In 2018, Byju Raveendran was the toast of India’s start-up world as his eponymous edtech company, Byju’s, was crowned a unicorn.

Through the pandemic, as schools shut, Byju’s kept growing and expanding – until it all started to unravel.

Once India’s leading privately-held company valued at $22bn (£17.38bn), it is now regarded by some as a cautionary tale for domestic start-ups, as investment company BlackRock recently slashed its valuation to $1bn.

On 23 February, a majority of shareholders in Byju’s parent company Think & Learn (T&L) voted to remove Mr Raveendran as CEO during an extraordinary general meeting (EGM), citing allegations of “mismanagement and failures.”

Mr Raveendran and his family deny the allegations, disputing the vote’s validity and claiming it violated internal company laws requiring at least one founder-director present at the EGM. In a letter to employees the next day, Mr Raveendran called the meeting a “farce” and challenged it in court.

The Karnataka High Court has temporarily halted the implementation of the resolutions passed in the EGM as it hears the case.

The events were the latest in a growing mountain of legal and financial crises the edtech firm has been battling in recent years.

In the past year alone, Byju’s has faced mounting debt, unhappy investors, lawsuits by lenders, an investigation by India’s financial crimes agency, layoffs of thousands of employees, delayed salaries and a liquidity crisis.

In January, after several missed deadlines, T&L had reported a consolidated loss of 82.3bn rupees ($1bn, 792.3m) for 2022. The company is yet to present its audited financials for 2023, missing the December deadline it had set last year.

Byju’s has also been accused by customers of pressure selling – allegedly coercing parents into buying courses they couldn’t afford. Social media is flooded with complaints accusing the company of jeopardising the savings of vulnerable people. In 2021, the firm dismissed these allegations as “baseless and motivated.”

This month, Byju’s told its employees their salaries would be delayed as it could not access funds raised during a rights issue. A month ago, the company said it had struggled to pay salaries due to lack of money.

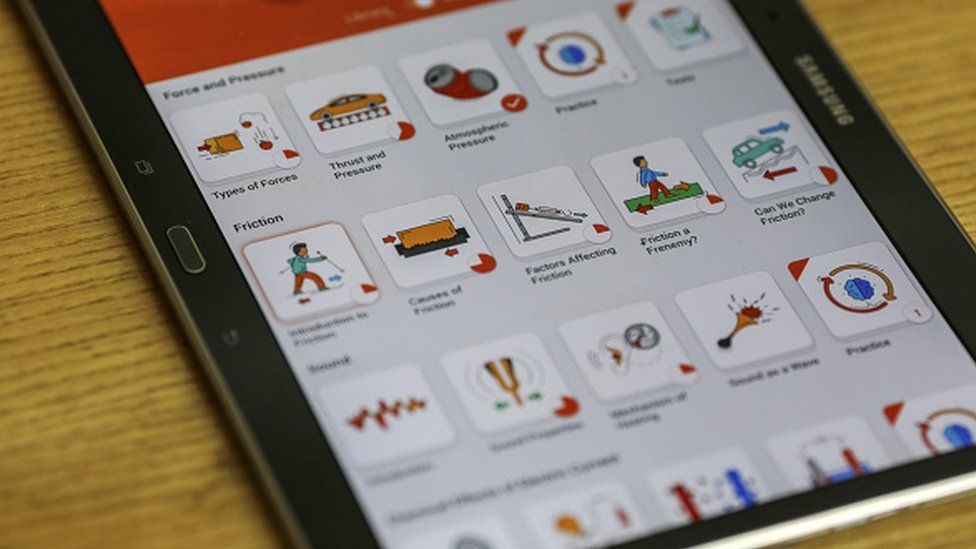

Byju’s, established in 2011 as an online tutoring firm, initially focused on classes for schoolchildren and competitive exam preparation in India. The firm later expanded to introduce learning apps in various Indian languages. A significant portion of Byju’s revenue came from the sale of hardware such as tablets, SD cards, and laptops hosting its educational content.

In 2021, the company spent billions to expand globally, acquiring other edtech start-ups and firms such as Aakash, Toppr, Epic, and Great Learning.

The current standoff between Byju’s and its investors stems from the company’s efforts to address a cash crunch by proposing a rights issue, seeking to raise up to $200m – an invitation to existing shareholders to purchase additional new shares in the company.

Ahead of the EGM, Mr Raveendran said the issue was fully subscribed and the company would appoint a third party agency to monitor how these funds are used.

But the company’s valuation has declined sharply. This means investors who did not participate in the right issue may see their stake in the company significantly diluted.

“No investor likes this,” says K Ganesh, an angel investor who founded one of India’s largest online grocers, BigBasket.

“If you don’t put money, you’re gone. But if you do put, it’s good money over bad money. There is no winner here.”

Four Byju’s investors filed a petition with the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT), a quasi-judicial authority overseeing corporate disputes, seeking to block the rights issue.

The tribunal instructed Byju’s to keep the proceeds from the rights issue in a separate account until the resolution of the investors’ petition. Investors have petitioned the Supreme Court, seeking a hearing in the event of Byju’s challenging the tribunal’s decision.

Meanwhile, in a Florida court, lenders accused the company of siphoning $533m into an obscure hedge fund in the US.

But the firm denied the allegation, saying “an offshore subsidiary remains the beneficiary of the money” which it has invested in “high security fixed income instruments” with a multi-hundred billion dollar fund in the US.

Camshaft, a wealth manager who had managed the funds, told the court that the money was transferred to a 100% subsidiary of Byju’s. In a statement, Byju’s said this was consistent with its position that “group entities remained the beneficiary holders of the money”.

A lead sponsor of the Indian cricket team till 2023, Byju’s is in arbitration with the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) after being sued for allegedly failing to fulfil its sponsorship obligations and not paying dues of 1.58bn rupees.

On 22 February, India’s financial crimes agency, the Enforcement Directorate, issued a look-out notice against Mr Raveendran in connection with alleged foreign exchange violations involving 93bn rupees.

In a statement to the BBC, Byju’s said the ED had concluded its investigation. “Byju’s maintains and will continue to maintain complete adherence to all relevant FEMA (Foreign Exchange Management Act) regulations,” the firm said.

Local reports say Mr Raveendran is currently in Dubai and has been shuttling between Delhi and Dubai for the last three years. Byju’s did not comment on Mr Raveendran’s whereabouts.

The company’s biggest challenge would be to shore up funds, says Shriram Subramanian, who heads an independent corporate governance research and advisory firm.

Last year, three of its board members – V Ravishankar of Sequoia Capital (now Peak XV Partners), Vivian Wu of Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, and Russell Dreisenstock of Prosus – resigned, leaving just Mr Raveendran, his wife Divya Gokulnath and brother Riju Raveendran on the board.

Mr Subramanian says sometimes it’s a good thing for companies to “fail and fail fast”.

Instead of chasing valuation, companies should put in place robust business practices and “play the long game”, he says. “Raising money and going for valuation every few days is all humbug.”

Others, however, feel that the company’s problems should not be seen only through the lens of profit and loss.

Public discussion on the Byju’s “continues to be in the languages of good and bad corporate management,” Sanjay Srivastava, a professor at SOAS University’s department of anthropology and sociology, wrote in the Indian Express newspaper.

Srivastava describes this as a “fast-food model of education” which has “been converted to a machine for profit-making without much proof that it produces any public good”.

Irrespective of the outcome, the crisis is unlikely to affect Mr Raveendran himself, experts say.

Mr Ganesh says that while a comeback for the CEO would be “a daunting task”, Mr Raveendran is still “a terrific entrepreneur” who built a large business and raised huge amounts of money.

Besides, a “reasonable, stable outcome” for the company is also important for India’s start-up ecosystem, he adds.

“This is India’s largest start-up and the world is watching.”

Read more India stories from the BBC: