Victory City is an epic chronicle of the rise and fall of Vijayanagar (the capital city of the historic southern Indian Vijayanagara empire), which acquires the name “Bisnaga” through ill-fated attempts at pronunciation by a Portuguese traveler.

The story unfolds as a fictional retelling of Bisnaga’s history, premised on the archaeological discovery of the Jayaparajaya, a poem by a writer named Pampa Kampana. Readers are told that its title translates as “Victory and Defeat.”

The unnamed narrator’s voiceovers and alternative versions of stories alert readers to the intersections of memory, memorialization and history. As the narrator explains: “We knew only the ruins that remained, and our memory of its history was ruined as well, by the passage of time, the imperfections of memory.”

Throughout the novel, Rushdie explores the process of writing history – how it is recorded and how significance is apportioned. As Pampa Kampana states: “History is the consequence not only of people’s actions but also their forgetfulness.”

Rushdie is interested in how history is argued over and rewritten in contemporary moments. In particular, he takes aim at the populist exploitation of historical narratives for political gain. We hear that “fictions could be as powerful as histories” and that – paradoxically – “they were no more than make-believe but they created truth”.

Through her poem, Pampa Kampana generates in Bisnaga’s inhabitants a collective stake in the city and the civilization it wants to build. The novel chronicles the fate of the city through successive rulers, who ultimately cause its downfall.

Victory City’s place in Rushdie’s oeuvre

Victory City takes an interesting position in Rushdie’s wider body of work. In some ways it could be read as a companion volume to ideas he explored in The Enchantress of Florence (2008), where a European traveler arrives at the court of the Mughal emperor Akbar, claiming to be the son of a lost Mughal princess, Qara Köz, with magical powers.

Women take a central role in the world-building of both novels – Pampa, like Qara, is an enchantress.

Victory City also marks a return of sorts for Rushdie, who has not set a novel substantially on the Indian subcontinent for over a decade.

At a time of resurgent nationalism, Rushdie’s turn to the historical epic is interesting in its recourse to medieval history and the lineages he develops.

It’s reminiscent of Telugu historical film epics such as Baahubali (2015), or the historical worlds conjured by Hindi filmmakers such as Sanjay Leela Bhansali in Bajirao Mastani (2015), or Ashutosh Gowariker in Jodhaa Akbar (2008).

Victory City – similar to The Enchantress of Florence – showcases Rushdie’s research. The novel includes a bibliography of the works he referenced, including the history of Vijayanagar from the early 14th to the late 16th century.

Rushdie’s training as a historian at Cambridge University resonates in his fiction. There are detailed descriptions of court life, city dwelling and encounters with travelers. There is also an astute sense of the partiality of history and how perspective alters in the different telling and re-telling of the same event.

In this way, Victory City sharpens the reader’s understanding of the writing of history and how it can be used to serve certain agendas.

Rushdie’s plea for tolerance

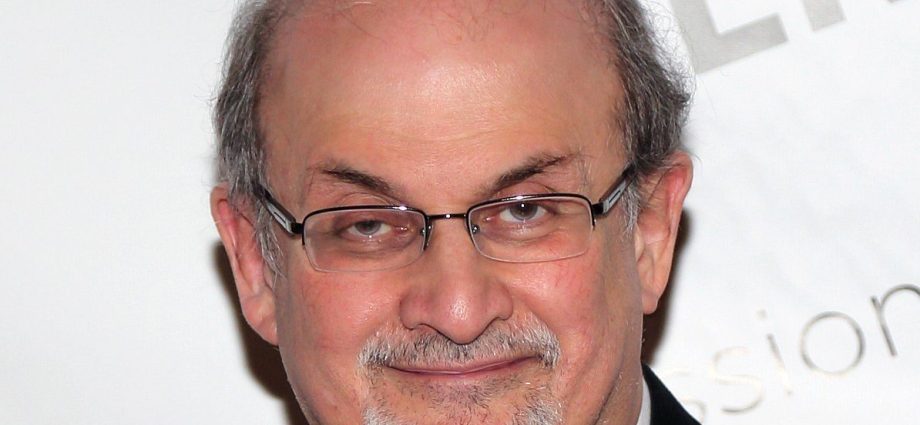

Victory City is Salman Rushdie’s fifteenth novel and the first to be published since he was brutally attacked in August 2022, which left him with life-changing injuries.

Although completed before the attack, the work can be considered a riposte to what Rushdie’s assailant stands for in its appeal to kindness and tolerance. To think about Victory City purely in terms of this incident, however, does Rushdie’s marvelous epic novel an injustice.

Rushdie is an assured storyteller at the height of his powers, revealing once again how important India is as a fount of his imagination.

Victory City is profoundly humanist. Throughout, there is an appeal to justice, respect and equality – and perhaps a prism through which to reflect on how these ideals are increasingly under threat. Rushdie gives us the words and stories with which to defend them.

Florian Stadtler is a lecturer in literature and migration at the University of Bristol.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.