For their significant contributions to how organizations influence economic growth, Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson were each awarded the 2024 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics. Some may argue that it was long overdue to honor these scientists the Nobel.

One of the most frequently mentioned in finance is the document that served as the foundation for their work. Acemoglu and Robinson’s following book, Why Governments Fail, has also been enormously important.

Congratulations are in order in that regard because these works have sparked a lively discussion about the relationship between cultural institutions and economic development. They have even drawn a lot of censure, though. It is appropriate to identify the flaws in their analysis in the wake of the award.

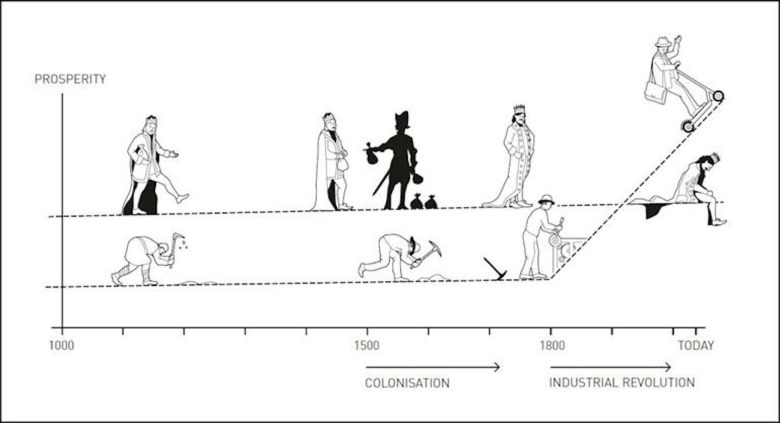

The most significant criticism centers on the relationship between a nation’s level of social development and the quality of its political institutions. Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson’s job split organisations into two groups: “inclusive” and “extractive”.

Equitable institutions – such as those that enforce property privileges, protect politics and control corruption – foster economic growth, according to the laureates. In contrast, industrial institutions, which give rise to a higher concentration of power and limited social freedom, get to focus resources in the hands of a tiny elite and therefore stifle socioeconomic development.

The winners assert that the establishment of diverse establishments has had a beneficial long-term impact on economic growth. In fact, these organizations are present mainly in high-income nations in the west.

A big problem with this study, however, is the state that certain organizations are a requirement for economic growth.

Mushtaq Khan, a professor of economics at Soas, University of London, has analysed Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson’s work thoroughly. He contends that it primarily demonstrates that today’s high-income nations perform better on institutional standards from the West, rather than that economic growth was achieved as a result of the establishment of inclusive institutions by state.

In fact, there are numerous instances of nations growing quickly without having these diverse organizations in place as a prerequisite for development. South Asian states such as Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan are good examples. Most lately, so too is China.

The problem epidemic in China during the development process was detailed in Yuen Yuen Ang’s award-winning books on the subject. In response to this year’s Nobel Prize, Ang went so far as to claim that the laureates ‘ theory does not adequately account for growth in both China and the West. She makes the case that during the creation process in the US, establishments were smeared with corruption.

Ignoring the cruelty of colonization

Governments are not bad to do some of the diverse organizations outlined in Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson’s job. Another alarming aspect of their research is that it legitimizes American institutions and, at worst, colonialism and colonization.

Their job has, however, been criticized for not paying attention to the cruelty of imperialism. To know this criticism, we must dig a little deeper into their procedures.

The laureates establish their state by comparing settler colonies to non-settler colonies for long-term development. In resident provinces, such as the US, Canada and Australia, Europeans established diverse institutions. But in non-settler provinces, which include large pieces of Africa and Latin America, Europeans established industrial organizations.

Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson place out that, over time, settler provinces do better. Western institutions are therefore better for growth, they argue.

However, it’s a secret that the laureates do not explain colonization in more general terms given that the process of colonization is a key component of their papers.

Years of murder, in many cases evoking the genocide of local populations, predated the development of such institutions yet in settler colonies, where equitable institutions were gradually established. Should n’t this be taken into account when developing?

Instead of arguing whether imperialism is good or bad, Acemoglu said,” We note that different colonial methods have resulted in different institutional trends that have persisted over moment,” the awardee added.

Why does Acemoglu not care whether imperialism is good or bad, as some might discover from this statement? But for those familiar with the inner workings of the economics discipline, this statement does n’t come as a surprise.

Unfortunately, the absence of a ethical glass or value judgments has unfortunately become a badge of honor in mainstream economics. This is a more important aspect of the discipline, which in turn explains why economy has become more remote and isolated from different social sciences.

The Nobel prize in economics, which really was n’t among the five original Nobel awards, also illustrates this problem. The list of previous winners is small in terms of both geographical and organisational scope, primarily made up of economists who are graduates of economics faculties at a select few elite US universities.

Additionally, a recent study found that economics awards are much more concentrated in the administrative and regional areas than in other academic areas. Nearly all of the major award winners have had to travel through one of the major US institutions ( with a cap of less than ten ) throughout their careers.

This month’s Nobel Prize in economics is no exception. Perhaps this is why it seems like each year the winner is chosen over those who ask “how does a change in changing X affect variable Y” rather than posing complex questions about colonialism, imperialism, or capitalism and waging a challenge on the legitimacy of European institutions.

Jostein Hauge is associate professor in development research, University of Cambridge

The Conversation has republished this post under a Creative Commons license. Read the original content.