On this day 10 years ago, a young woman was gang-raped and brutally assaulted on a bus in the Indian capital, Delhi. She died a few days later from her injuries.

As she lay in a hospital bed, fighting for her life, the press named her Nirbhaya – the fearless one. Since rape victims can’t be named under Indian law, the name stuck.

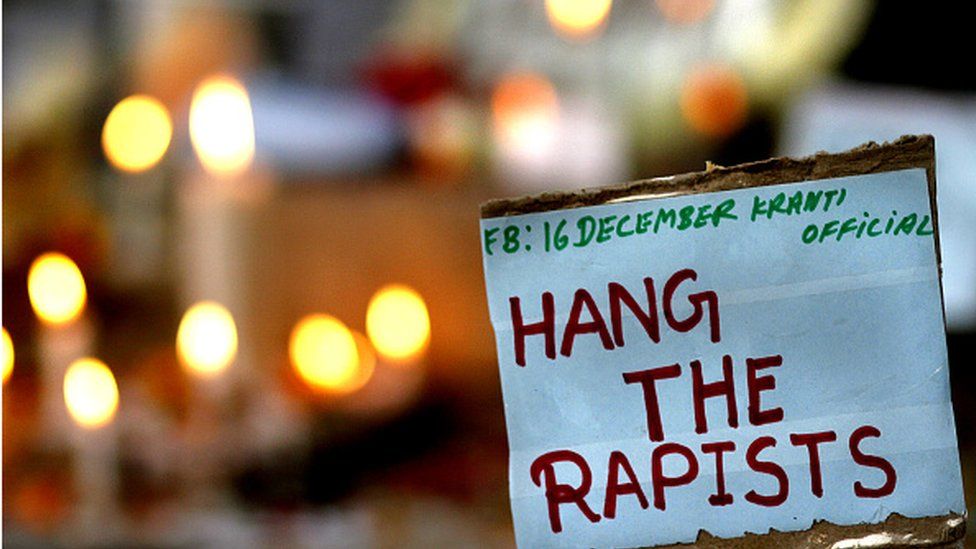

The assault made global headlines, led to weeks of protests and forced India to introduce stringent new laws for crimes against women.

The main accused, the bus driver, was found dead inside the jail a few months after the crime. Four others were hanged in March 2020 while a juvenile convict was released after three years – the maximum punishment allowed under law.

The crime changed the way Indians discussed gender violence and altered many lives – none more than that of Asha Devi, Nirbhaya’s mother.

A quiet housewife who’d spent her years looking after her home and children has, over the past decade, transformed into an activist and a campaigner for women’s safety, fighting for justice first for her own daughter and now for “all of India’s daughters”.

Two years ago – on the 8th anniversary of the attack on her daughter and a few months after the hangings – she pledged to “fight for justice for all rape victims”.

“This way, I’ll be able to pay tribute to my daughter,” she said.

Despite a crippling leg pain that requires daily visits to a physiotherapist, the 56-year-old has been leading a small group of people on a candle-light march in Delhi’s Dwarka district every evening for the past five weeks.

They are demanding justice for a 19-year-old woman who was gang raped and murdered 10 years ago. Three men who were given the death penalty for the crime were recently let off by India’s top court which said there was no clinching evidence that the men were guilty.

A review petition has been filed in the top court, but Asha Devi and others have been holding protests to ensure the “Chhawla rape case is not forgotten”.

“Some days 10 people turn out, some days there are 15, but we march every single day,” Asha Devi told me when I visited her home recently.

“We want the court order to be reversed. They [the alleged rapists] must go back to jail.”

The day after the Supreme Court order, Asha Devi went to meet the victim’s parents.

“I got justice and I don’t have to go out and do anything anymore, but I remember how I used to sit outside the courtroom and cry, sometimes alone. I think that should never happen to anyone else. So I went and sat with her parents and wept with them,” she says.

She recently also lent her support to an online petition calling for justice for Bilkis Bano after 11 men convicted for raping her and murdering several of her family members were prematurely freed by the Gujarat government.

A trust Asha Devi set up in her daughter’s name to help rape survivors and advise victims of domestic violence has retired judges, lawyers, police officials and activists as volunteers. Over the past few years, they have worked with dozens of families.

Her presence often spurs police and authorities into action, but Asha Devi says that 10 years after her daughter died, nothing has changed on the ground.

In 2012, the year Nirbhaya was attacked, India recorded 24,923 rape cases. In 2021, the last year for which crime data is available, the number had risen to 31,677.

“Laws are made on paper, promises are made, but there’s poor implementation,” says Asha Devi. “If this continues, it will take away our faith in justice.”

Asha Devi’s activism is rooted in her own experiences, her own lengthy battle with justice and the pain of a mother who lost her daughter to brutality.

Ten years on, the memories of that Sunday still bring tears to her eyes.

“No one should have to see a day like 16 December,” she says.

Her 23-year-old daughter had just completed her training as a physiotherapist; she had been interviewed at a couple of hospitals and was accepted at one for an internship.

“She had already received an ID card from the hospital and was to start on Monday or Tuesday. She told me, ‘Ma, your daughter is a doctor now.’ She was thrilled.”

On Sunday afternoon, when she left home, she’d promised her mother she’d be back in two-three hours.

When Asha Devi saw her several hours later, she was in hospital, bloodied and mauled. Describing her daughter’s injuries, she had told a TV channel “it seemed as if she had been rescued from a jungle. The doctor said he was unable to understand what to do, what to fix and what to mend”.

The young woman was gang-raped by the bus driver and five other men; her male friend was badly beaten up. Naked and bloodied, the couple were thrown by the roadside to die. They were taken to hospital after some passers-by found them and called the police.

“What happened to her was so brutal that she shouldn’t have survived,” says Asha Devi, “but she lived for 12 days. They named her Nirbhaya, she truly was brave.”

The “biggest regret” of her life”, she says, wiping her tears, is that while her daughter was alive, “she kept begging for water, but we couldn’t give her a spoon of water”.

“I kept thinking, what was my daughter’s fault? Why did she have to die so painfully? I saw her hurting and I drew strength from her pain. I promised her I’ll fight for justice for her. I only wanted the men who did this to her to be punished.”

As the trial started, Asha Devi became an unmissable presence in the courtroom.

“I did not miss one single court hearing, ignored home, but if there was a hearing, I had to attend,” she says.

Despite the attention on the crime, it took more than seven years for the case to conclude and the rapists to be hanged.

Asha Devi says it took her all her resolve to not give up.

She grew up in a backward district in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh and “had to drop out of school after the eighth standard because the high school was too far from home”, and had to work hard to understand the language of law and learn how to give press conferences.

But the raw agony of the grieving mother, often captured by TV cameras, moved many Indians and drew lawyers, activists, celebrities and politicians of all hues to lend support to her. Protests were held across India demanding the death penalty for the rapists.

But once the death sentences were confirmed by the Supreme Court in September 2017, the convicts’ families and their lawyers began last-minute attempts to stay the hangings by filing review petitions and writing to the authorities for clemency.

Campaigners also pointed out that studies globally had shown that death penalty doesn’t reduce crimes – it actually results in more killings as perpetrators try to remove evidence.

But Asha Devi, a huge votary of capital punishment, insists that it was justified.

“There are people who talk about the human rights of the accused, but what about the human rights of the girl who is raped and brutally murdered? Until people feel fear nothing is going to change,” she told me.

As the case meandered through the Indian judicial system, Asha Devi says sometimes people told her “your daughter has left the world, give up, you’re banging your head against a stone”.

“But I got tremendous support from society. And that made me think that they don’t know my daughter but if they are standing by her, so must I.”

Asha Devi says she “did feel afraid sometimes”, but kept her faith.

“I used to think that if these men were not hanged, then who would? What would make a rarest of the rare case for the death penalty?

The case went through several twists and turns before the convicts were hanged at 5:30am on 20 March 2020.

“I couldn’t save her, but when they were hanged, I felt peace, because they paid for what they did to my daughter,” she told me.

Shruti Singh, a gender rights activist who was working with Asha Devi for almost a year then, described the night of the hanging.

“We didn’t wait outside the prison where the hangings were taking place. We went home to be with Nirbhaya.”

They sat in the room where her photo hangs on the wall.

“Now we are able to show you our face, we didn’t let you down,” Asha Devi told her daughter.

Read more India stories from the BBC:

- Is India seeing a surge in grisly copycat murders?

- Shadow of 60-year-old war at India-China flashpoint

- Why is consensual teen sex a crime in India?

- Why Modi continues to be India’s biggest vote-getter

- The Indian women calling themselves ‘proudly single’

- The good people helping laid-off Indians in US