Getty Images

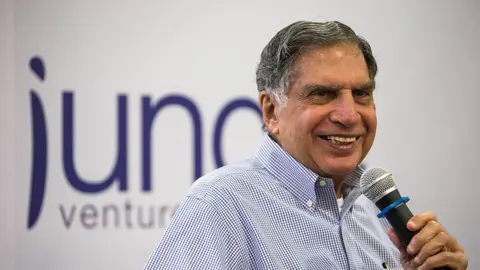

Getty ImagesRatan Tata, the billionaire and former chairman of Tata Group, who passed away at the age of 86, played a significant role in the modernization and globalization of one of India’s oldest company buildings.

His ability to take strong, daring business risks served as the foundation of the salt-to-steel conglomerate, which his forefathers founded 155 years previously, despite India’s liberalization of its economy in the 1990s.

At the turn of the millennium, Tata executed the biggest cross-border merger in American business record- getting Tetley Tea, the country’s second largest maker of teabags. The little Tata party firm that had purchased the classic British brand was three times the size of it.

His party swallowed up big American business giants like the shipbuilder Corus and the luxury car manufacturer Jaguar Land Rover as his ambitions grew just bigger in the years that followed.

Although the acquisitions were n’t always successful, Corus was purchased just before the 2007 global financial crisis, which hampered Tata Steel’s performance for years.

They also had a great symbolic impact, says Mircea Raianu, writer and creator of Tata: The Global Corporation That Built Indian Capitalism. He goes on to say that they “represented the kingdom striking up” when a company from a former colony seized the motherland’s prized possessions, reversing the sneering approach American businessmen had toward the Tata Group a decade before.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesInternational interests

The Tata Group’s view had been “outward-oriented” from the very end, according to Andrea Goldstein, an analyst who published a study in 2008 on the internationalisation of American companies, with a special emphasis on Tata.

As early as in the 1950s, Tata companies operated with foreign partners.

But Ratan Tata was keen to “internationalise in giant strides, not in token, incremental steps”, Ms Goldstein pointed out.

According to Mr. Raianu, his unconventional education in architecture and a ringside view of his family group companies may have contributed to how he considered expanding. But it was the” structural transformation of the group” he steered, that allowed him to execute his vision for a global footprint.

Tata had to fight an extraordinary corporate feud when he assumed the position of chairman of Tata Sons in 1991, which happened to coincide with India’s decision to open up its economy.

By opening the door to a number of” satraps” ( a Persian term for an imperial governor ) at Tata Steel, Tata Motors, and the Taj Group of Hotels, which operated with little corporate oversight from the holding company, he began centralizing increasingly decentralized, domestic-focused operations.

By doing this, he prevented the Tata Group, which had been shielded from foreign competition, from fading into irrelevance as India opened up, as well as enabling him to surround himself with people who could assist him in carrying out his global vision.

He appointed foreigners, non-resident Indians, and executives with connections and networks throughout the management team at both Tata Sons, the holding company, and individual groups within it.

He established the Group Corporate Center ( GCC ) to provide group companies with strategic direction. It provided” M&, A]mergers and acquisitions ] advisory support, helped the group companies to mobilise capital and assessed whether the target company would fit into the Tata’s values”, researchers at the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore wrote in a 2016 paper.

The GCC also provided funding for Tata Motors ‘ well-known acquisitions, including Jaguar Land Rover, which had a significant impact on how the world saw a business that was essentially a tractor manufacturer.

The JLR takeover was widely regarded as “revengeance” on Ford, which mocked Tata Motors in the early 1990s and then received a beating on the deal by Tata Motors. Together, these acquisitions suggested that Indian corporations were “arrived” on the global stage as economic growth rates increased and liberalization reforms were taking off, according to Mr. Raianu.

The$ 12 billion group currently has operations in 100 different nations, with non-Indians making a sizable portion of its total revenues.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe misses

While the Tata Group made significant strides overseas in the early 2000s, domestically the failure of the Tata Nano – launched and marketed as the world’s cheapest car – was a setback for Tata.

This was his most ambitious project, but he had clearly misread India’s consumer market this time.

Brand experts claim that an aspirational India did n’t want to associate with the affordable car tag. And Tata himself eventually admitted that the “poor man’s car” tag was a” stigma” that needed to be undone.

He thought that his company might be able to revive its product, but the Tata Nano was eventually discontinued after sales dropped year over year.

The Tata Group’s succession became a contentious topic as well.

Mr Tata remained far too involved in running the conglomerate after his retirement in 2012, through the “backdoor” of the Tata Trust which owns two-thirds of the stock holding of Tata Sons, the holding company, say experts.

Ratan Tata’s involvement in the succession dispute with [Cyrus ] Mistry undoubtedly tarnished the reputation of the group, according to Mr. Rainu, without blaming him for it.

Following a boardroom coup that sparked a long-running legal battle that the Tatas eventually won, Mistry, who died in a car crash in 2022, was ousted as chairman of Tata in 2016.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA lasting legacy

Tata left his vast empire in a much stronger position both domestically and internationally in spite of the numerous missteps he took in 2012, leaving it much more financially stable.

Along with making significant acquisitions, his effort to modernize the company with a sharp focus on IT has been successful over the years.

When many of his big bets went sour, one high-performing firm, Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), along with JLR carried the “dead weight of other ailing companies”, Mr Raianu says.

TCS is today India’s largest IT services company and the cash cow of the Tata Group, contributing to three-quarters of its revenue.

Around 69 years after the government took control of the airline, the Tata Group also brought back India’s flagship carrier Air India in 2022. Given how expensive it is to operate an airline, Ratan Tata, a trained pilot himself, was a dream come true.

However, the Tatas appear to be more in a position to place significant bets on everything from semiconductor manufacturing to airlines.

Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, it appears that India has clearly adopted a “national champions” policy, which requires a few large conglomerates to be built up and promoted in order to achieve rapid economic growth that spans priority sectors.

The odds are clearly stacked in favor of the Tata Group from this, along with younger industrial groups like Adani.