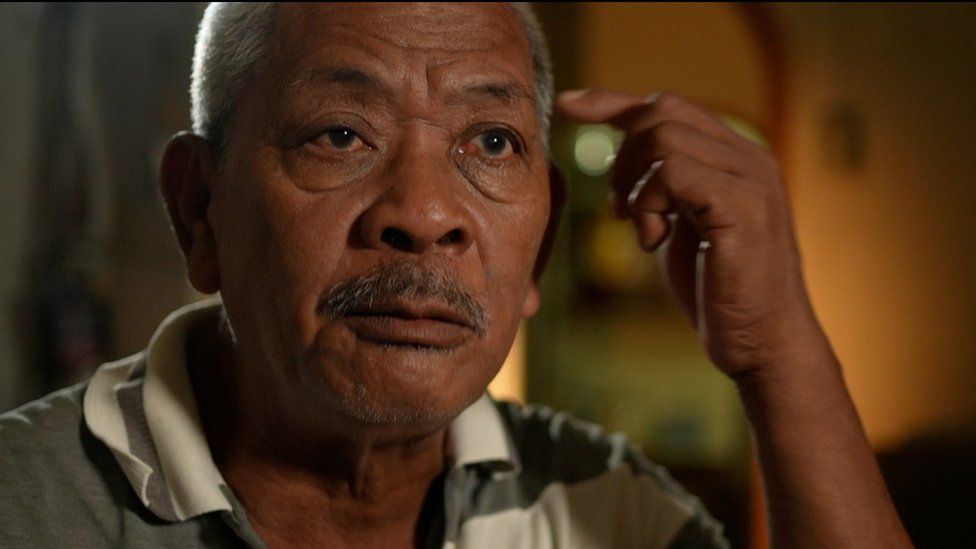

Santiago Matela was 22 when he was dragged off the street by soldiers while playing basketball.

The year was 1977, five years since President Ferdinand E Marcos had declared martial law in the Philippines – on 21 September 1972.

Mr Marcos suspended parliament and arrested opposition leaders – Mr Matela was among the tens of thousands of people detained and tortured during a decade of martial law.

Fifty years on, he is no longer afraid to speak out. But he is afraid of being believed at a time when the truth about one of the darkest periods in Filipino history is under attack.

Mr Matela endured three months of torture, including being tied naked to a block of ice. His captors demanded he admit to being a communist. He says he didn’t even know what that word meant.

“They kept on forcing me to confess that I was leading a rally and throwing grenades. They asked me the same questions again and again and beat me. They used a yantok – a cane – and they hit my body many times,” he said.

“Even my genitals were assaulted by the military just to make you confess what you should not be confessing.”

Some 70,000 people were imprisoned, 34,000 were tortured and over 3,200 people were killed in the nine years after Mr Marcos imposed martial law, according to Amnesty International.

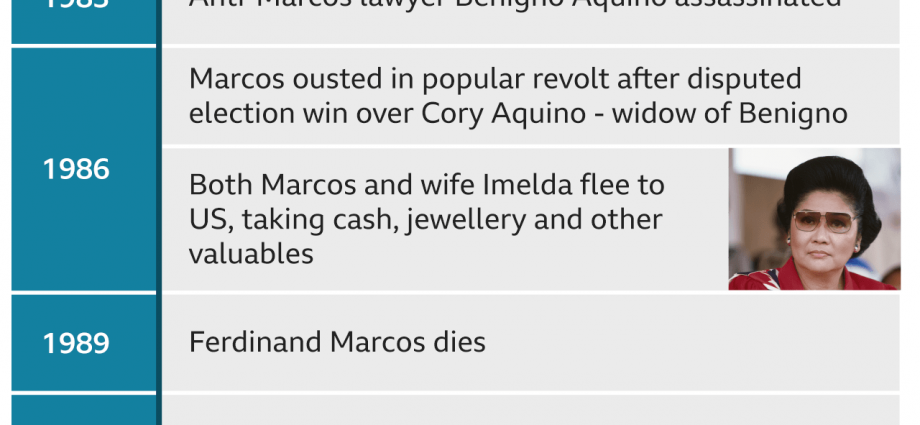

Meanwhile, the Marcos family lived famously opulent lifestyles. Mr Marcos’ wife, Imelda Marcos, amassed a huge collection of art and other luxuries, including hundreds of pairs of shoes.

They deny siphoning off billions of dollars of state wealth while at the helm of what historians consider one of Asia’s most notorious kleptocracies.

Public anger at abuse and corruption eventually led to pro-democracy protests in 1986 and the family were forced to flee to Hawaii where they lived in exile. Ferdinand Marcos died three years later.

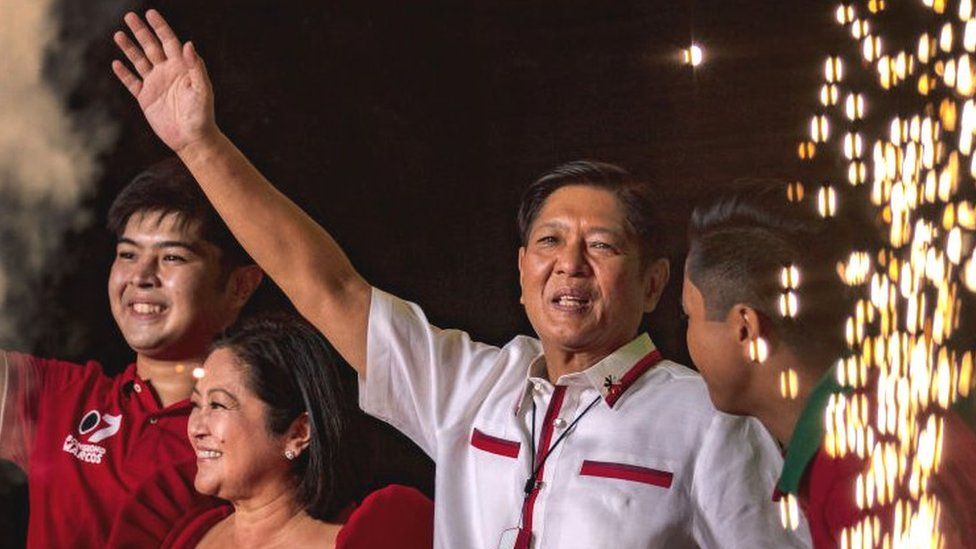

But earlier this year, his son and namesake, Ferdinand Marcos Jr – popularly known as “Bongbong” – led an extraordinary comeback and won the presidency in a landslide victory.

The Marcos rebranding is the result of a major social media operation, aimed at younger Filipinos born after martial law ended. The message seeded in snappy Facebook, YouTube and TikTok posts is that the family has been unfairly treated by the mainstream press.

Mr Marcos Jr has shunned network news interviews and refused to participate in presidential debates. He has made it clear he doesn’t want to discuss the past and has instead focused on a promise to unite the nation and help it recover from the crippling effects of the Covid-19 pandemic.

This popular message, by a recognisable celebrity name, hit home with voters eager for change – including Mr Matela’s children.

Mr Matela tells me that his son believes the past should stay in the past, a view that he finds upsetting.

“My son is adamantly on their side. He doesn’t know that what I’m doing is all for them. These are my experiences and what I’m fighting for is for their sake too, so that they will know what happened.

“You want me to just disregard what I went through? That cannot happen. The sufferings I went through are embedded in my mind,” he said.

“I’m still fighting because of my pain.”

Disinformation and denial

The Marcos administration insists it has not engaged in disinformation.

Gemma, a fact checker from the news website Rappler founded by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Maria Ressa, says the disinformation being propagated is difficult to quantify.

“It’s not one single page, it’s not one single account, it’s not one single group. The point is that it’s coming at you from various points. We’ve mapped tens of thousands of accounts and groups and pages.

“Many look like official history pages and post content that triggers nostalgia but within that content you will find stories peddling an incorrect narrative.”

Among the most widely spread falsehoods are claims that no arrests were made under martial law.

“Many of the posts deny human rights abuses took place and claim that the only people incarcerated were rebels or criminals or troublemakers,” Gemma said.

The Marcos administration has not responded to the BBC’s requests for an interview.

Mr Marcos Jr has posted an interview on YouTube with his goddaughter where he denies that his father was a dictator.

The Marcos family has never apologised, but more than 11,000 victims, including Mr Matela, have received reparations from the government.

Their written accounts are logged in dozens of numbered cardboard boxes piled high in an archive at the Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission, an independent government body.

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

In a new green room at the centre, a young team are creating their own snappy social media posts – with facts about martial law.

“You have to go where the young people are,” says executive director Crisanto Carmelo.

Fears the past is being rewritten have led to a push to preserve and digitise the detailed accounts of martial law abuse in the hope that they can be placed in a museum. One file recalls how a mother was handed back the body of her brutally tortured and murdered son. The account is too gruesome to detail here.

But will Mr Marcos allow such a museum – one built to honour the victims of martial law – while he is president?

“I am optimistic that he will be magnanimous in victory and serious in his intention to unify the country,” Mr Carmelo said.

“This is the year which marks the 50th year of the declaration of martial law which transformed our country and transformed the lives of many ordinary Filipinos. Many of them are now in their senior years, like me, so a museum is not for me, I lived through it.

“A museum is for the younger generation – to say that this happened to our country and if we can come together, they can determine what type of country and system of government and rules of liberty and democracy they want for the future.”

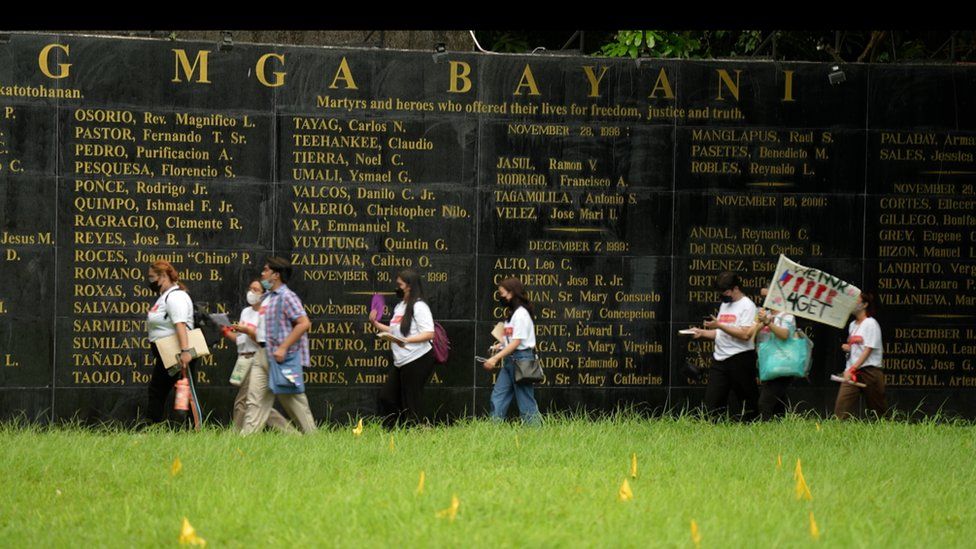

Many young Filipinos are engaged. On a recent popular historical tour, young Filipinos played games to recreate the past.

The idea is to help them pin down the facts and navigate away from a maze of martial law myths.

The teams took selfies together – most of them had met only a few hours earlier. They planted flowers at the memorial with the names of those who died under martial law.

Seventeen-year-old Hannah found the day emotional.

“They’ve lost their dreams, their lives and I wanted to recognise that. I want to go and tell my friends that in order for us to have the liberty and democracy we have today, these were people who sacrificed everything. They suffered a lot of violence and immoral wrongdoings, and they deserve to be recognised.”

It seems that voices from the past, however painful, are helping to keep this country’s collective memory alive.