June Aochi Berk, then 92 years older, remembers the dread and anxiety she felt 80 years before on Jan. 2, 1945. Due to their Chinese traditions, Berk and her household members were released from the US federal detention center in Rohwer, Arkansas, on military orders. They had been imprisoned for three centuries there.

” We didn’t enjoy the close of our prison, because we were more concerned about our future. Since we had lost all, we didn’t realize what would become of us”, Berk recalls.

The Aochis were one of the roughly 126, 000 people of Chinese ancestry who had been violently held in lonely inland areas as a result of Executive Order 9066, which was issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942.

About 72, 000, or two-thirds, of those incarcerated were, like Berk, American-born people. Their immigrant families were lawful creatures, and the law forbids them from becoming citizens. Based on the assumption that those with the cultural history of an enemy may be hostile to the United States, Rosenevelt’s executive order and following military orders excluded them from the West Coast. The state justified their widespread incarceration as a “military necessity,” without having to file claims against them for each case.

A nonpartisan federal commission concluded in 1983 that the government’s explanation was illogical. It concluded that the prison resulted from “race prejudice, war frenzy and a loss of social leadership”.

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was passed as a result of the commission’s tips. The law, which was signed by President Ronald Reagan, offered surviving prisoners an apology for the unwarranted government actions and key$ 20,000 payments. The prison was a flagrant violation of US constitutional principles, a denial of due procedure, according to this legislation and a number of criminal decisions.

No official, comprehensive information

No one ever managed to track all the individuals who had been subjected to the president’s unlawful actions, which is a crucial component of this horrible and shameful chapter of British history.

The Irei Project: National Monument for the WWII Japanese American Incarceration was launched in 2019 to address this unfairness. The University of Southern California Shinso Ito Center for Chinese Religions and Culture was the initial incubator for this community-based philanthropic project, which aimed to compile the first-ever complete list of the names of each individual detention and concentration camp detention and name.

Taking the job title “irei” from the Japanese word” to console the souls of the dead”, the task was inspired by marble Buddhist monuments that the detainees built while imprisoned in Manzanar, California, and Camp Amache, Colorado, to commemorate those who had died while wrongfully detained.

The term “approximately 120, 000” incarcerees has been frequently used by academics, editors, and the Asian American area because the precise amount of those incarcerated has never been known. The Irei Project aims to verify an exact count and regain respect to each individual who was subject to some legal injustice when the United States authorities reduced them to lifeless enemies by creating an exact list of names.

A few part-time experts on the Irei staff conducted searches of records in the National Archives and other government institutions with the aim of ensuring that no one was left out. Working with Ancestry .com and FamilySearch, Irei researchers have developed innovative approaches and techniques to check names, the locations of detention and, importantly, the correct spelling of titles. More than 100 volunteers assembled and fact-checked the data.

A search through National Archives microfilm records revealed that” Baby Girl Osawa” was the child of a mother who was a resident of the Pomona Assembly Center, a temporary detention facility. As one way to verify that the historical record is accurate, the search turned up some microfilm records. Sadly, the baby lived only a few hours.

This infant is now one of the nearly 6, 000 additional people that the Irei Project has identified as being incarcerated because of avoiding any one out. As of November 2024, the number is 125, 761, as the research continues, the number of documented incarcerees will continue to grow.

The pain of enduring and remembering

Without any means to return to their prewar neighborhood in Hollywood, California, the Aochis went to Denver, Colorado, where friends offered to help them get back on their feet. They and the other prisoners of war armed themselves against prejudice and hostile treatment that had only grown worse during the war, leading to terrorism.

” We just had to focus on restarting our lives, and we had to put the trauma of the incarceration behind us,” Berk said.

For Berk, her fellow incarcerees and their descendants, the Irei Project provides some acknowledgment of the loss of dignity suffered by individuals, families and communities.

” We were taught not to complain”, remembers Berk,” and yet it’s painful now to think about the endless ways in which we were mistreated. Do you know what it’s like to be made to work in a horse stable?

In the years that followed their incarceration, survivors frequently cite how each incarcerated family was made anonymous when their surname was replaced by a family number. Betty Matsuo, incarcerated at 16 and detained in the Stockton Assembly Center and Rohwer Relocation Center, told the congressional commission,” I lost my identity. At that time, I didn’t even have a Social Security number, but the ( War Relocation Authority ) gave me an ID number. That was my identification. I lost my privacy and my dignity”.

For some people, suppressing their rage, resentment, and shame at being treated like criminals when they had not done anything wrong impacted their relationships and relationships. After the war, Mary Tsukamoto, 27, who was imprisoned and was detained in the Fresno Assembly Center and Jerome Relocation Center, felt powerless because the government’s actions were always portrayed as justified, despite the fact that there was never any real reason to suspect the Japanese American community of total disloyalty. She testified before a congressional committee in 1986 that” we have lived within the shadows of this humiliating lie” for decades. Tsukamoto felt that it was crucial to “gain back dignity as a people who can all dream of a ( n)ation that truly upholds the promise of… ( j ) ustice for ( ll )”.

Healing and reconciliation

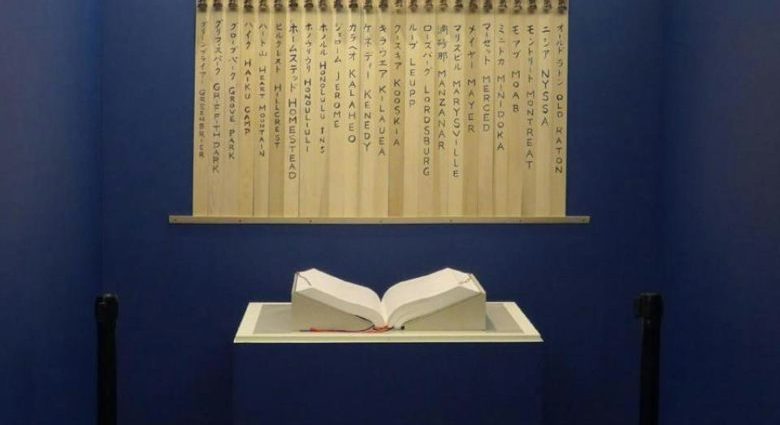

To see the names of those who were incarcerated in a ceremonial book called the Ireichō, which means “record of consoling spirits” in Japanese, is to recognize their suffering. The Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles has housed the Ireich for the past two years.

Anyone who wishes to reserve a blue dot stamp next to the names would be able to use it to honor the Japanese custom of leaving stones at memorial sites. Many surviving prisoners have gathered their friends and family members to stamp names of extended family members, despite the fact that anyone could stamp names without having any relationship to the incarceree.

” The Ireichō has become an iterative form of a monument, drawing visitors as if they are pilgrims to a sacred site”, said Ann Burroughs, the museum’s president and CEO.

Berk was one of the first to stamp the book, choosing to honor her parents, Chujiro Aochi and Kei Aochi. ” My parents set such a resilient example, and by paying this tribute to them, I am able to do something positive to help overcome all of the difficult memories”, Berk explained. Each stamp serves as a small but important step in the community’s effort to reparate the injustices committed by each incarcerated person and re-enter the past.

The Ireich will embark on a national tour in order to stamp each name at least once. The Ireizo, an interactive and searchable online archive, and the Ireihi, light sculptures slated to be installed at eight former World War II concentration camps starting in 2026 are additional components of the Irei Project.

Berk and her partners gathered their five children and eight grandchildren to stamp her name and place additional stamps next to her parents ‘ names on December 1, 2024. She continued,” My children and grandchildren now understand what transpired during the war. We should never forget this period in history, in order for our government to never repeat it and cause any harm to any other person or group.

Susan H. Kamei is an adjunct professor (teaching ) of history and affiliated faculty, USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Cultures, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. At the University of Southern California, Duncan Williams is the professor of religion at Alton Brooks, a professor of American studies, ethnicity, and of East Asian languages and cultures.

This article was republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.