Quad to survive and thrive after Biden, Kishida – Asia Times

The third in-person Triple officials ‘ summit was held in Wilmington, Delaware, the town of US President Joe Biden, on September 21, 2024 amid confusion about the grouping’s potential.

The conference marked the end of a certain time because it was the next meeting to feature retiring US President Biden and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida.

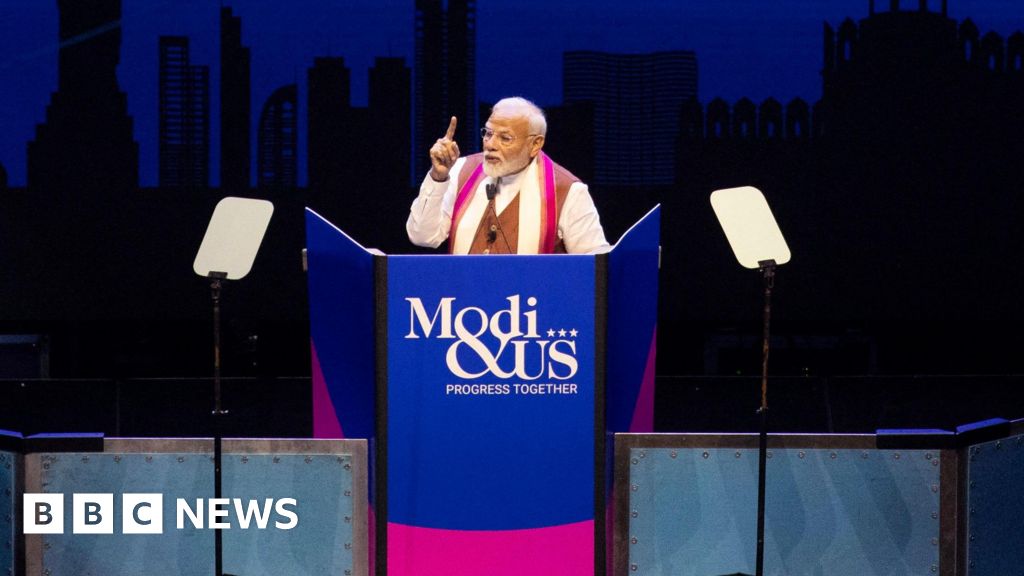

In order to host the summit in his last year as president, Biden and India agreed that the US and India had exchange host years, giving Prime Minister Narendra Modi the opportunity to do so.

Another real reason for holding the Quad in the US was that it gave Kishida one more chance to participate before the governing Liberal Democratic Party’s ( LDP ) presidential election on September 27, 2013.

Kishida, who is not running for re-election, is attending his past political function as prime minister, along with Modi and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, at the United Nations General Assembly.

Functional outcomes

The Indo-Pacific Quad’s incarceration efforts and reputation as a service of public goods are further strengthened by the Wilmington Declaration. The charter introduced six new activities:

- The Indo-Pacific country’s cancer death rate is being reduced by the Quad Cancer Moonshot Initiative. The Quad states will expand treatment options and care, improve access to tests, and encourage more HPV vaccines to combat cervical cancer, possibly saving the lives of millions of women. They will do this thanks to innovations developed in Queensland, Australia.

- Increasing training and enhancing existing capacities to ensure that regional partners can continue to strengthen their ability to thwart illegal marine operations through the expansion of the Quad Indo-Pacific Partnership for Marine Domain Awareness ( IPMDA ).

- By bringing together Triple partners to create a joint Triple aircraft power, the Indo-Pacific Logistics Network Pilot aims to increase the performance, performance, and timeliness of humanitarian aid and the response to natural disasters in the Indo-Pacific region.

- In order to improve maritime security and interoperability among Quad coast guard units, the second Quad-at-Sea send spectator goal will be launched in 2025 as part of the Quad Coast Guard Cooperation.

- However, in collaboration with governments in Southeast and South Asia as well as Pacific area states, the Quad will create an Indo-Pacific sea training program – MAITRI, which means “friendship” in Sanskrit. Now, Quad member states provide individual instruction for these nations, including exercises in sea rescue and improper fishing monitoring. The planned initiative aims to increase their performance by synchronizing the exercises to minimize clash. The first MAITRI workshop may be held in India in 2025.

- A quadratic coastal legal dialogue will help to advance the Indo-Pacific’s rules-based sea order.

The Delaware Summit commemorated the Quad’s 20th celebration. The Quad was established in 2004 as an ad hoc system to coordinate disaster reaction in the midst of the storm in the Indian Ocean.

Shinzo Abe, the then-prime minister of Japan, suggested calling the gathering the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue in 2007. The file did not succeed, however, because many individuals were concerned about upsetting China.

Abe, yet, always gave up on the Quad. The four original Quad places reaffirmed their commitment to the Quad model in soon 2017, on the eve of the ASEAN Summit in Manila.

The Quad gained momentum despite the release of independent push releases outlining specific local objectives. In 2019, they held their second ministerial-level gathering on the outside of the UN General Assembly.

During the Biden-Kishida time, the Quad more institutionalized itself. In March 2021, the Quad officials held their first digital Leaders ‘ Summit. This introduced a move from merely speaking to speaking. They established working organizations on climate change and crucial systems, and they pledged to provide one billion Covid-19 immunizations to the Indo-Pacific.

Although the future US and Japan elections may result in new leadership interactions, the Quad style will most likely survive. The gathering of the main sea governments is not representative of any one management or set of views, according to Mira Rapp-Hooper, senior producer for East Asia and Oceania at the White House, but rather a set of enduring objectives shared by all four countries.

In Japan, the Quad carries both Abe’s and Kishida’s legacy. The LDP is largely supportive of the Quad Agenda and Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy.

In the US, it is likely, if elected president, that Kamala Harris will remain the Biden administration’s method to the Quad. If Donald Trump wins, it is also possible that his administration will continue to support the strategy he supported as chairman in 2017.

Next, in recognition of the growing connection between the Indian and Pacific oceans, his administration changed the name of the US Pacific Command to the US Indo-Pacific Command in 2018. The US Strategic Framework for the Indo-Pacific was eventually released by the Trump presidency in 2018.

Erik Lenhart is a former Deputy Chief of the Mission of the Slovak Republic in Tokyo and graduated from Charles University with an MA in social research.

Michael Tkacik holds a JD from Duke University and a PhD from the University of Maryland. Tkacik’s current research interests include the relevance of China’s fall, China’s actions in the South China Sea, and atomic weapons plan across Asia. He is the head of the School of Honors at Stephen F. Austin State University in Texas and a professor of authorities there.