North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, perhaps emboldened by his embrace of Russia’s war in Ukraine, has unleashed a wave of missile tests with a possible nuclear test to come. The Pyongyang regime claims to be developing tactical nuclear weapons and to be responding to recent joint military exercises by the US, South Korea and Japan.

Ironically, the most immediate impact of North Korea’s relentless pace of missile testing, highlighted by the flight of an intermediate-range missile over Japan on October 4, has been to draw Japan and South Korea closer and to give life to entreaties by the US to its two allies to join in closer trilateral security cooperation. The most significant sign of this shift was visible two days later in the waters between Korea and Japan.

In those seas, two American guided-missile ships were joined by two Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force destroyers and the Korean navy’s most advanced destroyer in carrying out a first-ever trilateral ballistic missile defense exercise. During the same week, the three countries carried out joint air exercises as well.

This was a highly symbolic move toward, as the US Indo-Pacific Command put it, “the interoperability of our collective forces.” The exercise involved the detection, tracking and interception of potential incoming missiles, with almost instantaneous sharing of information among the three navies.

This kind of quiet cooperation on missile defense has been going on for several years, with Korea providing tracking data on North Korean launches to the de facto joint US-Japan Air Defense Command set up at Yokota airbase outside Tokyo.

“North Korea’s unprecedented series of ballistic missile tests, its newly legislated nuclear doctrine and threats to carry out preemptive nuclear attacks and the prospect of a seventh nuclear test (and more to come) have served as a powerful reminder to Tokyo and Seoul of the common danger they face,” observes former senior US State Department official Evans Revere.

“That danger has encouraged the ROK [Republic of Korea] and Japan to work together, and with the United States, to confront their shared threat by strengthening defenses, increasing readiness, and enhancing bilateral and trilateral security cooperation.”

The creation of a more formal trilateral missile defense structure is the logical next step, though it faces considerable political hurdles in both Korea and Japan. This possibility has alarmed not only the North Koreans but also the progressive opposition in South Korea.

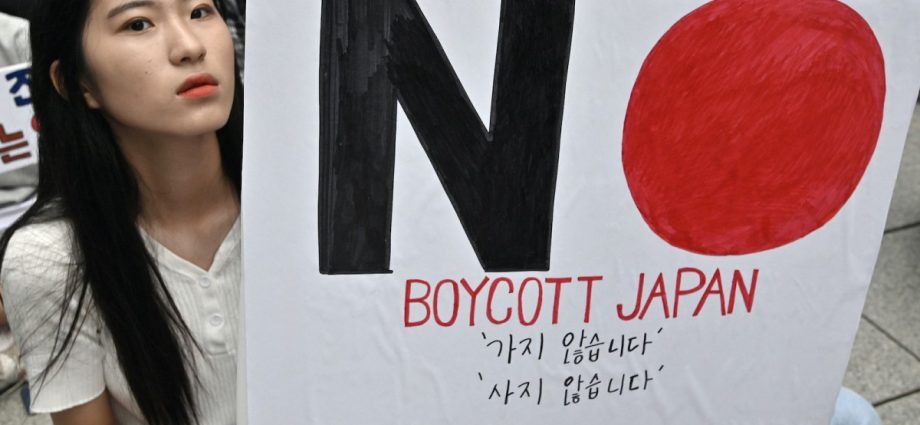

The leader of Korea’s Democratic Party, Lee Jae-myung, made headlines by denouncing the trilateral drill as a “pro-Japanese act” that was heading toward the creation of a military alliance.

“We cannot imagine the day when the Japanese military invades the Korean Peninsula and the Rising Sun Flag again hangs over the peninsula, but it could come true,” railed Lee, who narrowly lost the presidential election earlier this year to conservative Yoon Suk-yeol.

The ruling People Power Party (PPP) quickly denounced Lee’s inflammatory remarks as “a frivolous take on history.” But President Yoon is struggling with sagging popularity ratings that make him vulnerable to the Democratic Party, which continues to control the National Assembly and is sharply critical of the President.

“The Korean public is generally supportive of improved relations with the US, cautious regarding China, generally supportive about Japan,” says Scott Snyder, who heads the Korea program at the Council on Foreign Relations. “Overall Yoon is doing what South Koreans want to see in foreign policy – but increasingly he is in danger of not getting credit for it and is in danger because of his own unpopularity.”

Despite those problems, Yoon’s efforts to make a breakthrough with Tokyo have broad backing in Korea. In their recently published annual poll of Japanese and South Korean opinion, Japan’s Genron NPO and the Korean East Asian Institute found a significant shift in positive views toward each other.

It was the largest improvement since the survey began a decade ago, with the most marked change in South Korea. In particular, the Genron-EAI poll showed a growing fear of China in Korea, beginning to echo what has been the case in Japan

Solving the forced labor problem

Trilateral security cooperation, even with the North Korean threat to propel it, still depends on solving the wartime historical issues that arose out of Japan’s colonial rule over Korea. Japanese and Korean officials, and their American counterparts, emphasize the need to look forward – but all also understand that the history problems are a sword of Damocles, always threatening to send Korea-Japan relations back into a deep freeze.

Attempts to resolve the issue of compensation for the Koreans forced to work in Japanese mines and factories during the wartime period remain stalled, with a looming threat by Korean courts to seize the assets of Japanese companies that used that labor.

Publicly, Japanese officials continue to insist that they are waiting for Korea to make a concrete proposal to resolve the forced labor problem. According to multiple Korean official and other sources engaged in this issue, however, a proposal is on the table and is being actively discussed at the director-general level of the two foreign ministries, most recently on Tuesday in Seoul.

Japanese Foreign Minister Hayashi Yoshimasa and Korean Foreign Minister Park Jin, who have a longstanding and friendly personal relationship, have held detailed talks, most recently in New York at the United Nations.

The Korean proposal emerged out of the advisory group that was formed in the summer under the leadership of Korean Vice Foreign Minister Cho Hyun-dong. The Korean idea is to compensate up to 300 South Korean victims with payments made through an existing fund – the Foundation for Victims of Forced Mobilization by Imperial Japan – set up by the Korean government in 2014.

The fund already has a significant contribution from the Korean steelmaker POSCO, which benefited from Japanese economic assistance provided under the 1965 Japan-Korea Claims Agreement that accompanied the normalization of relations between the two countries.

Using this fund indirectly acknowledges Japan’s insistence that compensation was settled by that 1965 agreement. The amount of money already in the fund is more than sufficient. But the victims who filed suit in Korean courts, and their legal representatives who participated in the advisory committee meetings, insist that the Japanese companies also contribute to this fund.

Park proposed two steps to be taken by Japan, according to a senior Korean official who has been working on this issue for many years. “One is that the Japanese government and the related companies have to express regrets,” he told this writer. “The other is that the Japanese government should allow the private sector to contribute voluntarily to the compensation fund.”

At this moment, the Japanese officials involved in the talks have not ruled out this solution. “The Japanese side does not show a negative attitude toward the voluntary contribution of Japanese firms,” says Ambassador Wi Sung-lac, a former senior foreign ministry official and a foreign policy advisor to Democratic party leader Lee. To that degree, “bilateral consultation is moving forward,” says Wi, who is actively involved in these efforts.

Korean officials are concerned about the lack of apparent readiness on the part of Prime Minister Kishida and his advisors to grasp this moment. For the Korean government to be able to sell this proposal within Korea, where it will undoubtedly face fierce attack by the progressives, it is essential that Japan take a step forward.

“Money itself is not a problem,” says the senior Korean official. “Rather it is a matter of pride and emotion. But the Japanese government seems to be very reluctant to agree on a deal to resolve the issue.” The Japanese have yet to budge from their standing position that this issue was settled by the 1965 agreement and are reluctant to reopen it in any way.

The largest obstacle to this agreement remains the domestic politics of both countries. “The political weakness of Yoon and Kishida is a factor that influences the process,” says Professor Park Cheol-hee, one of the most influential Korean scholars on Japan and a close advisor to the Yoon government.

The opposition Democrats in Korea are poised to oppose this bargain. Wi has proposed the creation of a bipartisan group that might include Democratic party leaders who back the deal and has been publicly urging Yoon to take this approach.

But it is equally crucial for Prime Minister Kishida to be prepared to offer the kind of gestures that might make it possible to garner broad public support in Korea. Japan needs to go beyond its overly legalistic stance, argues US Korea expert Snyder. “The Koreans need some kind of reciprocating gesture from the Japanese side in order to make it sustainable.”

Unfortunately, Kishida remains imprisoned by the right wing of the Liberal Democratic Party, which deeply distrusts the Koreans. And that is compounded by his own political weakness, which increasingly mirrors that of Yoon.

Domestic politics, not the absence of a viable compromise proposal, is the real obstacle on this narrow pathway to restoring normal ties between Japan and Korea.

“Going forward, Yoon and Kishida are likely to move slowly to avoid getting out too far ahead of the respective publics,” says Revere, who has long experience as an American diplomat in both countries. But the window of opportunity may not be open long – the Japanese and Korean officials now holding talks are looking to make a deal by the end of the year.

In that timeframe, Revere says, “North Korea can be counted on to remind Seoul and Tokyo that they have a strong common interest in working together.”

Daniel Sneider is a lecturer on international policy at Stanford University and a former Christian Science Monitor foreign correspondent.

This article originally appeared in The Oriental Economist and is republished with kind permission. Follow Daniel Sneider on Twitter at @DCSneider