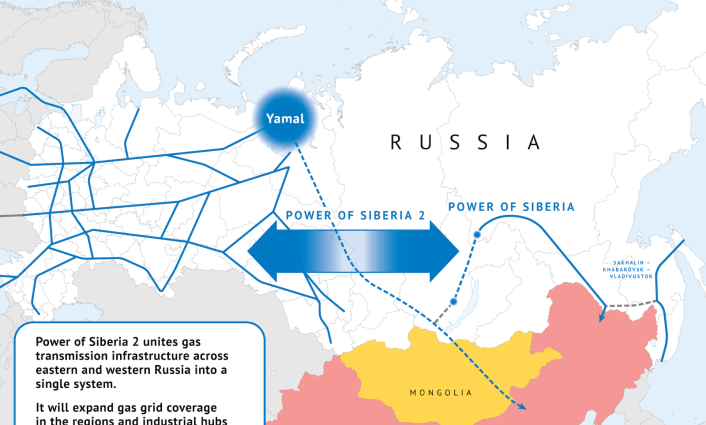

The Power of Siberia-2 (PoS2) gas pipeline has the potential to transform Northeast Asian energy security dynamics, provided Moscow and Beijing agree to its specific terms. With a predicted annual transport capacity of around 50 billion cubic meters of gas, the pipeline’s construction will increase the natural gas supply to China and Asia.

This new source of natural gas will help states diversify their energy portfolios and potentially enable a faster transition away from coal. The pipeline’s construction and maintenance will generate thousands of new jobs across the region and billions of dollars in revenue.

While China is the clear winner from this new source of stable supply at a bargain price, Mongolia will also see socio-economic and strategic benefits.

Some observers have cautioned Ulaanbaatar against working with Russia and China on ideological and strategic grounds. But a cost-benefit analysis suggests that Mongolia has far more to gain than to lose from its potential intermediary role in the project.

Economically, Mongolia expects the PoS2 to contribute up to US$1 billion a year in transit fees to the country’s revenue, create employment, facilitate economic diversification and accelerate its energy transition away from coal. All these developments are necessary conditions for Mongolia’s sustainable growth.

Mongolia is a developing economy with an average per capita income of just over US$4,500, an underemployment rate of more than 12% and an overdependence on resource extraction. Such an economic windfall will have substantial implications for Mongolia’s development.

On energy, Mongolia’s ability to import natural gas through the PoS2 pipeline will help it transition more rapidly away from coal. Mongolia uses coal for 85% of its energy supply and relies on Soviet-era coal-fired combined heat and power plants (CHPs) to service its main cities.

These outdated coal CHPs create heavy air pollution during the winter and directly impact the quality of life of Mongolia’s urban residents.

While Mongolia must invest in solar and wind power in the long term, natural gas offers a short- to medium-term means to reduce coal use. It also offers a long-term means to offset intermittency in renewable energy supply.

Environmentally, the PoS2 could have a positive impact on Mongolia’s overall carbon footprint. While environmental groups have criticized Mongolia’s decision to replace one fossil fuel with another, such criticism is misplaced.

Natural gas produces about half as much carbon dioxide as coal when burned and produces far fewer harmful pollutants, such as sulfur dioxide and particulate matter.

Just as many Asian economies see the transition away from fossil fuels as an incremental process — one that is predicated on moving from coal to cleaner alternatives — so has the Mongolian government prioritized short-term solutions over a long-term fix. In this respect, Ulaanbaatar has rightfully avoided the issue of letting the perfect get in the way of the good.

These are the fundamental considerations — economic, energy and environmental security — that should and do inform Ulaanbaatar’s decision on participating in the PoS2 project. It is not the geopolitical “turn of the screws” as some analysts have suggested.

One finds little — if any — reference to perceived coercion from Russia and China in Mongolian-language writings on the PoS2. Mongolian analysts largely view the PoS2 as a strategic windfall — one that raises the country’s status within Northeast Asia and with Russia and China.

But Mongolia should still try to mitigate any potential risks associated with the PoS2 project. Ulaanbaatar can work closely with regional organizations like the Asian Development Bank to ensure transparency and accountability throughout the tender and construction processes.

Mongolian leadership can also adhere to international best practices in environmental impact mitigation and take measures to ensure that the country has the proper energy infrastructure in place to benefit from gas imports when the time comes.

Fortunately, Mongolia can use much of the same energy infrastructure for natural gas that it needs for other renewable gaseous fuels. This means that investment in gas infrastructure now will help integrate renewable energy sources into the country’s energy grid later.

Mongolia can also de-risk the PoS2’s potential contribution to strategic vulnerability through a foreign policy predicated on omni-enmeshment and balance of influence. This means maintaining ties with both Russia and China to avoid dependency on either – a strategy Mongolia and other Central Asian states have successfully used for decades.

For states like Japan, South Korea and the United States — all having vested interests in Mongolia’s strategic autonomy — this means furthering cooperation through operations and dialogue designed to bolster a stable regional order.

While these mitigation efforts should alleviate whatever residual concern remains among analysts, they can also be seen as direct benefits of Mongolia’s involvement in the PoS2 project.

The more Mongolia integrates itself into Asia’s energy networks, the more it gains in strategic value across the region, such as in the US Seize the Initiative strategy.

Ulaanbaatar should not shy away from such opportunities because of potential downsides. It should instead run towards them.

Jeffrey Reeves is Practice Lead, Asia, with Onyx Strategic Insights.

This article was originally published by East Asia Forum and is republished under a Creative Commons license.