On Tuesday, Seattle became the first US city to ban caste-based discrimination after a vote by the local council. Ahead of the vote, several South Asians stood in line for hours to share their stories with council members.

Academic Prem Pariyar was one of them. He says he fled to the US from Nepal in 2015 after his family was brutally attacked by a group of upper caste people for speaking up against atrocities.

But that didn’t stop the discrimination he faced because of his caste. Once, he says, he was invited to lunch at a friend’s house in the San Francisco Bay Area in California.

“I was hesitant [to go] as caste dictates where you sit and eat, but I thought it will be different here as people are educated, in a country where human rights are valued,” Mr Pariyar says.

But just as he was about to serve food for himself, he was asked not to touch anything. Instead, someone else handed him a plate of food.

The caste system is one of the oldest forms of surviving social discrimination in South Asian countries, including India and Nepal. In India, Dalits (formerly untouchables) and other lower castes are seen as historically disadvantaged groups and offered constitutional protections in the form of quotas and anti-discriminatory laws.

Dalit activists and academics say such recognition is needed in the West too, especially in the US. Many of them have been working for years towards spreading a similar awareness of caste and its complexities there. That’s why, they say, Seattle adding caste to its anti-discrimination laws is a landmark event.

Mr Pariyar says the incident at his friend’s house reminded him of something from his childhood in Nepal: his teacher spat out the water he gave her after finding out he belonged to a lower caste.

As a student in the US, Mr Pariyar became instrumental in a movement that asked for protection against caste discrimination from California State University (Cal State), the largest public university system in the US. Last year, the university approved a policy change which added caste as a protected category.

In Seattle, Shahira Bangar (name changed) helped mobilise people for the campaign to ban caste discrimination. For her, caste is not just a “Hindu” issue but one that affects most South Asian religions.

She was raised in California by Sikh parents who migrated from the northern Indian state of Punjab. Her father, she says, changed his surname to “avoid being outed as a Dalit” at his workplace. The family also started going to a temple run by Dalits after they were treated “differently” at a large gurdwara attended by upper caste Sikhs.

Ms Bangar says her own experience of discrimination began when she was in high school in California. “I went to my then best friend’s house. Referring to me, her mum said that ‘her family are chamars’ – she said it in a horrible way,” she says. Chamar is a pejorative caste term used to describe Dalits who work with animal hide.

San Francisco Bay Area resident Bhim Narayan Bishwakarma says his attempt to rent a room fell through after the South Asian owner heard his full name – surnames are often indicators of caste. “I could see in his eyes that he really felt uncomfortable,” Mr Bishwakarma says.

After coming up with excuses to opt out of the deal, the landlord finally admitted that his other tenants had threatened to move out if a Dalit person was allowed to stay.

Kanishka Elupula, who is working on caste and class for his PhD at Harvard University, says his South Asian peers have often assumed he belongs to an upper caste because “they don’t think a Dalit would be at Harvard”.

“They are almost convinced and genuinely believe they don’t care about caste, but they practise the same forms of discrimination that protect their privileges as has been done for many years,” he says.

Equality Labs, a civil rights organisation that has extensively documented caste discrimination in the US, is one of many Dalit and civil rights groups which supported the Seattle legislation.

“First Seattle, now the nation!” executive director Thenmozhi Soundararajan said in a text message after the Seattle vote.

But not everyone supports the legislation. Several Indian-American groups had strongly opposed the ordinance before it became a law, arguing that it singled out Indian and South Asian communities for unique legal scrutiny.

Suhag Shukla, co-founder and executive director of the Hindu American Foundation, says that caste discrimination is wrong and violates core Hindu principles.

But he adds that the new law sent a message “that our community, which makes up less than 2% of the population, is so uniquely bigoted that we need a special category under the law to police us, reinforcing xenophobic stereotypes we had hoped the US had moved beyond”.

The group plans to explore legal options. They are currently suing the state of California in a federal court for a “similarly unconstitutional definition of caste” and assisting with a challenge to Cal State’s addition of caste to its non-discrimination policy – they argue that the “addition of caste singles out one community for ethnic profiling and additional policing”.

Nearly 100 organisations and businesses also wrote to the Seattle City Council this week, asking it to oppose the caste ordinance, arguing that the law would violate the civil rights of the South Asian community. Some believe that this could make South Asians less likely to be considered for jobs.

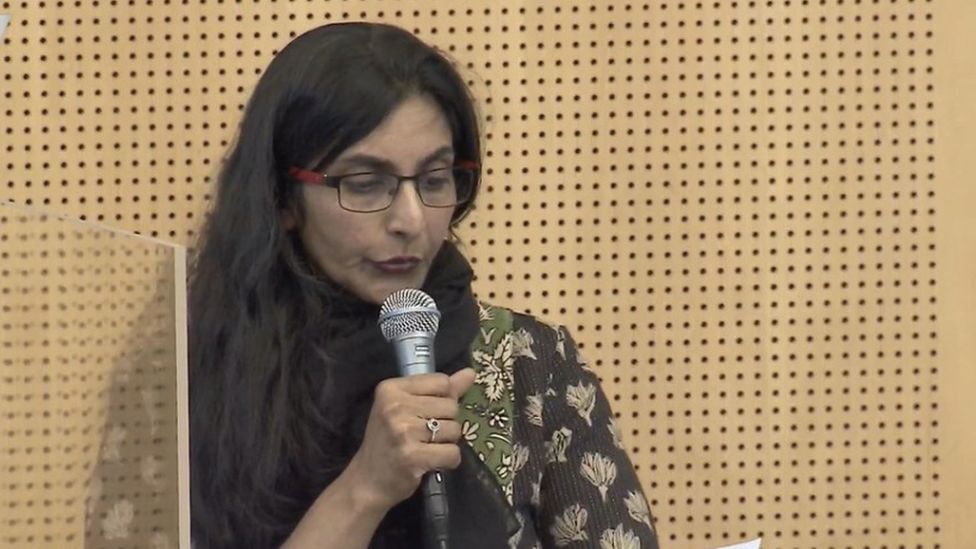

Ahead of the vote, city council member Kshama Sawant, an Indian-American from a Brahmin family who proposed the ordinance, had said that their work had just begun. “This is a truly ground-breaking legislation, it will be a beacon for councils and communities across the country.”

Ms Soundararajan says her organisation is now inundated by calls from people who want to join them.

“Dalits have won the “culture war” with an unprecedented number of South Asians willing to talk about openly about this situation. We are not going back to a caste-less reality.”

Read more India stories from the BBC:

Related Topics

-

-

28 April 2022

-

-

-

11 hours ago

-