In 2019, Yoo Seung-gyu stepped out of his studio apartment for the first time in five years.

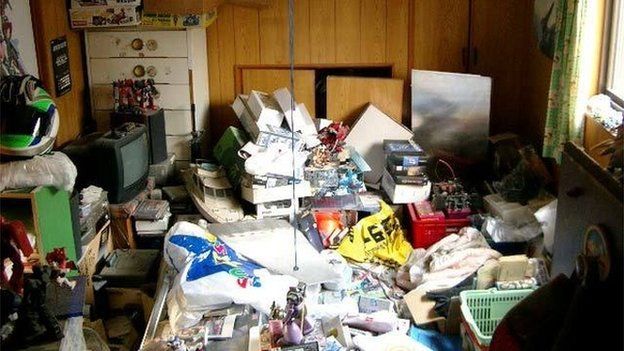

The 30-year-old first cleaned up his “messy apartment” with his brother. And then he went out to sea for a fishing expedition, with fellow recluses he had met through a non-profit organisation.

“It was a weird feeling to be at sea but at the same time very refreshing after the reclusion. It felt unreal, but surely I was there. I was existing,” Mr Yoo said.

A growing number of young South Koreans are choosing to isolate themselves, withdrawing fully from a society that exacts a high price for failing to conform to expectations.

These recluses are known as hikikomori, a term first coined in Japan in the 1990s to describe severe social withdrawal amongst adolescents and young adults.

In South Korea, which is battling the world’s lowest fertility rate and declining productivity, this has become a serious concern. So much so that authorities are offering young recluses who meet a certain income threshold a monthly stipend to coax them out of their homes.

Those between nine and 24 years of age from lower-income families can receive up to 650,000 won ($490; £390) as a monthly living allowance. They can also apply for subsidies for a raft of services, including health, education, counselling, legal services, cultural activities and even “correction of appearance and scars”.

These incentives aim to “enable reclusive youth to recover their daily lives and reintegrate into society”, South Korea’s Ministry of Gender Equality and Family said.

It defines reclusive youths as “adolescents who have been living in a confined space for an extended period of time, cut off from the outside world, and have significant difficulty living a normal life”.

But throwing money at the issue will not make it go away, say young people who have isolated themselves.

Mr Yoo now runs a company that supports reclusive youths called Not Scary – a far cry from the days of not leaving his room even to use the washroom.

But his journey out of reclusion has been full of ups and downs. He first withdrew from the outside world when he was 19, came out of it for two years to serve mandatory military service, and then isolated himself again for two years after that.

Park Tae-hong, another former recluse, said self-isolation can be “comforting” to some people. “When you try new things, it’s exciting but at the same time, you need to endure some level of fatigue and anxiety. But when you are just in your room, you don’t have to feel that. However, it’s not good in a long term,” the 34-year-old said.

About 340,000 people aged 19 to 39 in the country – or 3% of this age group – are considered lonely or isolated, according to the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs.

Research has also shown a growing proportion of single-member households in South Korea, accounting for about a third of entire family units in 2022. At the same time, the number of people who died “lonely deaths” in the country has risen.

But money, or the lack of it, is not what is driving young people into reclusion.

“They come from varied financial backgrounds,” said Mr Park. “I wonder why the government connects reclusion with financial status. Not every reclusive youth is having financial difficulties.”

“Individuals who desperately need money may be forced to adapt to society. There are just a lot of different cases,” he added.

Both him and Mr Yoo, for instance, were financially supported by their parents when they were in reclusion.

What is common among young recluses is the belief they they haven’t lived up to society’s – or their families’ – standards of success. Some feel like misfits because they are are not pursuing conventional career paths, while others may have been criticised for poor academic scores.

Mr Yoo said he went to university because his father wanted him to but quit after a month.

“Going to school made me feel ashamed. Why couldn’t I have the freedom to choose [my course of study]? I felt very miserable,” he said. He also never felt he could talk to his parents about this.

“The ‘culture’ of shame in Korea makes it more difficult for recluses to talk about their problems,” Mr Yoo said. “One day, I just concluded that my life is wrong, and started to isolate.”

While in isolation, he wouldn’t even go to the washroom because he did not want to see his family.

For Mr Park, social pressure was made worse by a strained relationship with this family.

“My mother and father fought often since I was a kid. It also affected my life in school – school in Korea can sometimes be very rough, and I found it difficult. I was not able to take care of myself,” Mr Park said.

He started therapy in 2018 when he was 28, and is now gradually building a social life again.

Young people in South Korea feel “oppressed” because society expects people to be a certain way by a certain age, said Kim Soo Jin, a senior manager at Seed:s, which also specialises in programmes for hikikomori.

“When they can’t live up to these expectations, they think ‘I failed’, ‘I’m too late for this’ – this kind of social atmosphere depresses their self-esteem and may eventually cut them off from society,” she added.

Seed:s runs a physical space dubbed the “mole tunnel”, where recluses can go to rest, have quiet time and seek counselling. Their programmes are open to all everyone, regardless of their income level.

A society where young people can find a greater variety of jobs and education opportunities would be more welcoming to reclusive individuals, Ms Kim said.

“Reclusive youths want a workplace where they can think ‘Ah, I can do this much, it’s not that difficult. I think I can learn more here and then enter the real world’,” she said.

Mr Park too hopes that one day Korean society can be more receptive to young people with interests that are off the beaten track.

“Right now we just force them to study. It’s too uniform. We need to give young people the freedom to find things they like and are good at,” he said.

The living allowances may be a “first step” in addressing the problem, but youth workers say the money can be put to better use. They believe funding organisations and programmes that target reclusive youths, by offering them counselling or jobs training, will have wider impact.

“The next step should be to prepare free, high-quality national programmes for reclusive youths. Right now, there are very limited numbers of programmes and centres where reclusive youth can participate in and feel a sense of belonging,” said Kim Hye Won, chief director of PIE for Youth, an organisation that offers different programmes for reclusive youths and their caregivers.

Still, she is heartened that the South Korean government is trying to tackle the problem at adolescence.

“It’s nice to see that [the new measures] focus on teenagers. I think adolescence is the golden time to prevent reclusion, because most adolescents are part of a community, like school. After that, it becomes very difficult to find these people.”

Mr Yoo said he emerged from isolation gradually, and only after he met former recluses through a now-defunct rehabilitation group called K2 International.

“Once I got help from others, I started to realise that this is not just my own problem but the society’s problem,” he said.

“And finally I was able to get out of reclusion slowly.”

Related Topics

-

-

18 July 2013

-