The road to forming a government is never easy, is a saying steeped in harsh political reality, which the Move Forward Party (MFP) is currently finding out for itself.

The party, which earned a spectacular victory in the May 14 election and secured the coveted biggest party accolade, has also learned first-hand that winning a general election precedes the next difficult task of forming a coalition government.

Success depends on the right blend of patience, tact, diplomacy, and manoeuvring being applied.

But building a coalition will only come to fruition if MFP leader, Pita Limjaroenrat, overcomes perhaps the party’s hardest hurdle — collecting votes from its nemesis, the Senate.

Pressure from MFP supporters is also building on parties across the political divide as well as senators to elect Mr Pita as the next prime minister.

Srettha Thavisin, himself a Pheu Thai Party prime ministerial candidate, joined the chorus of support for Mr Pita to be elected premier.

If enough parties — which must also include those from across the political divide from the MFP and Pheu Thai — back Mr Pita in the parliamentary vote, they could cut out the Senate who must otherwise be brought in to co-elect a prime minister.

Co-election will be the order of the day if Mr Pita’s camp fails to muster enough votes from among MPs to get his nomination approved.

However, critics said the premiership vote issue should not be treated simplistically or superficially. Looking through rose-tinted glasses would only produce a distorted reality, they warned.

Nuttaa “Bow” Mahattana, an activist and political commentator, said on Facebook that there is a great deal more to the Pita premiership vote than meets the eye.

She said one should stay true to the principle of electing a prime minister. The concept of picking Mr Pita is, in essence, synonymous with an expression of intent by lawmakers that they favour the MFP’s way of directing the country’s economic, social and political affairs as pledged during the election campaign.

It is totally separate from the issue of whether or not the Senate should be drawn into co-electing Mr Pita as premier.

Political parties which view Mr Pita as the wrong fit for prime minister have every right not to vote for him in parliament as they have their constituents to answer to. These constituents elected the respective party candidates primarily because they found their campaign policies struck a chord with them.

If these constituents had preferred the MFP’s poll mantras and way of conducting politics, they would have chosen that party instead, according to Ms Nuttaa.

There is no such thing as a “price to pay” by parties which decide to vote against or abstain from voting for Mr Pita, as some political elements were trying to mislead people into believing.

Already, some parties have publicly denounced the Pita-for-premier pressure being piled on them.

Former House Speaker Chuan Leekpai, also a former leader of the Democrat Party, said: “Don’t expect others to think the same way. Each party can think for itself.”

Chartthaipattana Party chief adviser, Kanchana Silpa-archa, took to her Facebook to say the party was free to act as it chooses and that the pressure was completely uncalled for.

“We have a mind of our own and follow our own stance. You cannot dominate us,” she said, apparently referring to the MFP.

“You are trying to spin the heads of social media users, something which you are superbly skilled at doing, so they will, in turn, heap the pressure on us. Your version of democracy is the real dictator,” she continued.

Meanwhile, Ms Nuttaa posted another Facebook message, warning MFP supporters against feeling entitled over the Pita premiership issue.

She likened politics to a journey through an obstacle course. Each obstacle needs a different method to overcome it.

“One may have comfortably managed to beat the obstacles so far by means of driving a wedge, taunting or disparaging others and been showered with gold stars for doing it.

“Now, the next obstacle [understood to be the government formation] requires a special tool called friends to move past it. How does one achieve this considering that one has managed to ditch all one’s friends in the world in order to get here?” she said.

She was thought to be directing her comments at the MFP, which has been chided for having turned against several parties, particularly medium-sized ones that are crucial building blocks for piecing together a government.

After the general election, all medium-sized parties are now in a bloc which stands opposed to the MFP-led alliance.

According to observers, the MFP may count itself lucky still being on speaking terms with Pheu Thai. However, even if the MFP succeeds in forging a coalition with Pheu Thai in it, the latter is expected to drive a ridiculously hard bargain to get its way on how many and what cabinet posts it gets.

Chances are Pheu Thai will walk away with more than its fair share of the A-grade ministries without a whimper from the MFP, the observers said.

Defusing a political bomb

The spotlight this week has been on the 23-point memorandum of understanding (MoU) signed by eight coalition parties to lay the foundations for forming a coalition government.

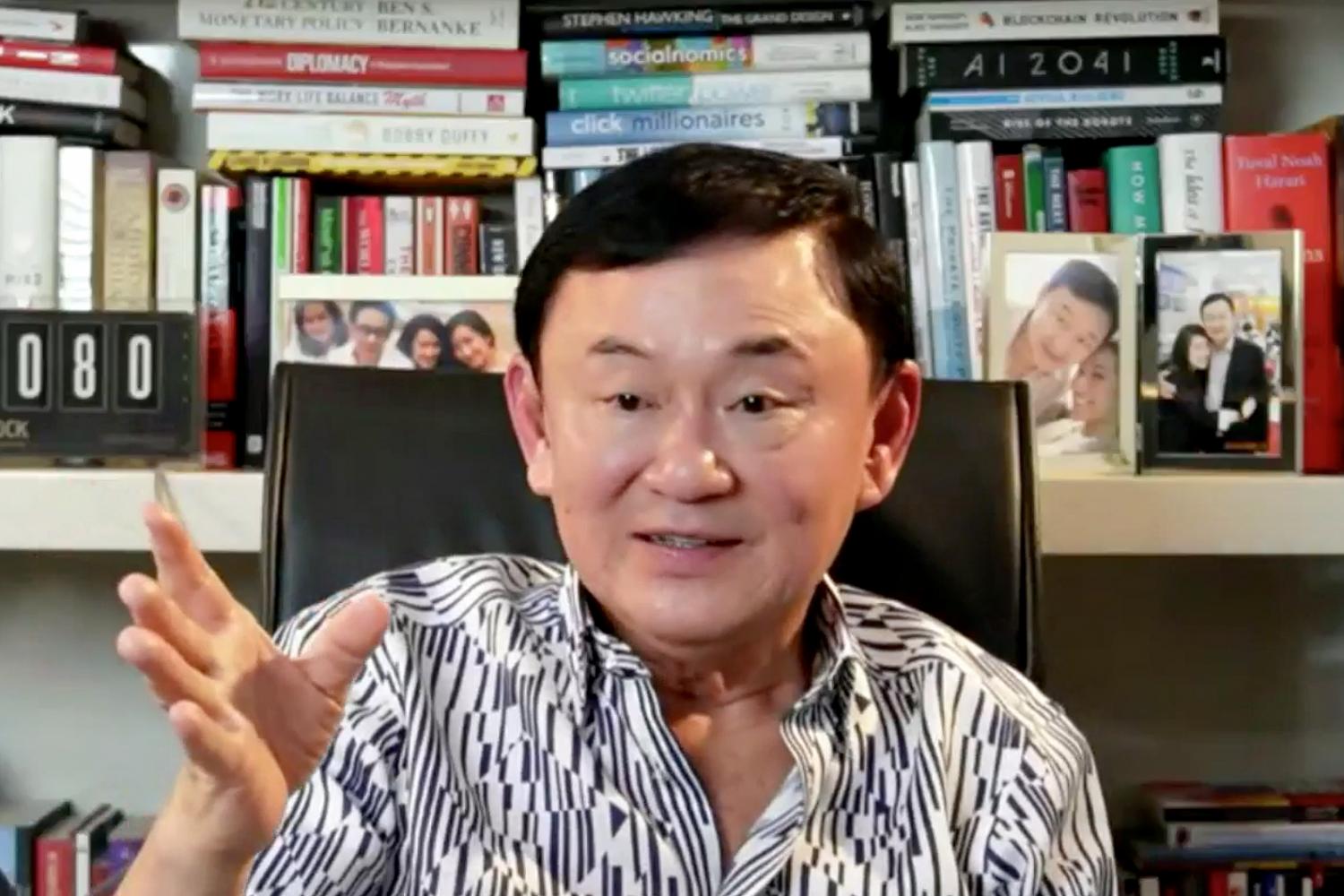

Thaksin: Plans to return in July

Missing from the agreed agenda were two major Move Forward Party (MFP) campaign pledges — amending Section 112 of the Criminal Code and enacting an amnesty law for political offenders, with the latter receiving less attention than the former.

The amnesty proposal was included in the original version of the MoU sent to the seven prospective coalition partners, according to a Pheu Thai source.

It was to cover political cases dating back to the 2006 military coup, except those related to corruption and causing deaths.

However, the issue is a definite no-no for Pheu Thai, which insisted it must not be contained in the MoU.

The party was strongly opposed to having it in the document because the matter could have been interpreted as Pheu Thai’s own bid to help bring former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra home.

Thaksin was ousted in the 2006 putsch led by then-army chief Gen Sonthi Boonyaratglin. He fled the country in 2008, shortly before his conviction by the Supreme Court on a charge of abusing his power as prime minister by helping his then-wife, Khunying Potjaman Na Pombejra, buy prime land in Bangkok at a discount.

After winning the 2011 polls, Pheu Thai pushed through an amnesty law in parliament. The move, seen as a legal whitewash for Thaksin, triggered prolonged street protests that culminated in the 2014 coup.

According to the Pheu Thai source, Thaksin announced plans to return to Thailand this year, possibly before July 26, his 74th birthday, and was not looking for an amnesty.

In an interview before the May 14 election, he said he was ready to serve his prison term, provided he was allowed to spend the rest of his life with his family, regardless of the results of the polls.

So it was highly likely that Pheu Thai would become the target of criticism if the amnesty issue appeared on the MoU.

It would also appear unfair if the proposed amnesty were seen helping MFP supporters and members charged for their roles in anti-government protests, according to the Pheu Thai source.

“Pheu Thai is not a beneficiary of the amnesty proposal. It shouldn’t take that kind of criticism,” said the source.

Several red-shirt protesters aligned with Pheu Thai are either doing time or have served their sentences, the source explained.

The core figures have scattered among other parties, with Jatuporn Prompan and Seksakol Attha-wong becoming Pheu Thai’s most vocal critics.

Pheu Thai’s objection to this thorny issue led to the revision of the MoU which was seen by the media before this week’s signing.

It said all coalition partners would work together to push for the administration of justice in “cases involving expressions of political views” in parliament to forge national unity.

Still, the words were seen as an attempt to seek amnesty for anti-government protesters charged with sedition, violating the computer crime law, breaching the emergency decree and lese majeste.

Among those expected to benefit from this were MFP candidates Piyarat “Toto” Chongthep and Chonticha Jangrew, who won House seats in Bangkok and Pathum Thani, respectively, as well as Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit and Piyabutr Saengkanokkul, who are co-founders of the Progressive Movement and the MFP’s campaign assistants.

The coalition partners were said to have negotiated up to the wire before the amnesty proposal was removed from the final version of the MoU to avoid any obstacles that could jeopardise forming a coalition government.

However, the MoU has left room for coalition partners to individually push their own policies through legislative and executive channels on the condition that they do not contradict the document.

According to observers, an amnesty plan is a process that cannot be rushed or driven by a hidden agenda and past governments underwent a lengthy process of fact-gathering and establishing before making a move.

Like the MFP’s effort to rectify the ultra-sensitive Section 112 — the lese majeste law — the amnesty issue would be a potential timebomb if the MFP decided to unilaterally table the draft law in parliament, according to observers.