Nestled in Pakistan’s Hindu Kush mountains, the remote Kalash valley is a popular tourist destination. But a recent attack by Taliban militants has left people living there afraid for their future.

“It was 04:00 in the morning when we saw men coming down the mountain with turbans on their head, backpacks, weapons and belts of bullets around their bodies,” says a Kalashi shepherd, Michael (not his real name).

He was taking sheep and goats to a nearby pasture with his father, uncle and a friend when the militants attacked their valley.

“There were Taliban everywhere, behind every rock and every tree. One was just a few steps away from me. There must have been more than 200 of them,” Michael recalls. “We hid under big rocks and stayed there for 48 hours.”

The Pakistani authorities sent in forces and say five security officers and at least 20 Taliban militants were killed in the fighting that lasted two days.

“There was an unusual stillness. Everyone was worried and scared. It felt like a war zone,” says Shaira, a mother of two, as she recalls hundreds of troops, military vehicles, drones and attack helicopters hovering over the valley.

Attacks like this have become more frequent in Pakistan in recent months, and although this assault in September took residents by surprise, sources within the government have confirmed they received information and intercepted a phone call hinting at an imminent attack at least a week before it happened.

The Pakistani Taliban, or TTP, said they carried out the assault, reportedly from over the border in neighbouring Afghanistan.

Pakistan has consistently accused Afghanistan’s ruling Taliban of providing shelter to TTP members in provinces along its border with Pakistan and this is seen as one of the most significant cross-border attacks since the Taliban retook control in Kabul in 2021. The Taliban government denies the allegations it provides sanctuary to militants.

Authorities in Pakistan believe the aim of the assault was to take control of the strategically-important Kalash valley.

“Its capture would have given the TTP what they want, causing fear among people and a message to the world that they are strong,” says Muhammad Ali, the district’s deputy commissioner. But he points out: “Our security forces didn’t let that happen.”

The attack has left the indigenous Kalashi community, 400km (250 miles) from Pakistan’s capital Islamabad, feeling tense.

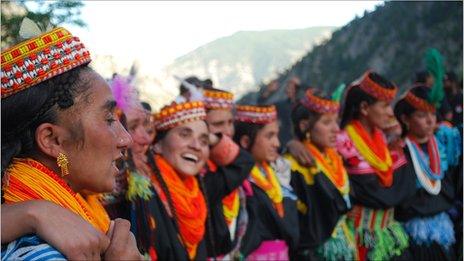

The people in this valley – who claim they are descended from Alexander the Great despite evidence that they are indigenous to South Asia – are renowned for their culture, religion and traditions that are distinct from Pakistan’s Muslim majority.

But the joy they display in their dances and music has been overshadowed by a sense of fear, uncertainty and despair.

As Shaira cradles her one-year-old daughter, she explains that she came back to Kalash after finishing her university degree “to preserve their culture and unique religion”.

The community worships a pantheon of gods and goddesses, holding festivals to mark the seasons and their links with farming. At these times women may declare their love, elope or even end their marriages.

But living in a maze of tiny houses, the people here also face challenges and threats of forced conversions by both Muslim and Christian groups.

And they now fear the latest attack represents a new wave of threats that could spell the end of their community. Many, like Shaira, are wondering what their options are. Where should they go if the Taliban attack again?

“Everyone said the Taliban had come for us Kalashis. They’ll kill us or force us to change our religion,” she says. “We don’t have any resources to leave, so we have to stay in Kalash, dead or alive.”

They are worried that attacks like this could also affect their livelihoods. The Kalash valley attracts a significant number of visitors each year from Pakistan and beyond.

The clash brought both tourism and shepherding in the area to a standstill, as the valley was closed for days. Foreign tourists were evacuated, locals were instructed to stay away, and all roads leading to the valley were barricaded. Troops were deployed, and the pastures became no-go areas.

“Tourists benefit us all, and after this attack, we faced shortages of essentials,” says Kai Meera, a community leader. “We were also unable to take our livestock to the pastures, and there was a complete loss of income.”

After the attack, Pakistan announced the closure of two main border crossings with Afghanistan, which resulted in substantial losses in trade revenue. Thousands of people were stranded at the border crossings for days.

Michael managed to leave his hiding place under the rock after 48 uncomfortable and terrified hours. His body had been bent over for so long he couldn’t walk for a while.

Now back in his village, fear is a constant in his life.

“They [militants] used to cross the border in the past, but they would snatch our livestock at gunpoint and go back. This time they came to take our valley away. I think they’ll come again,” he says.

The deputy commissioner has tried to reassure Michael and the rest of the community, saying: “While it may take some time for the fear to subside, we have decided to fortify the border, increase the number of checkpoints, and bolster border security.”

Shaira shares a parting thought as she leaves her baby sleeping soundly and heads to the fields to gather crops before the winter falls: “War is war, whether it’s the Taliban or someone else. In the end, it’s us, the unarmed people, who suffer and die.”

-

-

21 May 2011

-