The ‘flying rivers’ causing devastating floods in India

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHeavy rains and floods have affected several parts of India in recent weeks, killing scores of people and displacing thousands of others.

Floods are not uncommon in the country – or South Asia – at this time of the year, when the region receives most of its rainfall.

But climate change has made monsoon rains more erratic, with massive rainfall in a short span of time followed by prolonged periods of dryness.

Now scientists say that a type of storm, known as an atmospheric river, is making things worse with a significant increase in moisture because of global warming.

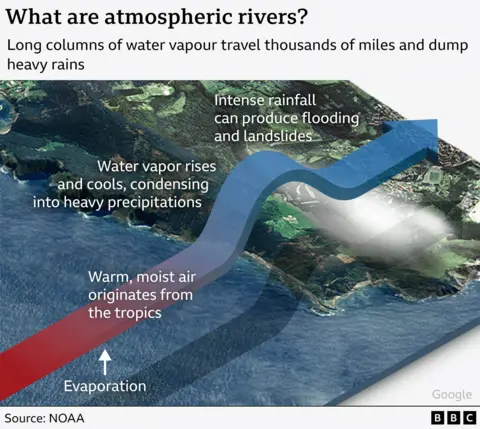

Also known as “flying rivers”, these storms are huge, invisible ribbons of water vapour that are born in warm oceans as seawater evaporates.

The water vapour forms a band or a column in the lower part of the atmosphere which moves from the tropics to the cooler latitudes and comes down as rain or snow, devastating enough to cause floods or deadly avalanches.

These “rivers in the sky” carry some 90% of the total water vapour that moves across the Earth’s mid-latitudes and, on an average, have about twice the regular flow of the Amazon, the world’s largest river by the discharge volume of water.

As the earth warms up faster, scientists say these atmospheric rivers have become longer, wider and more intense, putting hundreds of millions of people worldwide at risk from flooding.

In India, meteorologists say the warming of the Indian Ocean has created “flying rivers” that are influencing monsoon rains between June and September.

A study published in the scientific journal Nature in 2023 showed a total of 574 atmospheric rivers occurred in the monsoon season in India between 1951 and 2020, with the frequency of such extreme weather events increasing over time.

“In the last two decades, nearly 80% of the most severe atmospheric rivers caused floods in India,” it said.

A team of scientists from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) and the University of California, who were involved in the study, also found that seven of India’s 10 most severe floods in the monsoon seasons between 1985 and 2020 were associated with atmospheric rivers.

The study said evaporation from the Indian Ocean had significantly increased in recent decades and the frequency of atmospheric rivers and floods caused by them has increased recently as the climate has warmed.

“There is an increase in the variability [more fluctuations] in the moisture transported towards the Indian subcontinent during the monsoon season,” Dr Roxy Matthew Koll, an atmospheric scientist with the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, told the BBC.

“As a result, there are short spells when all that moisture from the warm seas is dumped by the atmospheric rivers in a few hours to a few days. This has led to increased landslides and flash floods across the country.”

An average atmospheric river is about 2,000km (1,242 miles) long, 500km wide and nearly 3km deep – although they are now getting wider and longer, with some more than 5,000km long.

And yet, they are invisible to the human eye.

“They can be seen with infrared and microwave frequencies,” says Brian Kahn, an atmospheric researcher with Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“That is why satellite observations can be so useful for observing water vapour and atmospheric rivers around the world,” Mr Kahn added.

There are other weather systems like westerly disturbances, monsoon and cyclones that can cause floods as well.

But global studies have shown that atmospheric water vapour has increased by up to 20% since the 1960s.

Scientists have associated atmospheric rivers with up to 56% of extreme precipitation (rainfall and snowfall) in South Asia, although there are limited studies on the region.

In neighbouring Southeast Asia, there have been more detailed studies on the links between atmospheric rivers and monsoon-related heavy rains.

A 2021 study, published by the American Geophysical Union, found that up to 80% of heavy rainfall events in eastern China, Korea and western Japan during early monsoon season (March and April) are associated with atmospheric rivers.

“In East Asia there has been a significant increase in frequency of atmospheric rivers since 1940,” says Sara M Vallejo-Bernal, a researcher with the University of Potsdam in Germany, who led a separate study.

“We found that they have become more intense over Madagascar, Australia and Japan ever since.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMeteorologists in other regions have been able to link a few recent major floods to atmospheric rivers.

In April 2023, Iraq, Iran, Kuwait and Jordan were all hit by catastrophic flooding after intense thunder, hailstorms and exceptional rainfall. Meteorologists later found that the skies across the region were carrying a record amount of moisture, surpassing a similar event in 2005.

Two months later, Chile was hit by 500mm of rain in just three days – the sky dumped so much water that it also melted snow on some parts of the Andes mountain, unleashing massive floods that destroyed roads, bridges, and water supplies.

A year earlier parts of Australia had been hit by what politicians called a “rain-bomb”, with more than 20 people killed and thousands evacuated.

Given the risks of catastrophic floods and landslides they can trigger, atmospheric rivers have been categorised into five types based on their size and strength – just like hurricanes.

Not all of them are damaging though, especially if they are of low intensity.

Some can be beneficial if they land in places that have suffered from prolonged droughts.

But the phenomenon is an important reminder of a rapidly warming atmosphere that holds much more moisture than in the past.

At the moment, the storm is relatively under-studied in South Asia, compared to other weather events like western disturbances or Indian cyclones that are the other major causes of floods and landslides.

“Effective collaborative efforts among meteorologists, hydrologists and climate scientists is currently challenging as the concept is new in this region and difficult to introduce,” said Rosa V Lyngwa, a research scholar at IIT Indore.

But as heavy rains continue to pummel parts of India, it’s become more important to study this storm and its potential devastating impact, she adds.

Additionally, he highlighted the emergence of a circular economy to facilitate long-term sustainability, as being a growing trend: “Look at the battery ecosystem for example, a huge industry is developing around the recycling of batteries – additionally the recycling of solar panels, turbines and so forth is being considered. The recycling industry is becoming larger as ultimately, unless there is a circular economy around it, resources will be wasted. New action is being taken to develop a fully circular product lifecycle.”

Additionally, he highlighted the emergence of a circular economy to facilitate long-term sustainability, as being a growing trend: “Look at the battery ecosystem for example, a huge industry is developing around the recycling of batteries – additionally the recycling of solar panels, turbines and so forth is being considered. The recycling industry is becoming larger as ultimately, unless there is a circular economy around it, resources will be wasted. New action is being taken to develop a fully circular product lifecycle.”