Almost every woman in India has a story of sexual harassment that took place in crowded public spaces – when someone fondled her breasts or pinched her bottom, elbowed her in the chest or rubbed himself against her.

To hit back at their predators, women used whatever they had – for instance, as college students commuting in the overcrowded buses and trams in the eastern city of Kolkata decades ago, my friends and I used our umbrellas.

Many of us also kept our nails long and sharp to scratch straying hands; others used the pointy heels of their stilettos to hit back at men who would take advantage of the crowd to press their penises into our backs.

Many others used a much more effective tool – the ubiquitous safety pin.

Since its invention in 1849, safety pins have been used by women around the world to hold different bits of clothing together, or to deal with a sudden wardrobe malfunction.

They have also been used by women globally to fight back against their harassers, even draw blood.

A few months back, several women in India took to Twitter to confess that they always carried a pin in their handbags or on their person, and that it was their weapon of choice to fight perverts in crowded spaces.

One of them – Deepika Shergill – wrote about an incident when she actually used it to draw blood. It happened on a bus she regularly took to commute to the office, Ms Shergill told the BBC. The incident took place decades ago, but she still remembered the tiniest details.

She was about 20 and her tormenter was in his mid-40s, he always wore a grey safari (a type of two-piece Indian suit popular with government workers) and open-toed sandals, and carried a rectangular leather bag.

“He would always come and stand next to me, lean over, rub his groin in my back, and fall over me each time the driver applied the brakes.”

In those days, she says she was “very timid and didn’t want to draw attention to myself”, so she suffered in silence for months.

But one evening, when he “began masturbating and ejaculated on my shoulder”, she decided it was enough.

“I felt defiled. On reaching home, I showered for a really long time. I didn’t even tell my mother what had happened with me,” she said.

“That night I couldn’t sleep and even thought about quitting my job, but then I started thinking about revenge. I wanted to do bodily harm to him, to hurt him, to deter him from doing this to me ever again.”

The next day, Ms Shergill swapped her flat shoes with stilettos and boarded the bus, armed with a safety pin.

“As soon as he came and stood next to me, I got up from my seat and crushed his toes with my heels. I heard him gasp, and felt a lot of joy. Then I used the pin to puncture his forearm and quickly exited the bus.”

Although she continued to take that bus for another year, she said that was the last she saw of him.

Ms Shergill’s story is shocking, but not rare.

A colleague in her 30s narrated an incident when a man repeatedly tried to grope her on an overnight bus between the southern cities of Cochin and Bengaluru (Bangalore).

“Initially I shook him off, thinking it was accidental,” she said.

But when he continued, she realised that it was deliberate – and the safety pin she had used to keep her scarf in place “saved the day”.

“I pricked him and he withdrew, but he kept trying again and again and I kept trying to prick him back. Finally, he withdrew. I’m happy that I had the safety pin, but I feel silly that I didn’t turn around and slap him,” she says.

“But when I was younger, I was wary that people wouldn’t support me if I raised an alarm,” she adds.

Activists say it is this fear and shame that most women feel that emboldens molesters and makes the problem so widespread.

According to an online survey of 140 Indian cities in 2021, 56% of women reported being sexually harassed on public transport, but only 2% went to the police. A vast majority said they took action themselves or chose to ignore the situation, often moving away because they didn’t want to create a scene, or were worried about escalating the situation.

More than 52% said they had turned down education and job opportunities because of “feelings of insecurity”.

“Fear of sexual violence impacts women’s psyche and mobility more than the actual violence,” says Kalpana Viswanath, who co-founded Safetipin, a social organisation working to make public spaces safe and inclusive for women.

“Women start imposing restrictions on themselves and it denies us equal citizenship with men. It has a much deeper impact on women’s life than the actual act of molestation.”

Ms Viswanath points out that harassment of women is not just an Indian problem, it’s a global issue. A Thomson Reuters Foundation survey of 1,000 women in London, New York, Mexico City, Tokyo and Cairo showed that “transport networks were magnets for sexual predators who used rush-hour crushes to hide behaviour and as an excuse if caught”.

Ms Viswanath says women in Latin America and Africa have told her that they carry safety pins too. And the Smithsonian Magazine reports that in the US, women used hatpins even in the 1900s to stab men who got too close for comfort.

But despite topping several global surveys on the scale of public harassment, India doesn’t seem to recognise it as a big problem.

Ms Viswanath says that’s partly because poor reporting means it doesn’t get reflected in crime statistics, and because of the influence of popular cinema that teaches us that harassment is just a way of wooing women.

In the past few years though, Ms Viswanath says, things have improved in several cities.

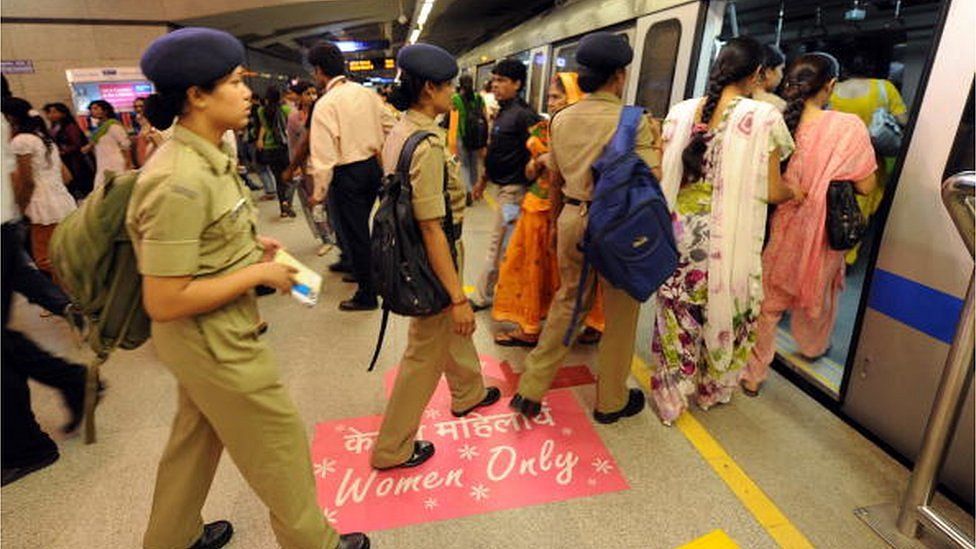

In the capital Delhi, buses have panic buttons and CCTV cameras, more female drivers have been inducted, training sessions have been organised to sensitise drivers and conductors to be more responsive to female passengers, and marshals have been deployed on buses. Police have also launched apps and helpline numbers which women can use to seek help.

But, Ms Viswanath says, it is not always a problem of policing.

“I think the most important solution is that we have to talk more about the issue, there has to be a concerted media campaign that will drill into people what’s acceptable behaviour and what’s not.”

Until that happens, Ms Shergill and my colleague and millions of Indian women will have to keep their safety pins handy.

Read more India stories from the BBC: