The recent order of a trial court in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, setting free 41 Hindu men accused of religious violence against Muslims 36 years ago, has plunged the survivors and families of victims into despair.

The violence on 23 May 1987 in Malyana village on the outskirts of Meerut town, in which 72 Muslims were massacred, allegedly by local Hindus and members of the state’s armed police force, has been described as a “blot on Indian democracy”. And critics say Friday’s sessions court order is “a travesty of justice”.

Vibhuti Narain Rai, a former director general of the Uttar Pradesh police, described it as a “total failure on the part of the state”.

“The victims have been miserably failed by all the stakeholders – the police, the political leadership, a partisan press, and now the judiciary,” he told the BBC.

Mr Rai, along with senior journalist Qurban Ali who’d extensively covered the riots, and a couple of survivors of the massacre, had petitioned the Allahabad high court in 2021 complaining about the slow pace of the proceedings.

“The investigation had been faulty from the start and the trial was pending for three-and-a-half decades so we petitioned the high court to order a fresh investigation, hold a fair trial and pay compensation to the victims,” Mr Rai said.

Mr Ali said one of their demands was to revisit the role of the police in the carnage. Survivors allege that the violence was started by members of the state’s Provincial Armed Constabulary (PAC) – a police force created to deal with insurgencies and religious and caste conflicts.

Civil liberties organisations, including Amnesty International, have documented the PAC’s involvement in the Malyana riots. Mr Ali also points out that “post-mortem reports submitted in court of at least 36 bodies show bullet wounds” – at a time when villagers had no access to guns.

The BBC reached out to the PAC for their response to allegations of involvement in the Malyana violence. A senior official said he was “not competent enough to talk about the case”. An email has also been sent to the head of the force.

In the complaint registered by police after the killings, only 93 local Hindus were named as accused – 23 died during the trial and 31 “could not be traced”.

Defence lawyer Chhotey Lal Bansal told the BBC that the prosecution case fell through because the main witness said he had “named the accused under police pressure” and that “police had included names of four people who had died seven-eight years before the carnage and one man who was gravely ill and in hospital”.

“What happened to Malyana’s Muslims was very painful and was highly condemnable. But my clients were also victims, living under threat of prosecution for 36 years,” he said.

“Both the defence and the prosecution repeatedly blamed the police and the PAC for the killings, but their names were not included,” he added.

The 26-page judgement has distressing details of violence narrated in court – a young man killed when a bullet pierced his neck, a father cut into pieces with swords, a five-year-old thrown into a fire.

So the judgement has shocked the survivors of the violence and members of victim’s families.

Vakeel Ahmed Siddiqui, who carries scars from two bullet wounds, says “gloom has descended on the community in Malyana”.

“I know all those who died and all those who killed,” he tells me, adding that he weeps every time he talks about 23 May 1987.

For some days, he says, anti-Muslim rumours had been swirling around in their village and attempts were being made to create animosity between the two communities.

“Meerut had been a powder keg for years and had seen riots, but we didn’t think there would be any violence in our village. But on that day, PAC personnel arrived in three vehicles and surrounded Muslim areas, shutting down all exit routes,” he says.

“Some entered Hindu homes and others took position on rooftops of Hindu homes. Bullets were raining from all sides,” he says.

Mr Siddiqui was among a handful of witnesses who was called to testify in court.

“I gave evidence over a year, I told them about the PAC’s role, identified the men and the weapons they were carrying.”

The judgement, he says, has “disappointed everyone” in Malyana.

“I think there was enough evidence to pin the guilt. We must find out where we went wrong. When Malyana was set on fire, the smoke was seen by the entire world. How could the court not see it?” he asks.

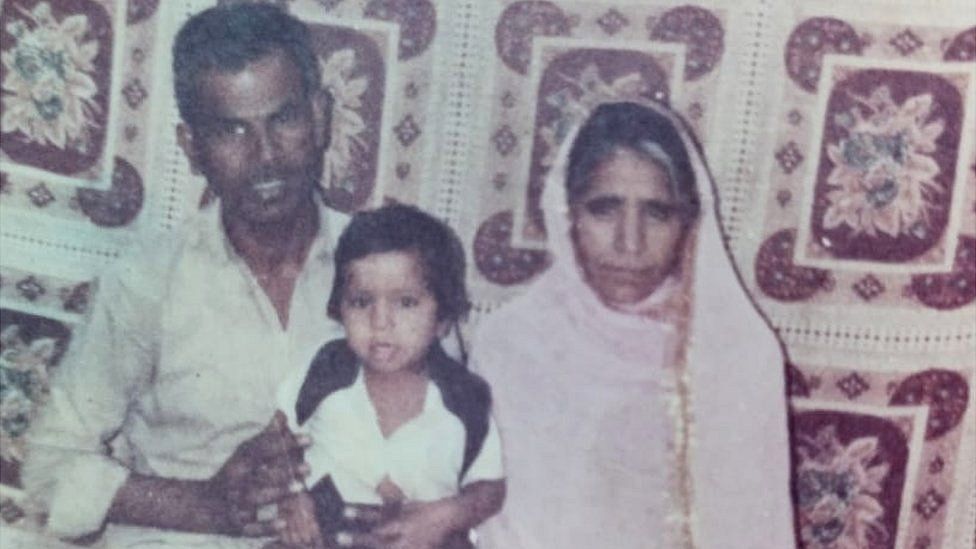

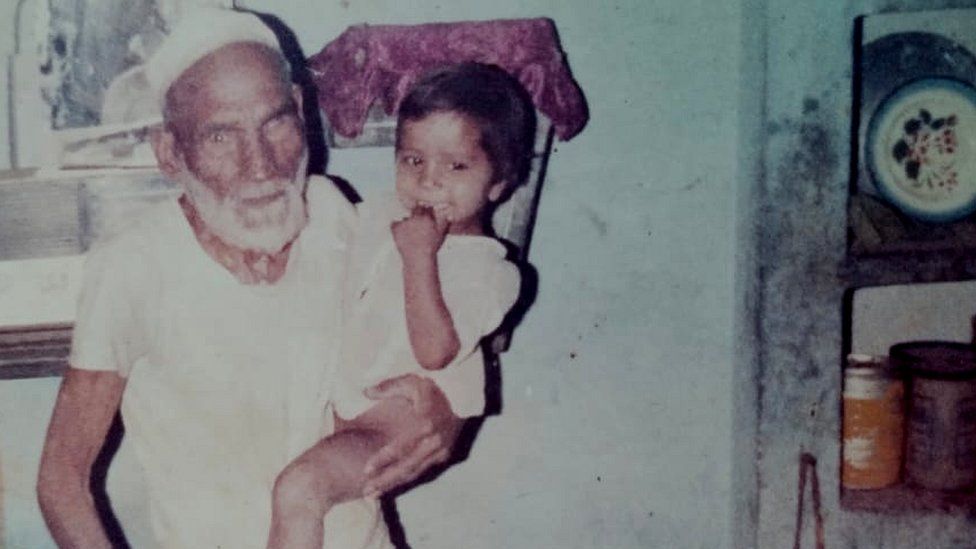

Mohammad Ismail lost 11 members of his family in the massacre, including his grandfather, parents, seven younger siblings and a cousin. The oldest victim, his grandfather, was around 85; the youngest was his sister, a toddler. He survived because he was travelling.

News of the killings reached Mohd Ismail the day after, but he could visit his village only “four-five days later because Meerut was sealed and a curfew was imposed”. What he saw on his return, he says, still haunts him.

“Our house was burnt, the walls were splattered with blood. Some of my Muslim neighbours who had survived had been moved to a nearby madrassa [a religious school.”

Mohd Ismail says even though riots were being reported from other parts of Meerut, his family didn’t think that they would be targeted. “We had no animosity with anyone, so we were not worried.”

Mr Ali, the journalist, told me that when he visited the village two days after the massacre, he found a place that was “devastated… it looked haunted”.

“Most Muslim residents had either died or were in hospital being treated for injuries, including bullets wounds, or run away.”

The violence in Malyana that summer, he said, was not an isolated incident.

Religious tensions had begun in Meerut weeks earlier after riots broke out on 14 April during a religious procession.

A dozen people, including Hindus and Muslims, were killed and a curfew was imposed, but tensions remained and riots continued to break out sporadically over the next several weeks.

According to official records, 174 people were killed – but unofficial reports say more than 350 people died and property worth billions of rupees was destroyed.

Initially, Mr Rai says, “both sides suffered casualties, but it later became organised violence against Muslims by the police and PAC”.

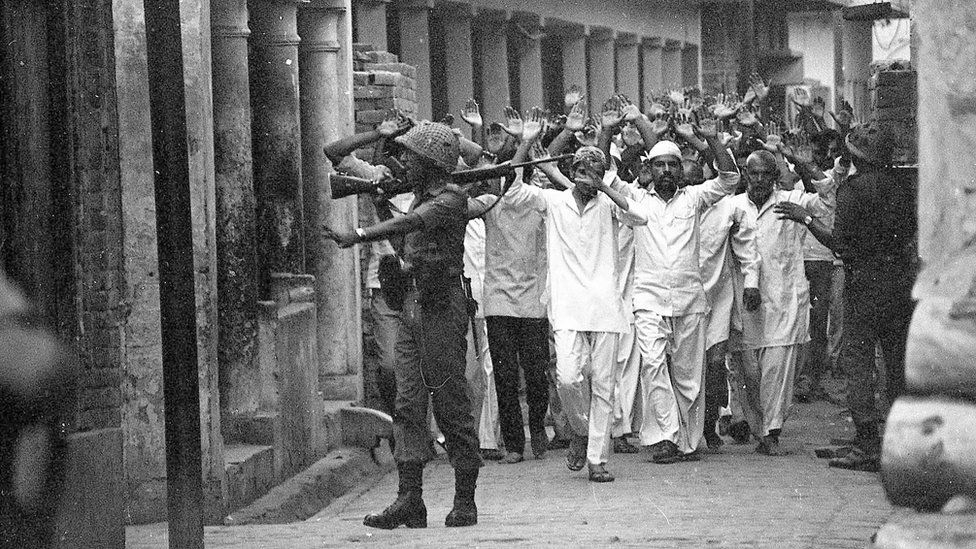

On 22 May, a day before the Malyana massacre, PAC personnel had descended on Hashimpura, a Muslim-dominated locality just 6km away.

They took away 48 men – 42 were shot dead and their bodies were thrown into a river and a canal. Six survived and lived to tell the tale.

Photojournalist Praveen Jain, who was beaten up and told to leave by the police, hid in the bushes and took pictures of Muslim men being assaulted and being marched through the streets.

“When I left, I didn’t know that they were going to be killed,” he told the BBC.

In 2018, the Delhi high court convicted 26 former PAC personnel for abducting and killing Muslims in Hashimpura and sentenced them to life imprisonment.

Sharat Pradhan, a senior journalist in the state capital Lucknow, remembers the PAC being widely criticised for being “communal and anti-Muslim”.

“Most of its personnel came from Hindu backgrounds and – unlike in the army – they were not trained in secularism.”

Mr Pradhan says the fact that justice was delivered in the Hashimpura massacre was mostly due to the efforts of Mr Rai who in 1987 was the superintendent of police in Ghaziabad where the bodies of the murdered men – and a survivor – had turned up.

Mr Ali says he hopes that some day, justice will also be delivered in the Malyana case.

“We are going to challenge the decision in the high court. We won’t give up,” he tells me. “This is a case where justice is not just delayed, it’s also been denied.”

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC: