Twenty five years ago, a teenage boy in India was wrongly sentenced to death as an adult for murder. In March, the Supreme Court freed him after confirming that he was a juvenile at the time of the incident.

The BBC’s Soutik Biswas travelled to Jalabsar village in the state of Rajasthan to meet the man, now 41.

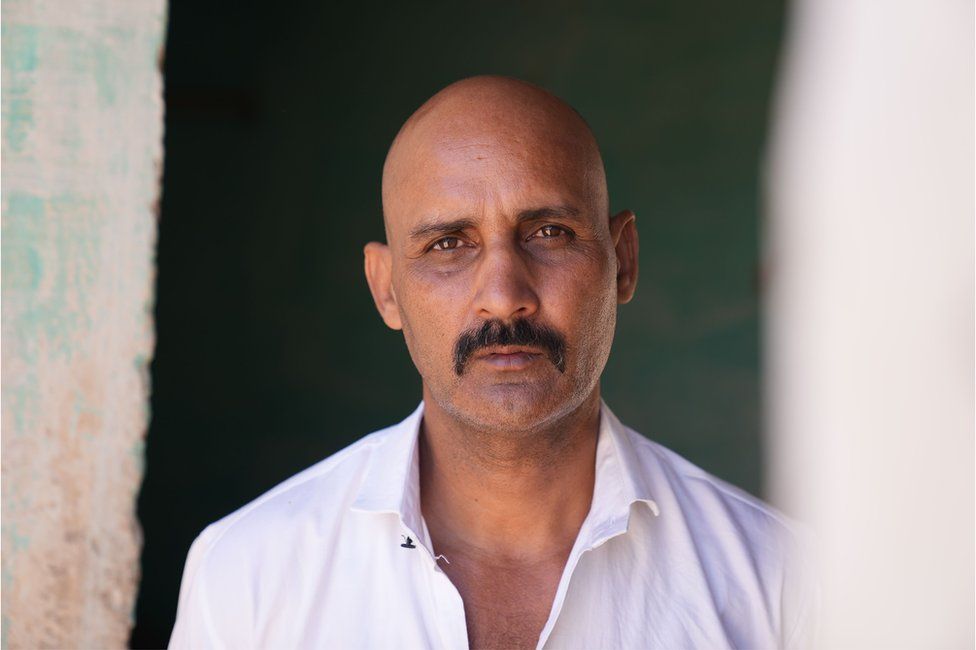

It has been a little over a week since Niranaram Chetanram Chaudhary was freed from the death row in a prison in India’s western city of Nagpur.

He spent much of his 28 years, six months and 23 days in custody – 10,431 days in total – by pacing back and forth in his 12ft by 10ft maximum security cell, reading books, giving exams and trying to prove that he had been found guilty and sentenced before turning 18.

Niranaram was on death row for the 1994 murder of seven people – five women and two children – in the city of Pune. He had been arrested – along with two other men – from his village in Rajasthan. In 1998, he was sentenced to death on the assumption that he was 20.

In March, India’s Supreme Court finally ended Niranaram’s three-decade long ordeal, involving three courts, countless hearings, changing laws, appeals, a mercy petition, age determination tests and a search for his birth date papers.

The judges concluded that Niranaram was 12 years and six months old – or a juvenile – at the time of the offence. (Under Indian laws, a juvenile cannot be sentenced to death, and the maximum punishment for all crimes is three years.)

How had such an egregious miscarriage of justice happened, condemning a teenager to the death row?

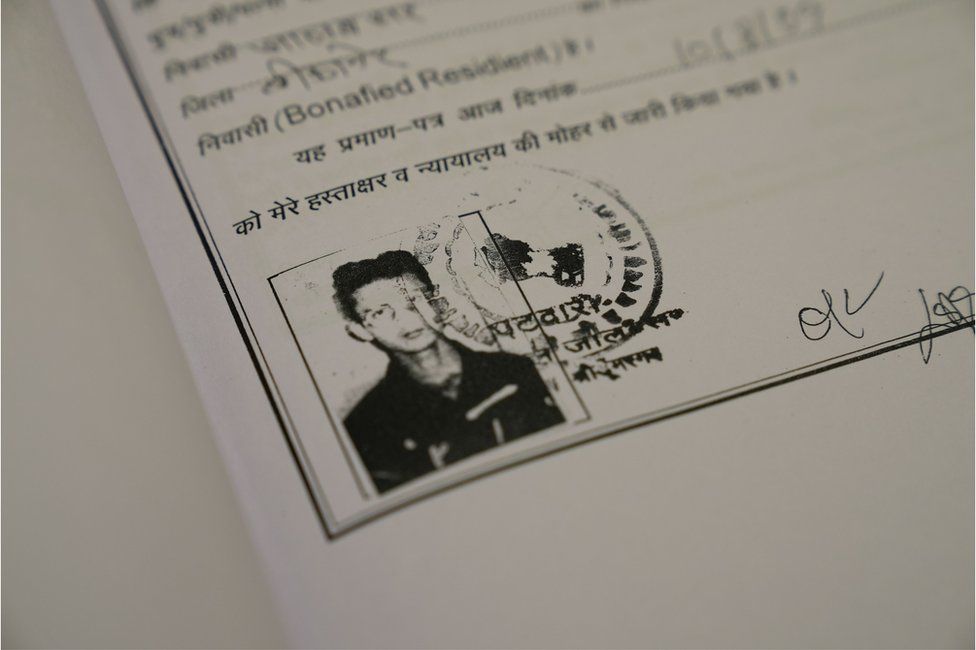

For reasons that are not entirely clear, the police had recorded an incorrect age – and name – when Niranaram was arrested.

His name was wrongly noted as Narayan in a memo prepared by the police at the time of arrest. Nobody quite knows when an erroneous age was first recorded. “His arrest records are very old. The original trial papers didn’t even reach the Supreme Court,” said Shreya Rastogi of Project 39A, a criminal justice programme at Delhi’s National Law University. (Niranaram’s release followed a nine-year-long effort by the programme.)

Surprisingly, the mistake in his birth date and the claim of juvenility was not raised by the courts, prosecutors and defence lawyers until very late in the case – 2018. Absence of birth certificates means many Indians, especially in rural areas, are unaware of their birthdates – Niranaram was one of them.

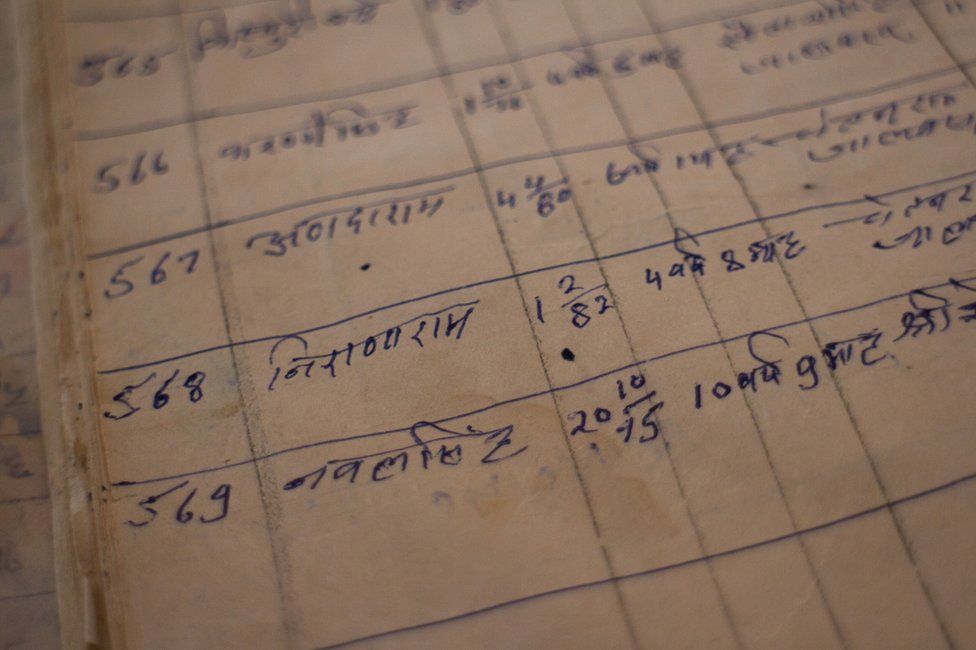

What eventually saved him was an entry in an old register in his village school showing his date of birth as 1 February 1982. There was also a school transfer certificate with dates of his joining and leaving the school and a certificate from the village council head attesting that Narayan and Niranaram were the same person.

“The entire system failed. The prosecutors, defence lawyers, the courts, the investigators. We simply failed to verify how old he was at the time of the incident,” said Ms Rastogi.

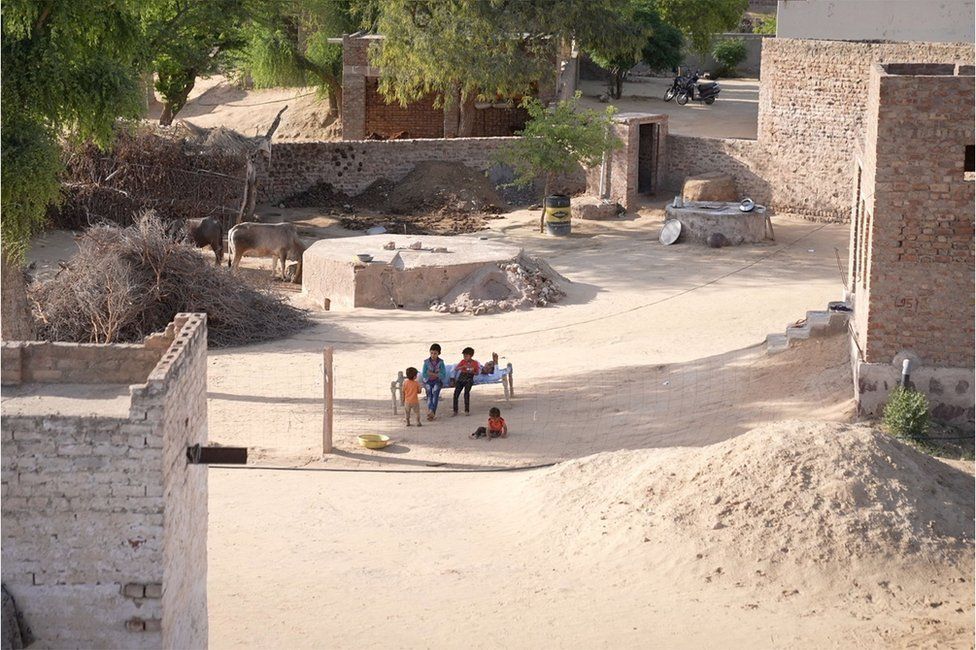

Last week, we drove through a hot and parched landscape of sand flats, scrubs and wilting trees to reach Jalabsar, a village of 600 homes and 3,000 people in Bikaner in Rajasthan. Here Niranaram, born to a farmer father and homemaker mother, had returned to live with his extended family of four brothers, their wives and a dozen nephews.

Set against encroaching dunes and sprawling farms, the village appeared to be reasonably prosperous. The silent, half-deserted streets were flanked by houses covered with satellite dishes and water tanks. The walls of the local school were emblazoned with names of villagers who had donated money and material.

“Why did this happen to me? I lost the prime of my life because of a simple mistake,” Niranaram, a tall and wiry man with sunken eyes, told me.

“Who will compensate for that?”

The state had made no reparations for the mistake.

In 1998, while sentencing Niranaram and a co-accused – who remains in prison, serving a life term – the court said it was a “rarest of the rare case”.

Seven members of a family were knifed to death in a robbery attempt at their home in Pune on 26 August 1994.

According to the victims’ family, one of the accused men worked at their sweet shop in the city and had quit a week before the murders. (He later turned approver – assisting the prosecution – and was released)

The other two accused, including a teenage Niranaram, were unknown to the family. “If their motive was robbery, what was the need of killing everyone [in the house]?” Sanjay Rathi, an anguished family member, had told the Indian Express newspaper in 2015.

Niranaram told me he had run away from home after finishing grade three at the village school.

Why did you run away? I asked.

“I have no memory. I don’t remember the people I ran away with. I landed up in Pune, where I worked in a tailoring shop,” he said.

None of his brothers could recollect why Niranaram ran away.

What about the murders?

“I have no memories of the crime. I have no idea why I was picked up by the police. I remember I was beaten up after I was arrested. When I asked why, the police said something in Marathi language, which I didn’t follow at that time.” (Marathi language is spoken in Maharashtra, where Pune is located)

Did he admit to the crime?

“I don’t remember. But the police made me sign a lot of papers. I was a young boy. I think I was unfairly implicated.”

So are you denying that you committed the crime, I asked him.

“I am not denying or accepting the crime. If my memory clears up, I will be able to say more. I have no memories, I have no flashbacks,” Niranaram said.

While freeing him last month, the Supreme Court mulled whether a 12-year-old boy could “commit such a gruesome crime”.

“But though this factor shocks us, we cannot apply speculation of this nature to cloud our adjudication process. We possess no knowledge of child psychology or criminology to take into account this factor…” the judges said.

Sitting on a tiled floor in a white shirt and beige trousers, Niranaram says he has scant memory of his early days in prison – apart from the “bullying inmates and staff”.

But he remembers his time as inmate number 7,432 in Nagpur jail – he also spent time in a prison in Pune – with some clarity.

No friendships were forged with fellow prisoners because I was “too scared”, he said. He decided to fight isolation by teaching himself. He studied endlessly, wrote exams in his cramped and humid cell and finished school. He picked up a master’s degree in sociology and was preparing for another in political science when he was freed.

He wanted to travel around India if he was released some day, so Niranaram did a six-month course in tourism studies; and another one on ‘Gandhian thoughts’. “Books are your best friend in the prison,” he said.

He read voraciously: Gandhi’s works; popular Indian writers like Chetan Bhagat and Durjoy Datta; and thrillers by Sidney Sheldon. He enjoyed Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. His favourite novel was John Grisham’s The Confession, a legal thriller which he felt mirrored his own fate.

Niranaram said his only contact with the world outside were a couple of English newspapers. He read them from the first page to the last, and when he spotted a picture of Vin Diesel in one of them, he shaved off his hair. He also read about the war in Ukraine. “It shows that today’s world (is) facing lack of globally acceptable leadership, which bring both nations together for a dialogue,” he wrote in a letter from the prison to Ms Rastogi.

“You read and you write and then you get bored also,” he said.

Niranaram began learning languages. He picked up Marathi, Hindi and Punjabi and was preparing to learn Malayalam. But he forgot his own mother tongue, a dialect spoken in Rajasthan.

The night before her long-lost son returned home, his seventy-something mother joined the celebrations by dancing to music blared by a DJ from a rented pickup truck with towering speakers. But when Anni Devi finally came to face to face with Niranaram, tears flowed – and both could not understand what the other was saying. (Niranaram’s father died in 2019.)

“We just stared at each other. She had changed so much,” Niranaram said.

When Niranaram left the prison in late March, he realised “how much India had changed”.

“There were new cars on the road, people wore stylish clothes, the roads were good,” he smiled. “There were young people speeding on Hayabusa bikes which I had thought only film stars could afford. It was a changed country.”

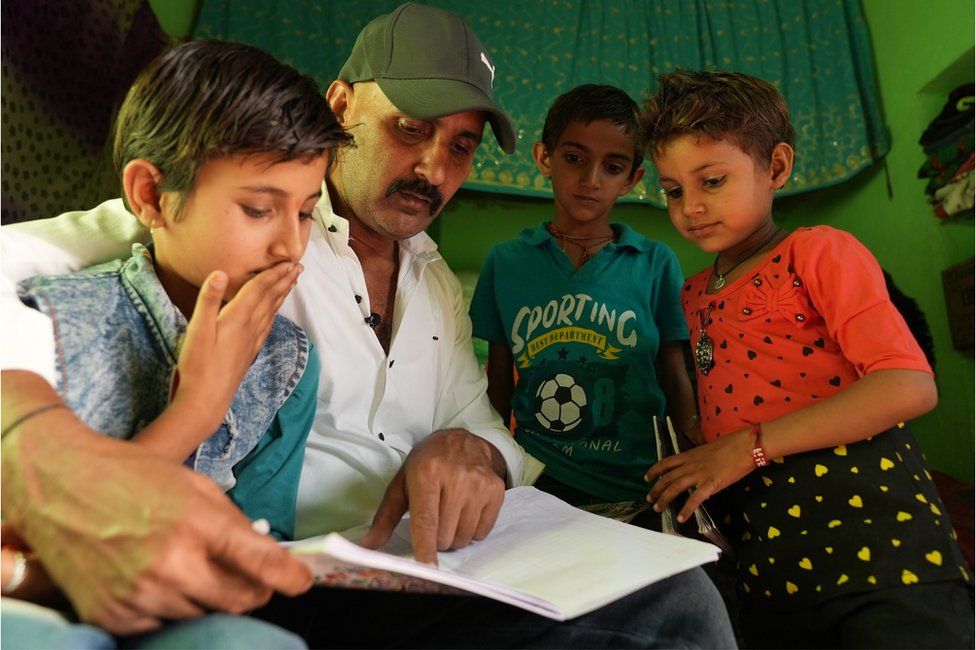

After returning home, language has become Niranaram’s main barrier to socialising. He now speaks Marathi, English and Hindi. But his family and other villagers don’t speak or understand the first two, and struggle with the third. Every day, mother and son spend some time looking at each other and communicating through a translator, usually a young nephew who understands Hindi.

“I feel like a stranger in my own home sometimes,” Niranaram said.

Negotiating people and spaces is another problem. “I am always afraid of colliding with people in public spaces. I am used to prisons and small spaces. The grinding isolation of death row makes you socially inept. I have to be careful, I have to start learning how to live life as a free man,” he said.

Niranaram said he “did not know” how to interact with people, especially women. “I don’t know how to behave and talk with women. How do I tell someone to teach me how to talk to women? I have to always think twice before interacting.”

But he wants to get started with life. His family has given him a mobile phone, which he’s learning how to use. His nephews have opened Facebook and WhatsApp accounts for him. His brothers work on the 100 acres of family farms which grow wheat, mustard and pulses. But Niranaram wants to study law and do social work, helping other prisoners facing similar fates.

For the moment Niranaram is an “attraction” in his village, as his nephew Raju Chaudhary said. “Hundreds of people, including relatives, land up every day to see the man who has returned from death row.”

Niranaram lives in a single room in one of his brother’s homes, teaching English to his nephews. He said it would take time for him to get used to the “fast ways of the free world” compared with the “slow pace” of prisons.

“I am dangling between the past and the future. I am happy I am free. I feel tense about what lies ahead. It’s a strange mix of emotions.”

Photographs and additional reporting by Antariksh Jain

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more by Soutik Biswas

- Their son vanished – then an imposter took over for 41 years

- The Indian ‘germ murder’ that gripped the world

- When a cobra became a murder weapon in India

- Five murders, six men and 16 years of stolen lives

- A kidnapped girl, a skeleton and a house of memories

- How an Indian woman tracked down her daughter’s ‘dead’ rapist