Commentary: China needs immigrants to escape a âlow fertility trapâ

But changing immigration policy will likely require a change in mindset.

In a recent story by The Economist, the reporter notes that Chinese “officials boast of a single Chinese bloodline dating back thousands of years”. And that taps into a seemingly deep-rooted belief in racial purity held by many leaders in the Chinese Communist Party.

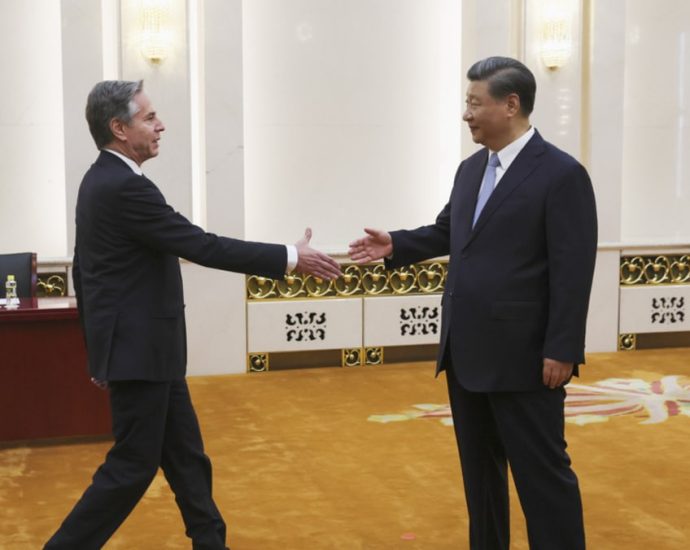

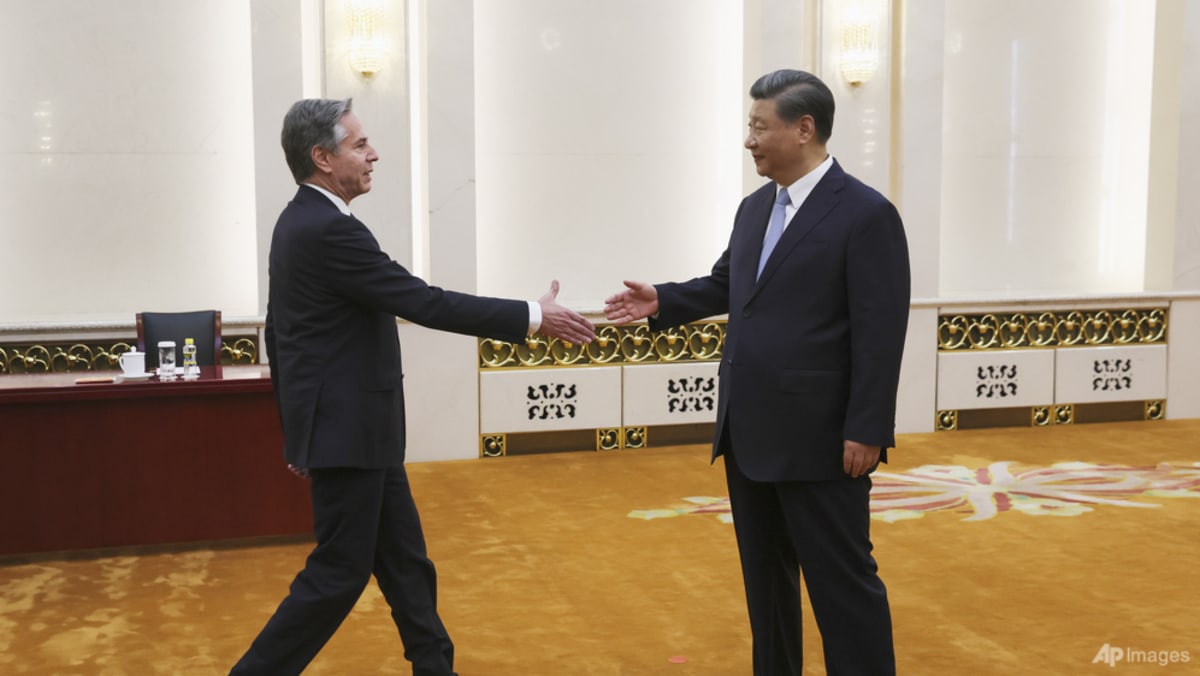

In 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping told former US president Donald Trump: “We people are the original people, black hair, yellow skin, inherited onwards. We call ourselves the descendants of the dragon”.

The best way to maintain this racial purity, many in China believe, is to limit or prohibit migration into China.

But relaxing immigration policy will not only boost numbers, but it will also offset any drop in productivity caused by an ageing population. Immigrants are typically of prime working age and very productive; they also tend to have more babies than native-born residents.

The US and many European countries have relied for decades on international migration to bolster their working-age population.

For immigration to have any reasonable impact in China, the number of people coming into China will need to increase tremendously in the next decade or so – to around 50 million, perhaps higher. Otherwise, in the coming decades, China’s demographic destiny will be one of population losses every year, with more deaths than births, and the country will soon have one of the oldest populations in the world.

Dudley L Poston Jr is Professor of Sociology, Texas A&M University. This commentary first appeared on The Conversation.