Japan, 2009. It is a sunday in August. A person is spotted lying in the back seats of a rental car in a parking lot in Saitama, a provincial capital, about 30 kilometers north of Tokyo. Yoshiyuki Oide is his brand. It turns out that he’s not having a rapid sleep – he’s dying.

His suicide is primarily thought to be a murder, and the produce is carbon monoxide poisoning. But the officers are no convinced, but they knock on the door of the female Oide had been dating, 35-year-old Kanae Kijima. The research into what had come to be known in the internet as the” Konkatsu killer” situation has just begun. The name derives from konkatsu, meaning relationship looking.

Data from the investigation led to the discovery that Kijima may have killed three people she met on dating websites. Initial reports of suicide were false, but all three murders were later determined to be fabricated. Kijima, who has always maintained her innocence, was found criminal in 2012 on the basis of what was commonly accepted to be anecdotal evidence, mostly due to the court’s agreement. She was sentenced to death. The decision was upheld in successive panders, and she is now on death row awaiting murder.

Kijima’s circumstance was equivalent to that of Chisako Kakehi, who died in prison on December 26, 2024, while under sentence of death. After a court determined that she had entrapped and swindled money from three men ( including her husband ), she had been found guilty of murder and fraud, and she had been sentenced to the death penalty. She had also been found guilty of murder and fraud.

But there was also a unique feature to Kijima’s case. Numerous media outlets have been paying attention to the defendant’s appearance since the beginning rather than the terrible nature of the crime. How could a girl described as “ugly and overweight” maintain to draw these people, according to versions on the same problem in common boards, newspapers, and magazines?

There was a rumor that her success was due to her “homely” traits, which are thought to be the myth of plump women as being cheery, nurturing, and excellent cooks. It was suggested that men may choose for a woman’s comfort and kindness over a fashionable woman’s “air of superiority”.

Someone who has been given the death penalty in Japan typically vanishes from the public attention. However, Kijima kept a site where she detailed her lifestyle and relationships, and continued to blog entries that during and after the trial, perhaps through her attorneys. She continues to write about a variety of topics, including the types of cookies that are available in the confinement facility and the conditions on the death row. She also offers nutritional advice and reflections on the lay judge experiment in Chinese legal procedure.

Kijima pushed up, but the media eagerly mined her posts to dispel myths about gender roles and look. She has used her thoughts to highlight these biases in her analysis of the legal evidence in her sharp criticism of the emphasis on her looks and sex.

Telling the story

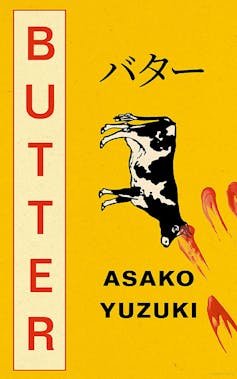

For her book Butter, author Asako Yuzuki used Kijima’s event as inspiration to create a hypothetical tale. A journalist who is covering the case of a lady murderer is sucked into her swirling fascination with butter and generous food, exposing sexism and fat-phobia in Asian society.

Kijima, who has published both a narrative and a debut novel, wrote on her blog to express her profound dissatisfaction with the publication of the book, writing,” What Yuzuki and the editor are doing is nothing short of fraud. They are complicit in murder if they violate external communication rights, not only thieves. I truly believe this book is crass because they continue to use my title without permission.

But, when I interviewed her, artist Yuzuki insisted that, more than the details of the crime, she was interested in the relevance of Kijima’s circumstance, in how the Chinese media frequently sensationalize tales.

Chinese media frequently reflect the viewpoint of strong men. … This discovery was pivotal for me. Prior to that, I hadn’t really considered elections or discrimination in the internet or had much questioned it. However, it hit a muscle when it came to something I adore – eating.

Stereotypes and societal objectives

In her guide, Yuzuki queries some deep-seated Chinese stereotypes – especially around people and eating. She says that the concept of “marriage looking” is also popular in Japan, and women who love cooking are generally labelled as “domestic” or “obedient”.

But, in her practice, people excited about eating is far from obedient. Cooking is potent, in contrast, and a person experienced in the kitchen could just as quickly hurt someone as she could hydrate them. ” There’s a fine line between caring and risky precision”, she told me.

Social media have grown to be a powerful tool for protesters and poets like Yuzuki to interact with others and increase their voice. She has joined other writers in advocating for marginalised groups, including physical immigrants, highlighting the intersectionality of problems such as gender, class, and criminal justice.

Through the writings of writers including Yuzuki and through the Kijima event, the Kijima event offers a strong representation on the impact of political expectations regarding sex and demeanor. Through the facts, Kijima’s blog posts from prison, and through the work of writers including Yuzuki, the Kijima case is a rich source of inspiration. Beyond the question of guilt or innocence, it demonstrates how female criminals are criticized for their deeds as well as for breaking the rules of femininity.

This dual scrutiny coincides with historical biases in Japan, where women who challenge societal norms are frequently portrayed as dangerous outliers. Kijima’s portrayal as an unconventional femme fatale evokes the 19th-century trope of “poison women” – dofuku. This portrays women as obliterating forces that ruin the lives of those who live there.

The death penalty was only used once in 2022 and not at all in 2023, so it appears to be a method of exemplary justice. Many Japanese people believed she had murdered many people while disobeying conventional expectations for femininity.

The case has reinforced the idea that her crimes extended beyond the courtroom to the realm of societal betrayal.

Martina Baradel is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oxford on the Marie Curie.

The Conversation has republished this article under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.