, and learned about the milestones of his international career to date.

|

Entering Asia BNP Paribas’ forerunner, the Comptoir National d’Escompte de Paris (CNEP), was set up by France’s finance minister following the hardships endured during the French Revolution; to curb mass bankruptcy in the financial markets; and to stimulate the economy. Following signature of a free trade agreement with the British, the Comptoir sought to develop an international strategy to source the raw materials required to support the flourishment of European industry. To do so, it extended beyond its French national borders for the first time; establishing offices in Calcutta and Shanghai in 1860, independent of foreign partnership. Later, CNEP merged with the Banque Nationale pour le commerce et l’industrie (BNCI) to form the Banque Nationale de Paris (BNP). Capitalising on these regional capabilities, the bank made Hong Kong the centre of its Asian platform. |

Q: Paul, you’ve been based in Asia Pacific for the majority of your career with BNP Paribas. Can you share what has defined BNP’s corporate journey in Asia so far?

A: Well, I wasn’t there in the 1860s, but it’s true that we have had a very long presence in the region. However, I consider “modern” BNP’s presence to be quite recent. It was really the bank’s merger in 2000 that created who we are today, elevating us as France – and then Europe’s – leading financial group and the most profitable bank in the eurozone.

But regarding Asia, we’re proud to be able to say that we’ve been here for a long time, which demonstrates our commitment to the region.

In Hong Kong, for instance, we often deal with multiple family generations of entrepreneurs and tycoons. The same is the case for some of our mid-cap clients – we have dealt with their fathers. We have built a sufficient network in the region to be able to play a key role in executing succession plans and building businesses for the future. It really means something that we’ve been here for so long and to be profitable in all of the 13 markets where we operate.

These days, being relevant to your clients counts. You need a strong balance sheet, presence and scale to guide key them from their home markets into new areas. This is how we started, building our financial institutions group (FIG), then multinational and corporate (MNC) franchises,before further progressing to build scale, solutions, products and platforms.

We have developed a strong Asian presence and over the last three years, we’ve built on connectivity to improve the flows between the various corridors we participate in. We are relevant to key local participants and accompany international clients in reverse, also.

This goes for all facets of our business: whether in the corporate and institutional world, or in consumer finance. We are bigger than the sum of our parts and many things we do have relevant purpose for our clients.

Q: How does the bank’s business in Asia compare to that of the European markets (e.g. France, Italy, Belgium and Luxembourg)?

A: Understandably, our stronghold is Europe and we are significant as well in America. But overall, Asia represents a sizable portion of group business.

The bank’s longevity and strong heritage in Asia Pacific, coupled with our integrated business model places us in good stead to extend and reinforce our presence in this growth region.

In this regard, BNP Paribas’ Asia Pacific revenue contribution to the group’s corporate and institutional business is about 20%; and it will continue to grow.

Ultimately, the bank is emerging as a leading player in the region – and this brings us to a better position to aim for larger deals and more ambitious goals.

In this respect, we have grown our market share in our regions – for example, we hold dominance in markets such as Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong in the wealth management space, and we have recently launched an onshore wealth capability in Thailand. Asset management is developing; and our insurance business – Compagnie d’Assurance et d’Investissement de France (Cardif), has also been successful.

Where we do not have underlying domestic market strength, we choose to partner. We are humble enough to realise that sometimes it is better to do so. For example, in Asia, on the insurance side of the business we have partnered with local banking distributors. We started exploring this type of partnership around 25 years ago in markets such as Taiwan, Japan and Korea, and we are building up our strength in China, India and Southeast Asia.

The same goes for the retail side – personal finance. In 2005, we became a strategic shareholder of Bank of Nanjing in China and we are now their single largest shareholder with a 15.7% stake.

We have built core business through partnerships, but where we think that we can control the entire business because it’s part of our DNA, is on the wealth management and corporate institutional banking (CIB) sides.

Q: What are the bank’s strategic priorities across Asia over the short and long term?

A: We are a bank that tries to deliver short-term results alongside long-term goals. Long-term relationships are part of our nature from a strategy perspective, and we are not in the business of pursuing rash opportunities when things look great and then making drastic cuts in a down cycle. We have a long-term vision and try to cultivate trust and relationships with this timeframe in mind.

From a short-term perspective, we have targets around our top line to maintain cost discipline and ensure that we invest for the future. We are intrinsically risk-aware and we insist on having a good mix of new blood and older experience, to move forward prudently.

Diversification is key. When you pursue disciplined growth, you avoid temptation, fashion and fad and consequentially, mistakes. Across all markets and products, we want to be positioned as the number one European bank for CIB, the preferred partner for wealth management, insurance and asset management – and we are not far from achieving this goal.

Asia comprises a mix of developed and developing markets. Whether you look at the position we have in Japan, Australia, or Korea – or across more emerging business hubs such as Southeast Asia or China, we are well positioned there for our clients and we generate good returns.

Some of our peers will concentrate their presence at a particular local base, say in hubs. But we do not believe in guaranteeing strong, underlying growth simply by sitting in Hong Kong and Singapore and flying bankers all over the place.

The creation of local platforms is important. We have been building these in a considered manner across Southeast Asia, Taiwan, mainland China and elsewhere for the past decade and we are able to see the results. For example, we recently complemented our business mix with a securities licence in China. Once we have completed the takeover of several prime brokerage businesses from our competitors, we will see an increase in the equity cash portion of our business mix. Then there’s the joint venture (JV) we secured with the Agricultural Bank of China, which is the largest bank in the market by network and with whom we’ll be structuring investment products for retail clients.

Q: Diversification is a theme that has emerged from the pandemic to build business resilience. But are there any particular geographies or sectors that stand out as offering growth opportunity?

A: We’ve seen some volatility in the banking sector, but as a group, our corporate culture has focussed on development in a very diversified way. In terms of resilience, this sets us apart.

If you look at our group results, you will see that around 50% of our business is in the domestic retail and consumer finance market;

a third is in CIB; and over 15% is concentrated on activities such as asset gathering – from private banking to asset management and insurance. Within CIB, there’s also security services, which might not have a great cost income, but involves limited capital consumption and brings recurrent fees.

This percentage mix has been kept stable as we’ve grown across all areas and however you slice and dice our business, you will always see diversification. It’s the same for our client base – we not only serve financial institution clients but also corporates and high net worth individuals (HNWI). These three pillars are quite well balanced and offer us the means to build a sufficient product platform.

Capital market activities, including equity capital markets (ECM), debt capital markets (DCM), fundraising and advisory services can be volatile and event-driven; while another big portion of our business and effort is in transaction banking: following the flow of finance, supply chains, trade finance and cash management activities.

The interest rate surge of the last 12 -18 months has been very much beneficial to the cash management business, while monoliners who rely only on investment banking, have suffered. We have benefitted. Whatever way the world or region goes, we are naturally hedged.

Across the Asian region, our presence differentiates us from the rest. We are more than 2,500 in Hong Kong, have 2,200 in Singapore, plus a solid foothold in Japan where we’ve ranked consistently within the top five thanks to our leadership in the global macro environment, both in fixed income currencies and commodities (FICC) and across equity and credit.

In Australia, we have a dominant position in the custodian business that we started 20 years ago; we do well in China, and then we have strong ambition in India and Southeast Asia. I cannot see any market where there isn’t potential.

Q: How do you aim to grow the Asian business?

A: In the past, we have grown organically – even when we looked to secure Deutsche Bank’s prime brokerage business in 2019, it was not a typical acquisition. They were trying to expand in terms of platforms and wanted to lighten up their equity business. Meanwhile, in July 2021, we acquired another 51% of Exane, the top-rated equity research business, following a successful 17-year partnership where we had held 49%.

Both deals demonstrated ambition and keenness to complement the building blocks of our equity business.

So yes, our focus is organic over external growth. We feel it’s better to rely on organic opportunity.

Q: Which developments excite you across sustainability?

A: We’ve been involved in sustainability for over a decade, having started our sustainable finance forum (SFF) in Singapore seven years ago. I’m happy to see that what was a niche market is now very much mainstream.

I would say we have been dominating the ESG thematic, especially when it comes to corporate social responsibility (CSR). We’ve exited from carbon-heavy energy, have moved towards renewables, and we are working to lighten up our upstream exposure. It’s pleasing that every year we do more, whether green bonds, sustainable loans or other structures. We are among the top three banks in the space and even if we cannot manage to stay number one, our efforts make a positive impact across society.

Last year, we created a group of more than 150 bankers, the Low Carbon Transition Group (LCTG), to support our clients’ energy transitions. We’re experienced, so are not having to start from scratch and can support those corporates who might not know where to begin.

We recently held an electric vehicle (EV) conference where we gathered more than 300 clients, corporates and investors in Hong Kong. The topic sits well with what we want to do in the sector around mobility as an engine for growth and we think we can bring value-add to our clients.

EV adoption figures are impressive. In 2019, they accounted for 2.2% of the global total in cars sold, and rose to 13% last year. In China, the penetration figures are double. We’ve seen how this market can surprise everybody regarding adoption of new technologies. China did it with internet access, the smartphone, payments, and now EV. It’s exciting.

Q: You started in the IT department, held positions in Paris, Taipei and Hong Kong, before taking on Asia Pacific leadership at the height of the pandemic. What has shaped your career?

A: You’re right, I took the helm of the region in the middle of the pandemic. I was very fortunate to have been based in Asia for more than 20 years, so I knew the people, the teams, key clients and our platforms, which helped tremendously. During the pandemic, we adopted new technologies and forms of digital communication to stay close to our clients. We succeeded and the vast majority of our clients did also.

I think I’ve been lucky. I started in IT – I’m not sure I was good enough to stay in it, but my first business trip was to Hong Kong. I loved the place and dreamed of how amazing it would be to be based there. Thirty years later, here I am.

Like everybody, I’ve worked hard, but I was very fortunate, and at times, daring. When I wanted to switch from IT to credit, people said “No, Paul. We like you very much, but please don’t do something stupid. You already have a promising future.”

My response was to ask for a chance. I was curious to learn and probably would have gone elsewhere if I hadn’t been given opportunity. Fear around not succeeding makes you try harder and you don’t want to disappoint the people who see something in you.

A few years in, I moved from credit to corporate banking, where I was offered a great job in China – everybody wanted to be in China, but interestingly, it was a bit early – nobody was ready to do much there. So, I transferred to Taiwan to lead the corporate banking team and learned management on the ground. Doing quite well, I was later promoted to head of the territory and then after, moved to Hong Kong. That was 18 years ago!

For me, it’s been a combination of hard work, opportunity, luck and meeting the right senior people to support my development.

One memory that stands out was when the bank appointed a Hong Kong local to lead Greater China. It was a big move, as previously, the standard was someone French and male, but a Hong Kong woman took on the role and I worked for her for many years, learning from her insights. She believed in me and offered me the support to grow.

Q: What’s been the biggest highlight of your career to date?

A: This is difficult! But a key milestone was being given the opportunity to move from IT to banking. I’ve always liked a challenge – from coding, to implementing new tech systems and platforms, to what I do today.

I’ve seen many different things in my career and I have always been very curious. I’ve really cherished every opportunity I’ve had.

I’ve been very happy in the organisation and even today, it’s meaningful to partner with faces old and new. Back in 2004-2005, I had the opportunity to build a partnership in China. After much research, we invested in the Bank of Nanjing, which, two years later, was the first City Commercial Bank to list. There are many board members who I know well. It’s great for both them and me – it’s nice that our professional focus involves making core connections. It’s meaningful.

Q : If you weren’t in banking, what do you think you’d be doing?

A : Very early on, I think we all wanted to be football players! For France or Argentina – the recent World Cup rivals!

Sometimes I reflect and think I would have been pretty good at teaching. But whatever alternate path I would have taken, it would have involved international opportunity.

I grew up first in Taiwan before moving to France and it was at that point that I knew that I wanted to see the world and find opportunity to do so.

Of course, these days, when I look at my daughter evolving, I can see that there is a lot of opportunity ahead for her, more so than when I was young.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.

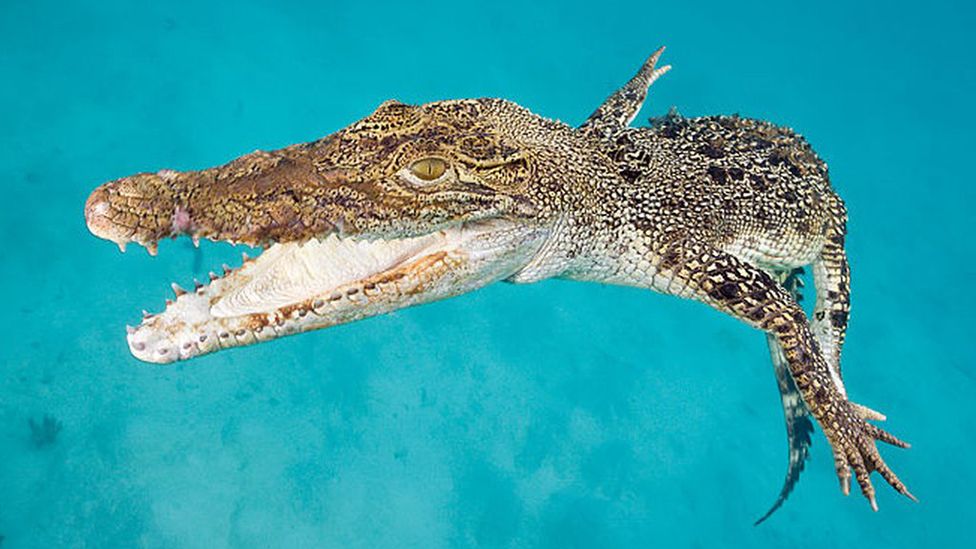

Dozens of crocodiles in China escape during floods

shabby pictures

shabby picturesAccording to Chinese authorities, Typhoon Haikui-related flooding has caused dozens of crocodiles to flee a mating land in southwestern China.

When a river in Maoming, Guangdong state overflowed, about 75 crocodiles fled in its direction.

Local government shot or electrocuted people” for health reasons ,” while some were recaptured.

Eight snakes have been rounded up thus far, according to Chinese state media, leaving heaps at large.

Local people have been instructed to stay at home.

For more than a year, Typhoon Haikui has been wreaking havoc on China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Japan in southern Asia.

Following the storms, which has since been downgraded to a tropical storm and has resulted in landslides and flooding, seven people have died and three more are still missing in southwestern China.

According to Maoming’s Emergency Management Bureau, 69 people and 6 young turtles managed to flee after the storms.

Although there have been no reported fatalities, authorities acknowledged that some of the reptiles are still in deep waters. Sonar technology has been used by emergency service to locate them.

A staff member at the state’s emergency bureau said,” It is now under command, but the number of alligators that escaped is a bit higher.”

According to one fire, the majority of the captured turtles have been shot to death.

According to the Washington Post, they are Japanese crocodiles. According to Crocodiles of the World, a UK park, these are fresh reptiles that can grow to be 3 meters or almost 10 feet long.

The child alligators that have been captured weigh on average about 75 kg and are longer than 2 meters, according to the fire.

Numerous reptile farms can be found in Maoming, Guangdong province. In addition to being raised for beef, they are bred for their body.

You might also get curious about:

This film is incompatible with playback.

JavaScript must be enabled in your website in order to enjoy this video.

Related Subjects

On this account, more

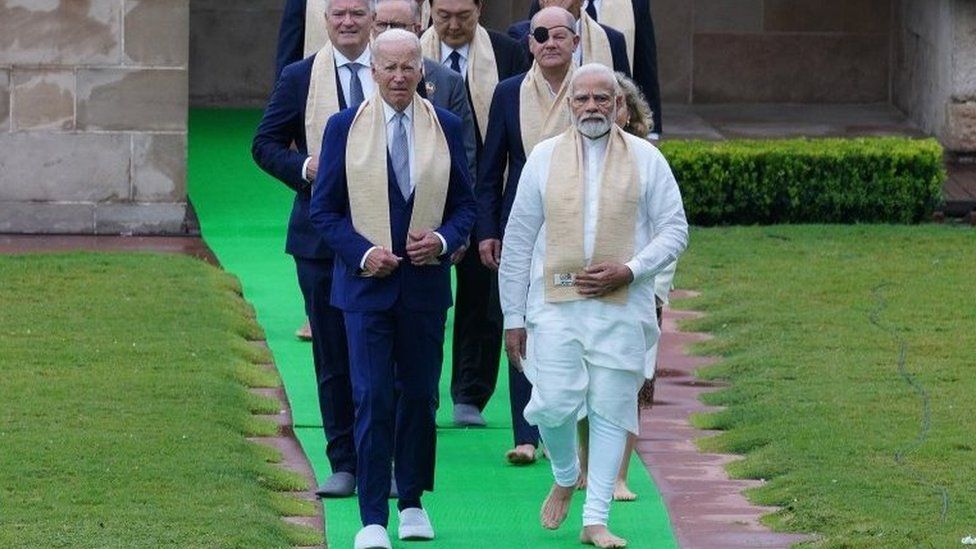

How India overcame bitter G20 divisions over Ukraine

AFP

AFPIndia has achieved significant diplomatic success thanks to the G20 mutual resolve in Delhi.

Given how polarized the party was over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, coming to an agreement on a joint statement appeared to be nearly impossible just days ago.

In the end, we had a resolve with no dissenting remarks and unanimous support from all G20 members.

Although important people, such as the US, the UK, Russia, and China, praised the result, Ukraine itself, which was not represented at the summit, was angry.

So how did India manage to unite countries with such diametrically opposed perspectives on Ukraine?

Some hints can be found in a careful reading of the announcement and some political developments that occurred just before the summit.

During its quarterly conference in August, the five-nation Brics class, which includes Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, decided to add six new people.

Argentina, Ethiopia, Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, the new people, have close relationships to China.

The West has long been afraid of China’s growing influence, especially in the developing world, even though the development may not have directly contributed to the result of the G20 summit.

According to Pramit Pal Chaudhuri, South Asia training head of the Eurasia Group,” It wasn’t a primary issue, but the West, particularly the US, is aware that China is actively attempting to establish an anti-Western global order.”

It is also well known that the West views India as China’s counterbalance and would not have preferred for Delhi to close its administration without making a statement.

Therefore, there were numerous reasons why the West supported India in reaching a discussion.

The conflict in Ukraine was the principal sticking point. The G20’s Bali announcement from the previous year had criticized” brutality by the Russian Federation against Ukraine” and noted some members’ objections to this assessment.

It seemed improbable that the West would accept vocabulary that was less powerful than the one used in Bali, and Russia even made it clear that it would not accept a claim that Russia was to blame for the conflict.

India was in a great position to mediate the necessary find because it has cordial relations with both Moscow and the West.

The declaration ultimately used vocabulary that satisfied both Russia and Eastern nations.

It was evident that the West wanted India to succeed diplomatically. A settlement was always required. However, if there were issues in the language on which they could never reach an agreement, the US and the West would not have agreed to a mutual resolve, according to Angela Mancini, partner and head of Asia-Pacific markets at firm company Control Risks.

Analysts believe that the Delhi announcement was more forgiving than the Bali declaration in not blaming Russia for the battle. The” individual suffering and negative ramifications of the fight in Ukraine on world food and energy safety” was, however, addressed.

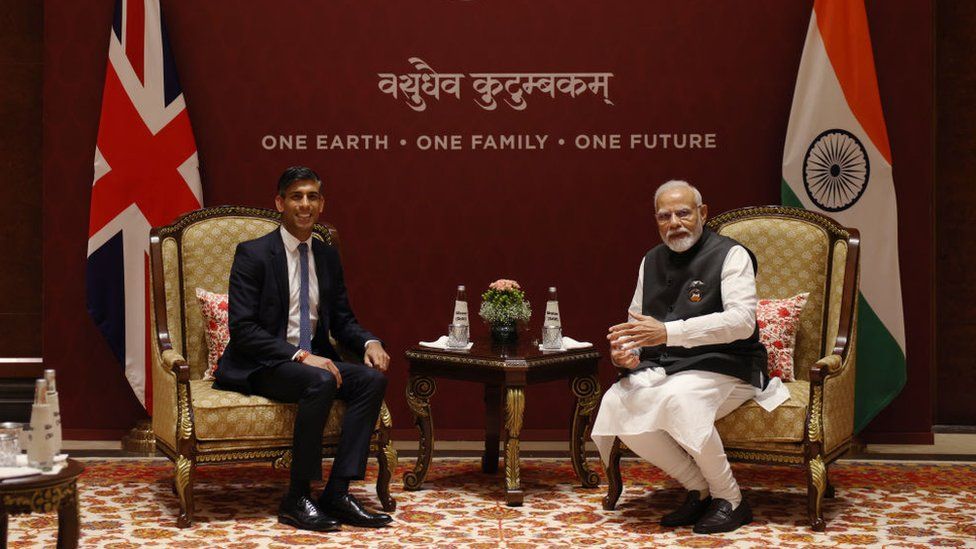

Officials from the UK, the US, and France ultimately seemed to concur with Russia that the summit’s announcement was a positive outcome. But, the wordings were interpreted differently by the two sides.

The declaration, according to UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak,” had strong language, highlighting the impact of the war on food prices and food protection.” Sergei Lavrov, the foreign secretary of Russia, referred to the Delhi tip as a milestone.

Ukraine, however, has been upset by the sudden deal because it claimed the G20 had nothing to be happy of.

Prior to the summit, one of the main worries was the debt problems that many developing nations were experiencing.

Developing countries have long argued that wealthy countries need to boost their support in order to support their markets. The epidemic battered these, and the conflict has made their difficulties worse. The world’s poorest nations owed$ 62 billion in annual loan services to creditors, with China owing two-thirds of this, according to a World Bank report from December.

European officials have frequently accused China’s lending practices of being aggressive, but Beijing disputes this claim.

The charter could have been vetoed by China, which is closely allied with Russia, but it was not. China is not explicitly or indirectly mentioned in the article about the debt problems.

” In terms of debt reduction, we did not observe any advancement.” Any criticism of banking procedures, according to Mr. Pal Chaudhari, would have been seen in many ways as an anti-China walk.

The declaration acknowledged the crisis and urged the G20 countries to accelerate the common framework’s( CF ) implementation, which was agreed upon in 2020 to aid vulnerable countries.

Despite the fact that the G20 countries account for nearly 80 % of greenhouse gases, the team agreed to tripling renewable energy capacity by 2030 but did not set any significant emission reduction goals.

Importantly, the announcement focused on phasing out the use of fuel rather than mentioning any targets for lowering the consumption of crude oil. Saudi Arabia and Russia’s simplistic producers would have been content with this. The West’s emission cut targets, which they consider to be” implausible ,” have even caused discomfort in China and India.

Delhi undoubtedly put a lot of effort into gaining discussion, even if it meant making significant concessions.

It’s not surprising that some of the vocabulary was a little muffled in some places to reach that compromise, says Ms. Mancini, given that the document had to be one.

The addition of the African Union in the G20 was one issue that brought the class together even before the mountain.

It strengthened Delhi’s efforts to give developing countries from the Global South more influence on international forums.

This was” one of the most difficult G20 delegations” in the forum’s nearly 25-year history, according to a Russian government communicator. According to Svetlana Lukash of the Russian news agency Interfax, it took nearly 20 days to reach an agreement on the charter prior to the conference and five days in person.

Whether the G20 unites the wealthy and developing countries or splits the earth into two tents remains to be seen.

More information about this tale

-

-

two days ago

-

-

-

two days ago

-

Russia hails unexpected G20 ‘milestone’ as Ukraine fumes

EPA

EPASergei Lavrov, the foreign secretary of Russia, has praised a joint statement made in Delhi by the G20 leaders that refrains from denouncing Moscow for its war against Ukraine.

According to Mr. Lavrov, Russia had not anticipated a compromise and that deal on the language was” a step in the right direction.”

The African Union was even admitted as a permanent part during the two-day height.

The 55-member union joins at the offer of hosts India, whose president has made it a priority to increase the inclusion of so-called Global South nations in the G20.

Although there was censure of the tournament’s failure to send to phase-outing fossil fuels, the largest economies in the world reached another significant agreements in Delhi, including one on weather and biofuels.

There was no established G20″ family picture” for the second time in a column. There was no explanation given, but according to reports, many officials declined to be photographed, indicating that Russia was present at the conference.

Some people, not least on the summit’s opening moment, had anticipated a joint announcement at the G20 this year. Regarding Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last year, the group is bitterly fragmented. Neither Xi Jinping of China nor Vladimir Putin of Russia showed up in Delhi, sending lower-level ambassadors in their place.

Therefore, it came as a shock when Indian Prime Minister Mr. Narendra Modi announced that the Ukraine part of the statement, which had last month’s direct criticism of Russia watered down, had reached consensus just hours after the summit began.

On Sunday, Mr. Lavrov declared that a” step” had been accomplished.

Sincerely, we didn’t anticipate that. We were prepared to defend the text’s language. In response to a query from the BBC’s Yogita Limaye, he stated that” the Global South is no longer willing to be lectured.”

The joint statement was promoted by the UK and the US as well, but Ukraine, which attended the Bali summit last year but was not invited this year, claimed it was” nothing to be happy of.”

The majority of users expressed” in the strongest terms” their regret for the Russian Federation’s aggression against Ukraine in Bali next year. The Delhi announcement, in contrast, discusses” the people suffering and additional negative effects of the war in Ukraine with regard to international food and energy security.”

In addition to urging state to” abstain from the threat or use of force to get regional skill ,” which could be interpreted as being directed at Russia, it also mentions” different views and analyses of the condition.”

According to analysts, the G20’s financial balance and power dynamics are shifting apart from Western developed market economies and toward emerging giants, especially in Asia.

There were other significant events at the tip as well, such as significant agreements aimed at combating climate change.

A complete agreement has been reached among the G20 members to” do and stimulate efforts to triple global renewable energy capacity through existing targets and policies.” More than 75 % of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions come from the union.

In order to encourage the use of cleaner fuels, India also established a global biodiesel alliance with the US and Brazil. By facilitating industry in renewables made from plant and animal waste, the clustering aims to hasten international efforts to achieve net zero emissions targets.

On the outside of the conference, there was also a global road and port agreement connecting the Middle East and South Asia. The agreement is seen as a response to China’s Belt and Road initiative to improve world equipment.

Mr. Modi concluded months of hype and excitement by closing the summit early on Sunday evening. President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva of Brazil, who is assuming the presidency, received a royal hand from him.

President Lula’s talk was largely focused on issues facing developing nations.

He claimed that” we are living in a world where money is more concentrated, where millions of people continue to go hungry, in which sustainable development is perpetually threatened, and where global government institutions still reflect the reality of the 20th century.”

Leaders walked in the rain to honor Mahatma Gandhi, India’s independence warrior, at the location of his death because the rain downpours had derailed some earlier-in-the-day plans. A meeting to plant trees was downgraded to a symbolical swap of trees between G20 presidents in the past, present, and potential.

Delegates were treated to social shows, a gala dinner party, and the best of American hospitality as part of Mr. Modi’s luxurious show, which was put on from beginning to end.

However, it also sparked some debates, particularly after Mr. Modi’s sign, which introduced India as” Bharat”( which means India in Hindi ) as he opened the summit, suggested that the nation might change its name.

But, Mr. Modi and his officials hailed the occasion as a huge success and claimed that India’s G20 administration had demonstrated its leadership skills on the international stage.

Foreign Minister S Jaishankar stated,” We have sought to make this G20 as inclusive as possible.”

According to Nirmala Sitharaman, the finance minister, India has succeeded in preventing issues from obscuring the fundamental development issues facing the world.

She stated that” India’s G20 Presidency has walked the discuss safely.”

The case for Bilawal Bhutto as Pakistanâs next prime minister

Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, a 34-year-old politician from Pakistan with an Oxford education and the head of the Pakistan People’s Party ( PPP ), is the grandson of late Zulfiqar Ali and son of former prime minister Benazir Bhatto. Bilawal, who comes from a political community and possesses strong statesmanship skills, has quickly shown that he is capable of serving as prime minister of Pakistan.

Bilawal serving as a foreign secretary

His position was significantly strengthened by his tenure as Pakistan’s foreign minister( April 2022 – August 2023 ). The ability of Bilawal Bhutto to efficiently represent Pakistan on the international stage, navigate complicated international relations, and advance Pakistan’s interests was highlighted by his leadership qualities and performance.

Bilawal Bhutto worked to strengthen relationships with local nations and emphasized the value of regional cooperation during his brief career. Local stability and economic integration, which are essential for Pakistan’s growth and security, were generally given top priority by Bilawal.

His efforts to interact with local powers like Iran, Afghanistan, and India showed his dedication to resolving disputes and fostering peace in the area. His vision for local assistance promotes a more stable and prosperous South Asia by serving the interests of Pakistan and its neighbors.

The efforts of Bilawal to strengthen Pakistan’s financial ties with China, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and other nations have been successful, attracting foreign direct investment and opening doors for financial expansion.

His emphasis on financial diplomacy showed that he recognized the significance of a strong market for the total development of the nation.

defending animal rights

In Pakistan, the PPP has a history of standing up for immigrants and human rights. In this regard, Bilawal Bhutto’s dedication to individual freedom, advocacy for Baloch and Pashtuns, and calls for social justice are clear. He has consistently fought against human rights violations around the world, highlighting Pakistan’s position on these problems, especially in Kashmir and Palestine.

Bilawal’s fervent support for justice and equality resonates with people around the world and demonstrates how dedicated Pakistan is to upholding basic right. His initiatives to encourage Pakistan’s position on individual rights and work with international organizations, particularly the UN and Amnesty International, show his ability to take the lead on international issues.

securing relations

In terms of Pakistan’s ties with international forces and balancing relationships, the stints of former prime minister Imran Khan and foreign secretary Shah Mahmood Qureshi were utterly insufficient and unsettling.

Bilawal made sure that Pakistan’s independence and national interests were protected by skillfully navigating the challenges of its relations with the United States, the European Union, China, and other big power. His capacity to effectively manage Pakistan’s foreign alliances and his ability to maintain a healthy approach in international relations were both demonstrated by his diplomatic prowess.

Moreover, he has actively worked to resolve regional conflicts, such as reestablishing cordial ties with Afghanistan, Iran, the Arab world, and India.

Prime Minister, why?

As prime minister, Bilawal has been positioned as a worthy leader to direct Pakistan’s foreign policy due to his thorough understanding of the challenges and opportunities facing Pakistan around the world and his proper vision.

His social savvy, which portrays him as the leader of the country’s new creation, demonstrates his ability to lead Pakistan. His command qualities were evident in his political abilities, emphasis on local assistance, promotion of financial diplomacy, advocacy for individual rights and social justice, capacity to mediate international alliances, crisis-management skills, and vision for Pakistan’s foreign policy.

Bilawal’s personality was accentuated by his ability to effectively represent Pakistan on the global stage and navigate convoluted foreign relations. Bilawal Bhutto has the possibility to become prime minister of Pakistan thanks to his corporate vision and dedication to the country’s stability and development.

Bilawal Bhutto Challenges

The long-running Kashmir debate with India is one of the most important regional issues for Pakistan. It is crucial to handle the Kashmir matter for peace and stability in the North Eastern area. Trade and business alliances between the local claims have been severely impacted by the problem.

To find a peaceful solution to the problem, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari would need to work with India and the global community for regional communication and economic participation. & nbsp,

For Pakistan’s personal safety, maintaining balance in Afghanistan is also essential. Particularly Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan Islamic State of Khorasan Province militants have been greatly encouraged by the Afghan Taliban’s rise. The peace and stability of Afghanistan and Pakistan are seriously threatened by their appearance there.

Bilawal Bhutto had face significant obstacles in his efforts to forge a secure and peaceful relationship with Afghanistan through political efforts and assistance, including reestablishing normal relations with the Afghan state and combating the threat of militancy.

Pakistan hasn’t had good ties with Iran since the US imposed sanctions on it to end its nuclear programme. Pakistan’s economy would not be able to stabilize without cordial and firm ties with Iran.

It is essential to improve relations with Iran, particularly in the areas of business and power cooperation. Iran is a state with abundant fuel. Iran offers affordable diesel, gas, and non-oil products to Pakistan. It would be a significant problem for Bilawal to find ways to improve diplomatic ties if he ignored US force and grew closer with Iran. & nbsp,

The economy of Pakistan needs steady progress and balance. The main obstacle for Bilawal as prime minister would be integrating with international financial institutions, luring foreign investment, and putting good economic policies in place to revive Pakistan’s faltering business. & nbsp,

In other words, the Pakistan People’s Party, under the leadership of Bilawal Bhutto, stands a good chance of establishing the second federal government. The party’s possible success is influenced by its historical importance, Bilawal ‘ leadership qualities, appeal to the children, commitment to democracy and cultural justice, strong party architecture, regional and majority support, and the anti-incumbency issue.

However, it’s crucial to remember that social scenery can change and that the results of elections depend on a variety of factors. However, the PPP makes a strong case for Pakistani government while being led by Bilawal Bhutto.

G20 laments war in Ukraine but avoids blaming Russia

shabby graphics

shabby graphicsA joint resolution, which includes a statement on the conflict in Ukraine, has been agreed upon at the G20 summit in India.

The G20 leaders condemned the use of force for regional gain on the first day of their two-day meeting, but they refrained from criticizing Russia instantly.

The statement, according to the Polish government, is” nothing to be happy of.”

A number of international issues, such as climate change and the debt burden on developing nations, were also covered at the elevation in Delhi.

But at the G20 summit, it was a time of unexpectedly significant articles.

Given the strong divisions within the team over the conflict in Ukraine, some anticipated a joint resolution, not least on the first day of the mountain.

However, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared that the resolution had received widespread support.

An earlier review of the charter that was accessed by the BBC on Friday contained a clear indication that last-minute negotiations were ongoing: it stated the paragraph on Ukraine was left vacant.

The Ukraine conflict was the sticking point, as it was at the Bali summit the previous year.

The Delhi Declaration seems to be intended to make it possible for both Russia and the West to get advantages. However, in the process, it has used terminology that is less forceful in its criticism of Moscow than it was in Bali the previous year.

Although it noted that” there were other landscapes and different analyses of the condition and sanctions ,” the people in Bali condemned” in the strongest term” the brutality by the Russian Federation against Ukraine.

Russia is not immediately criticized for the war in the Delhi resolution.

However, it does mention” the human suffering and additional negative effects of the Ukrainian war on the world’s food and energy security.” Additionally, it reiterated the acknowledgment of” different perspectives and evaluations.”

Importantly, rather than” the war against Ukraine ,” the declaration refers to the” war in Ukraine.” The probability that Russia would support the resolution may have increased as a result of this word choice.

Ukraine, which participated in the Bali conference, was never invited this time, and its reaction to the resolution has been negative.

The Russian foreign ministry tweeted,” G20 has nothing to be glad of in terms of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.”

The African Union( AU) was formally invited to join the G20 as a permanent member by Mr. Modi, which was the other major development.

As the cornerstone of its president, Delhi prioritized elevating the tones of these countries. In the near future, it is prepared to benefit from this strategic decision as it competes with China for influence in Asia and Africa.

The choice is also great news for Africa, which has 1.4 billion inhabitants and will now have a larger voice at international events like the G20.

Another fiercely debated subject was climate change.

There had been no consensus on the matter at the governmental level meetings in the weeks leading up to the mountain. However, officials now claim to have reached” 100 % consensus.”

There has been a clear give-and-take on the environment in the resolution.

The G20 nations will” pursue and encourage efforts to triple renewable energy capacity globally through existing targets and plans ,” according to the statement. More than 75 % of greenhouse gas emissions come from G20.

In the past, developing countries had resisted raising their goals for renewable energy, cutting back on fossil fuel use, and lowering their emissions of greenhouse gases.

Developing countries have been able to buy day for greenhouse pollution to peak, at which point they will need to decrease.

According to the declaration,” timeframes for rising may be shaped by sustainable development, needs for poverty eradication, equity, and in accordance with various federal circumstances.”

The Green Development Pact, a plan to address the climate crisis through international cooperation over the next ten years, has also been emphasized by specialists.

In order to assist developing nations’ transitions to lower emissions, the G20 nations have also committed to working together to provide low-cost financing.

India had performed” fairly well” on natural finance, according to Pramit Pal Chaudhuri, head of the Eurasia Group’s South Asia practice.

” Green finance presently primarily originates in wealthy nations and travels between rich nations.” Private funding is essential to this funding. Yet emerging markets don’t grasp it. India has made efforts to alter that. Getting multilateral development banks to start de-risking private capital moves in the clean space is at the heart of it, he said.

Then there is the rising worry about debts. According to the World Bank, the world’s poorest countries have to pay bilateral creditors an annual debt service of more than$ 60 billion, which increases the likelihood of defaults. China is owed two-thirds of this bill.

The organization has stated that it wants to aid in the loan management of these nations. The Delhi Declaration has pledged to handle the country’s loan risks.

Navin Singh Khadka provided extra coverage.

On this account, more

-

-

a day before

-

-

-

a day before

-

How countries prepare for population growth and decline

India overtook China as the most populous nation in the world at the beginning of this year, with China having 850, 000 fewer individuals by the end of 2022, marking the nation’s earliest population decline since the famine that struck from 1959 to 1961.

Given China’s current population of 1.4 billion, this reduction may seem respectable, but it is expected to continue. According to UN projections, China may have fewer than 800 million people living there by the year 2100.

Communities change as a result of emigration, immigration, deaths, and birth. China’s past one-child plan, which was in effect from 1980 to 2015, slowed its birth rate as a result of gender inequality. The Chinese authorities is currently working to increase delivery charges, including by outlawing pregnancy.

According to the 18th-century The & nbsp Malthusian population growth model, populations grow exponentially and outpace resource availability until unavoidable obstacles like famine, disease, conflict, or other problems cause it to decline.

These worries were prevalent in the early 1960s, during the high global population growth rates of & nbsp. However, population growth has drastically slowed globally, and healthy decline is currently underway in China and many other nations.

According to current population trends, a 2020 study published in the Lancet medical journal & nbsp found that more than 20 nations are on track to halve their populations by 2100. While the Center of Expertise on Population and Migration( CEPAM ) predicts the global population will peak at 9.8 billion around & nbsp, 2070 to 2080, the Pew Research think-tank predicted that 90 countries‘ populations would decline by 2100.

Governments and economics everywhere are plagued by the worry of an aging and shrinking population. A reduced labor force will be put under strain by increased payment to the pension and social security systems, while younger communities may also add more to financial growth and innovation. Countries may also see a decline in their influence on the world, no the least of which is the smaller community that is available for military service.

The total fertility rate ( TFR ), which measures the number of children a woman will have in her lifetime, is the most prevalent of the metrics that measure fertility and birth rates. However, it has proven difficult to achieve replacement-level fertility rates, which are usually 2.1 children and nbsp per female.

The decline in global fertility rates may be attributed to societal and cultural changes, family planning initiatives, expanded access to contraceptives, improved child mortality rates, increased cost of child rearing, urbanization, postponed marriages and pregnancy due to educational and career pursuits, and social welfare systems that lessen reliance on parental support.

Asia’s north

A prime example is Japan, whose inhabitants peaked in 2008 at 128 million and has since decreased to less than 123 million. By the end of the century, it is expected to have a population of 72 million, with its decline being supported by low fertility rates, an aging population( almost andnbsp, 30 % of people are 65 or older ), and limited immigration. Changes to immigration laws, government-sponsored speed dating, and other measures are being taken to decrease this decline.

Surprisingly, despite reaching a record low & nbsp in 2022, Japan’s TFR is now higher than those of China and South Korea. More than US$ 200 billion has been invested by South Korea since 2006 in the creation of common nursery facilities, free gardens, discounted care, and other programs to increase its TFR. & nbsp, However, South Korea’s TFR continues to be the lowest in the world at 0.78.

Earlier in the 21st century, South Korea’s state also implemented immigration reforms, all the while leading the world in technology with 1, 000 robots per 10,000 employees, more than twice the price of second-ranked Japan.

Europe

In Europe, efforts to increase population have been ongoing for a long time. For instance, in 1966, Romania & nbsp made abortion illegal and outlawed contraception, with the exception of certain medical conditions. As a result, there were more improper abortions, and in the 1980s Romania had the highest level of maternal mortality in all of Europe.

Romania’s TFR stabilized at 2.3 % by the late 1980s, but it collapsed in the 1990s along with immigration and nbsp, a community migration that has been ongoing since Romania joined the European Union in 2007.

Similar Birthrate declines and emigration have occurred in different Eastern European countries andnbsp. Western European nations, on the other hand, have only been able to grow marginally since 2000, primarily as a result of emigration. However, populations have been declining in nations like Italy, which has prompted government efforts to sell homes to immigrants for as little as€ 1 in an effort to repopulate small towns.

a country in the U.S.

In comparison to the majority of European nations, the US has a lower average age and nbsp. In the 2000s, TFR prices also increased. However, this decreased after the 2008 crisis and has never fully recovered.

And in contrast to Western nations, living expectancy continued to decline following the Covid-19 pandemic. These problems have been alleviated by Immigration & nbsp, but the US population growth rate has significantly slowed as a result of political unrest in Europe.

The US and nbsp promote family-planning initiatives internationally even though there is no official plan to increase birth rates.

Since 1984, the Mexico City Policy, which mandated that foreign non-governmental organizations ( NGOs ) not” perform or actively promote abortion as a method of family planning” in order to receive US government funding for family-planning initiatives, has oscillated between the Republican and Democratic administrations.

Russia

Following the fall of the Soviet Union, Russia’s TFR experienced a sharp drop that peaked at 1.16 in 1999 and led to people decline. Authorities efforts, however, saw it rise to 1.8 in 2014 before falling once more.

The Kremlin announced increased bills for kids of at least two youngsters as well as the desired TFR of 1.7 in 2020. Russia has even relied on immigration to further stabilize its people.

Iran

Iran’s policies regarding birth rates have changed over the past several years. Iran & nbsp implemented fertility controls in the 1950s, but they were eliminated following the 1979 Islamic Revolution. But, they were reintroduced in the late 1980s to ease economic force.

Iran’s TFR, once regarded as a” success story,” decreased more quickly than expected to 1.6 in 2012. The government started limiting exposure to birth control, abortion, and vasectomies in an effort to increase the delivery rate that time.

Asia South

India currently holds the title of most popular nation in the world, but its TFR is currently below replacement levels. Despite this, its people will keep expanding thanks to a sizable, young population— a demographic trait that is becoming more prevalent throughout the Global South.

While it is ultimately anticipated that India’s population will start to decline by the 2060s, the country is currently managing its young population through initiatives andnbsp, such as fostering employment opportunities abroad.

Beyond untapped financial possible, there are risks associated with not using a sizable working population and nbsp. Big young populations can cause major social and political upheaval in the absence of financial prospects. Pakistan is attempting to slow down its population growth in order to prevent aggravating pressures on its resources, system, educational system, and healthcare systems.

home organizing

Pakistan’s worries resemble those of a large portion of Africa. The top 20 nations with the highest TFR & nbsp, excluding Afghanistan, are all located in Africa. Nigeria’s population is expected to increase from 213 million to 550 million & nbsp by the year 2100, and some projections show that between 2020 and 2050, half of all births will occur in Africa. However, family planning programs have aided slower progress across the globe in recent years.

In contrast, the experience of nations where fertility-supporting campaigns have had some success( such as & nbsp, Germany, and ThenBsP, Czech Republic and Hungary ) suggests that direct financial incentives, tax breaks, affordable / free childcare facilities, generous maternity / paternity leave, housing assistance, as well as more adaptable approaches to work-life balance, are effective at halting decline.

In the past, gender equality has frequently been cited as a challenge to higher delivery costs, but this doesn’t seem to be the case anymore. For instance, in 1980, highly educated women in the US and nbsp had the lowest fertility level; however, this was untrue in 2019.

Also, by 2005, Mongolia’s TFR had decreased from 7.3 children per woman in 1974 to under two. & nbsp, But by 2019, Mongolian birth rates had risen to about three children per woman, despite the fact that women in Mongolia were becoming more educated, more represented in the population, in traditionally male-dominated fields, and had better access to rural maternal health services.

However, the recent population boom & nbsp in Mongolia has led to problems like housing shortages, pollution, school crowding, and other problems, necessitating the development of flexible strategies for population stabilization and growth.

Different parts of the world will need different measures to deal with fluctuating population numbers this century, with a median age of 44.4 years & nbsp in Europe and one of about 19 in Africa.

China is not the only nation that believes that it will age before becoming wealthy, and that such nations will create their own strategies to deal with aging cultures. Priority should be given to developing long-term green approaches to people management that avoid force but also offer assistance for those raising children.

Asia Times received this article from & nbsp, Globetrotter, who also produced it.

Slums hidden as India puts on its best face for G20

shabby pictures

shabby picturesYou will come across billboards with Bollywood stars endorsing several products on any given time as you stroll down an American road.

However, over the past year, G20 summit banners have appeared everywhere in the nation. They have been displayed on sizable LED displays and are taped to power poles and tucked behind uk-tuks.

The posters prominently feature India’s official G20 logo, which is compared to the Bharatiya Janata Party( BJP ) symbol and features a globe encircled by blooming lotuses. They are accompanied by images of Prime Minister Modi, Narendra.

The government wants to convey that India has entered the global level.

The nation has hosted 200 pre-summit meetings with yoga, cultural performances, and specially curated menus in more than 50 cities, with a reported budget for hosting the G20 exceeding$ 100 million(£ 78 million ).

On American news channels, there has been perplexing policy of events for months in an effort to entice even those who are typically blind to the subtleties of foreign policy.

Now that the principal summit is only two days away, Delhi has been prepared for what is regarded as the most high-profile occasion to be held in India in recent memory.

The American flag, rose pots, and sculptured fountains have all been erected throughout the city. The mountain logo has been placed on dozens of historic sites, and people are swarming to take selfies. Famous flowers in the city have undergone a makeover, their leaf has been freshly pruned, and flags of participating countries have been flown.

However, there is another aspect to the decoration campaign. Some neighborhoods have temporary fabric walls built in front of them to block their view, and in some cases, occupants have been moved. It’s unclear where the gypsies have been relocated after being evicted from the center of the city.

In advance of the event, the state has declared three days of vacation for the majority of schools and offices, closed important bridges, and deployed thousands of security personnel. Numerous railways and flights have been canceled.

Never before has India hosted so some world leaders simultaneously.

The G20 is the most crucial platform to reach India’s goal of bridging the gap between international policy and local government. Former American ambassador Jitendra Nath Misra claims that the government is aware of this.

However, despite the carnival-like atmosphere, Delhi will still face the difficult task of preventing problems from derailing its goals, such as the Ukraine war, which tore the group apart at the G20 summit in Bali next year.

” India did hope that agreeable issues rather than controversial people like Ukraine will be the focus.” Although it hasn’t been able to do that thus much, Mr. Misra predicts that it will do so in the future.

India has stated that since taking office as president of the G20, it wants to prioritize issues that have a overwhelmingly negative impact on developing countries, such as climate change, rising debt, digital transformation, inflation, and food and energy security.

According to Happymon Jacob, a professor of foreign policy at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, the conference will take place as the” Global South” has managed to establish itself as an important player in the international order and Western nations have realized that” their exclusive venues may alone solve the problems of the world.”

Many nations then question the value of a website dominated by the West like the G20, which they assert is focused on an outmoded international distribution of power, in light of rising inequality, great food and fuel prices, and climate change.

This, according to Mr. Jacob, was most obvious during the crisis, when India assisted nations in Africa, South Asia, and also China,” while the European countries were just looking after themselves.”

In the future, there must be” a converging point” between the two sides of the globe, and India hopes to provide that at the summit.

” We are with you and we are willing to result from the front,” the communication was sent to the local populace and the Global South. You never afford to ignore the worries coming from this region of the world under India’s command, Mr. Jacob continues, adding to the global community.

For example, Mr. Misra claims that India’s willingness to support developing nations is reflected by the plan to include the African Union in the G20.

India believes it has the power and resources to accomplish this because it is one of the world’s most prosperous financial regions.

The Delhi state, however, will find it difficult to try to bridge the gap between developed and developing nations because of its precarious geopolitical location.

Given how much money it has spent promoting a G20 summit under Mr. Modi’s authority, it will also be under pressure to produce results internally. He will want to demonstrate his ability to strengthen India’s position in the global community, particularly during the months leading up to the general vote the following year.

Usually, international policy hasn’t had much of an impact on Indian democratic elections unless it’s about the immediate region, like Pakistan or China, or the US in recent years.

But under Mr. Modi, that is changing because both he and Indians are idealistic and concerned with their standing in the world.

” He has established himself as a leading international diplomat. That image would be enhanced by a significant and effective performance at the G20, according to Mr. Jacob.

Even if Ukraine disrupts the mountain, according to Mr. Misra, people will” look at the carnival, the great show” and believe it has improved the nation’s standing on the international stage.

However, Mr. Modi has a lot of job to do at home, including creating employment for millions of people, for instance.

Then there are issues with individual rights. Since Mr. Modi took office in 2014, according to opposition events and protesters, there has been an increase in hate crimes against Muslims and other people. However, his government refutes these claims, claiming that all Indians have been covered by its guidelines.

And during the conference, Mr. Modi wants to convey that message to both domestic and international audiences.

Learn more BBC reports about India here: