“The earth shook,” says cattle farmer Win Zaw, recalling the sunny morning last week when he heard a military aircraft approaching, and then an explosion.

He didn’t think it was his village – Pa Zi Gyi in north-east Myanmar – that had been hit. But when he phoned his wife, he learnt that the military had bombed the place where villagers had gathered for a rare feast of curried noodles, rice and pork. Their seven-year-old daughter, Soe Nandar Nwe, had been among them.

He says he rushed to the site of the attack and tried looking for her among the carnage. “I searched for my daughter in the smoke, and through the charred remains. All I could think of was finding her.”

He was looking for any sign of her favourite outfit – a white, floral dress that she wore that day. But he says he found no trace of her, or his mother-in-law who had been with her when the bomb fell.

Villagers later told the BBC that a military jet dropped a bomb where people had gathered for the meal, and then a helicopter gunship fired at the village for 20 minutes.

“I still can’t believe it,” Win Zaw says. “How could they have done this to defenceless, vulnerable little children?”

Two years after a coup plunged Myanmar into a civil war, the country’s military rulers have increasingly taken to the skies to reduce resistance literally to ashes. Last Tuesday’s attack, which killed 168 men, women and children, is among the deadliest so far. Last year, the military struck a school, killing several children, and later that month, a bombing of a concert killed about 50 people.

Between February 2021 and January 2023, there had been at least 600 air attacks by the military, according to a BBC analysis of data from the conflict-monitoring group Acled (Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project). The civil war has claimed thousands of lives, displaced some 1.4 million people and left nearly a third of the country’s population in need of humanitarian aid. The United Nations has said the regime could be liable for crimes against humanity and war crimes.

The attacks target villages that are thought to be aligned with the resistance, which now comprises ethnic armed groups; a loose network of local volunteer militias known as People’s Defence Force or PDFs; and the exiled National Unity Government, which was formed after the coup.

In Pa Zi Gyi, the regime said it specifically targeted the village because it had opened an administrative office for the local PDF, which is affiliated to the NUG.

The office and the feast to celebrate its opening were an unacceptable sign of the community’s resistance.

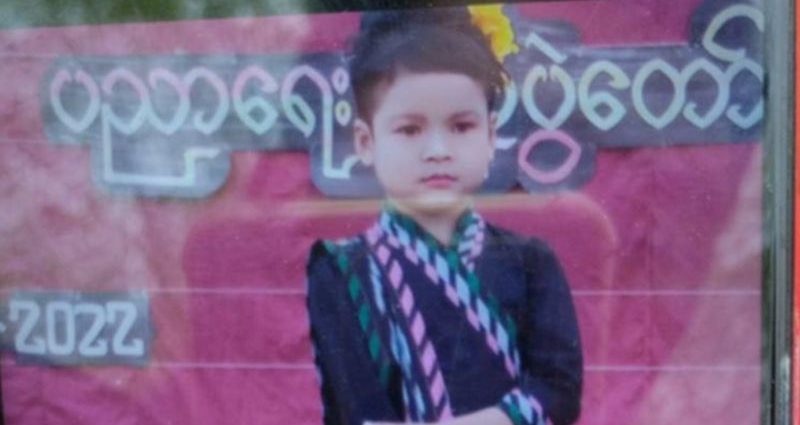

For Soe Nandar Nwe, it was simply an opportunity to show off her favourite floral dress. The night before she had told her father how excited she was for the neighbourhood event.

“I’ve never called my daughter by her name, always daddy’s sweetheart. And she loved me.” One of their favourite things to do together, he says, was to take bike rides together, with her on the back seat, hugging him.

That night, Soe Nandar Nwe insisted on sleeping by her father’s side. His last memory of her was when he kissed her before leaving for work the next morning. She was still sleeping.

Win Zaw says his daughter was a smart girl who wanted to be a teacher.

”She loved helping her friends study. We wanted her to grow up and achieve big things for the country because our country is going through a very difficult time.”

Win Zaw imagined coming home that morning to loud music because the village had not celebrated even a wedding since the coup in 2021 that ousted Myanmar’s elected leader Aung San Suu Kyi.

He was supposed to take his daughter to the feast, but she had been so excited to go that her mother dropped her off at the venue earlier than planned, with her grandmother.

They were inside a pandal or makeshift tent at the centre of the festivities when the attack began.

It was the first air strike on Pa Zi Gyi although the region, Sagaing, which is home to some of the fiercest resistance to military rule, has been subject to several such attacks.

Farmer Ye Naing also lost both his parents and his three-year-old daughter Hnin Yu Wai in the air strike.

That morning before the attack, Ye Naing helped his daughter apply thanakha or face paint made from tree bark, traditionally worn to celebrations.

She was among many children who had gathered for the feast before heading to school because meals like that have become a luxury in a country devastated by violence.

The bomb fell just as the children were eating, said Ye Naing, who sustained injuries from shrapnel.

“My daughter must not even have finished a small bowl of rice,” he said. “My baby must not have had a cup of water.”

“That day, it felt like the end of the world or worse than that. But I’m not afraid. This was inhumane and barbaric. As long as they are oppressing and killing innocent people. I will fight back, along with the people of the country,” he said.

Ye Naing said his daughter was the darling of the village because she was friendly and thoughtful. When she saw him tired after a day’s work, she would ask her mother to give him water and a snack.

Nearly every one of the 200-odd households in Pa Zi Gyi lost a loved one that day. Villagers say some survivors left their homes and went into hiding, fearing more attacks. Others are rattled by loud sounds, such as motorcycle engines.

“We are just poor farmers. Don’t watch us being killed. How many more innocent lives need to be sacrificed before you take action?” Win Zaw said.

Addressing General Min Aung Hlaing, the leader of the military government, he said: ”I will never forgive him.”

Moe Myint is a journalist for the BBC Burmese Service based in London.

Read more of our coverage on the civil war in Myanmar

- ‘We wish we could go back’: Life in a war-torn Myanmar

- Fighting forces 10,000 Burmese to flee to Thailand

- Devastation from the air in Myanmar’s brutal civil war

- The deadly battles that tipped Myanmar into civil war

- ‘If I get the first shot, I will kill you son’

- Myanmar’s former soldiers admit to atrocities