The cheers could be heard in Judy Taguiwalo’s jail cell, where she sat clutching her infant daughter.

It was 25 February 1986 and millions were marching to oust Ferdinand Marcos Sr, the authoritarian leader of the Philippines. His defence minister, Juan Ponce Enrile, had defected and brought with him a large faction of the military. It turned the tide and paved the way for the restoration of democracy.

But 37 years later, as Filipinos march through the streets to commemorate that anniversary, Ms Taguiwalo says her worst fears have been realised. Marcos Sr’s son, “Bongbong” Marcos, has become president and Mr Enrile – once on the side of the People’s Power revolt – is now a key adviser to the new leader.

With the deft use of social media, Marcos Jr has recast his father’s reign as a golden age for peace and infrastructure, dismissing the record of human rights abuses and corruption as an unfair vilification of the family.

“I feel angry at the injustice of it all,” says Ms Taguiwalo, now 73. “It makes me really sad.”

She and Mr Enrile are both survivors of the Philippines’ People Power revolt – but they tell very different stories of the movement’s legacy.

It began as a series of protests in late February in 1986, culminating in what is now a historic march on Manila’s ESDA highway.

Protesters wanted an end to a 20-year dictatorship during which thousands of opposition leaders, students, activists and dissidents disappeared or faced torture. Marcos Sr and his flamboyant wife Imelda also stole billions of dollars from the nation’s coffers, according to a government anti-graft body.

Ms Taguiwalo was a political prisoner. She says she was made to sit on a block of ice until she was numb, and that bullets were stuck between her fingers while her hands were squeezed. She gave birth in prison, and mother and child were released only after Marcos Sr was exiled to Hawaii and Corazon Aquino was sworn in as president.

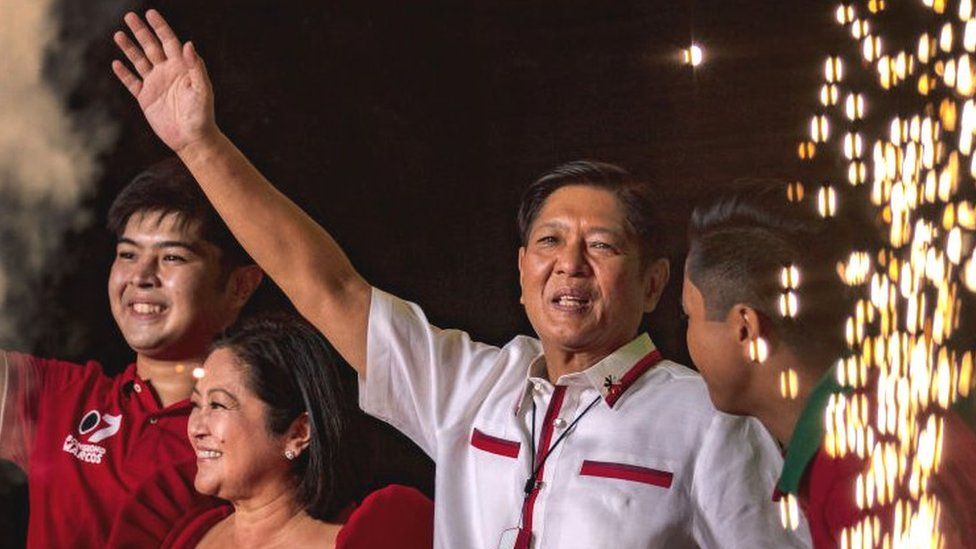

Decades later, the Marcoses have re-established themselves, with Marcos Jr winning the presidency in May 2022 by the highest margin in the country’s history.

Ms Taguiwalo says their return is down to the revolt’s unrealised promise of a better life for Filipinos: “Millions are still poor while billionaires are getting richer. That disillusionment is the major reason.”

Mr Enrile’s political survival is a case in point.

Mrs Aquino retained him as defence chief, giving him a springboard to get elected to parliament for decades. He held on to power until 2019, despite being implicated in failed uprisings under two presidents, including Mrs Aquino.

Even now he serves as Marcos Jr’s chief political adviser, with the hatchet from the People Power revolt long buried. He has also outlived nearly all of the revolution’s main characters.

But he is “not doing anything that’s not ordinary in Philippine politics,” says Jean Encinas-Franco, a political science professor at the University of the Philippines.

Enrile’s advantage was his stature as a leader in the People Power uprising, she says. And that gave him a platform to branch out to various government positions in the nearly four decades that followed.

He turned 99 earlier this month. Marcos Jr wished him congratulations on Facebook, addressing him in Ilocano, the language that binds roughly 10 million Filipinos culturally and politically. This too speaks of how expertly Enrile has ridden the Philippines’ patronage and region-based politics.

“Because Philippine politics is organised based on personal relations instead of ideology, it’s very easy for Mr Enrile to survive all these years,” says Ms Franco.

He himself shows no signs of giving up.

“Ninety-nine is a long time in terms of years, but a flickering moment in terms of eternity. C’est la vie! That is where we are all going. It is a race no-one wishes to win!” he said on his birthday.

For Filipino millennials and Generation Z, Mr Enrile is the politician who was born before Mickey Mouse and sliced bread – and they swap memes to that effect.

But for those who were kidnapped, tortured and raped by state forces during the Marcos years, Mr Enrile remains the martial law administrator and Marcos Sr’s powerful right-hand man.

Mr Enrile himself has denied all allegations of human rights abuses by the state, saying Marcos Sr’s government “never adopted a policy of killing people with impunity”.

“I do not have any regrets except perhaps if there were people who were hurt because of my judgement, my decisions when I was holding power,” he told the media in 2019 during his losing senatorial campaign.

The fight to make sure young Filipinos never forget what happened under Marcos Sr will likely be a long one – and winning it will take more than protests on the streets, activists say.

Ms Taguiwalo says she and others have been collecting clippings from the “mosquito press” that was critical of Marcos Sr at the time, preserving them in digital format for the younger generation to post and share on Facebook and TikTok.

Ms Franco believes there is still time to take on the Marcoses in their favoured battleground – pop culture and social media.

“If you look at the telenovelas, even the Korean dramas, these are the ones that really stick. The Marcoses know how to use this power,” she says.

“I’ve realised now that People Power is a marathon, not a sprint,” says Ms Taguiwalo who is sitting out the anniversary march on Saturday.

But she is hopeful. When Marcos Jr won last May, she says she received text messages from young voters, apologising for the election result. She said she told them that they must now inherit the fight.

“I don’t move as fast as before, but I know there will be continuity in the struggle.”

Read more of our coverage on the Philippines

Related Topics

-

-

10 May 2022

-

-

-

10 May 2022

-