The Maldives, best known for its pristine beaches, coral reefs and diverse marine life, is the last place you would expect a geopolitical rivalry to play out.

The island nation which consists of about 1,200 coral islands and atolls in the middle of the Indian Ocean will see a run-off poll between President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih and opposition candidate Mohamed Muizzu on 30 September.

But also on the ballot are India and China.

Both countries are trying to strengthen their presence in the strategically located islands which straddle busy east-west shipping lanes.

Maldives’ two presidential contenders, who have been crisscrossing the islands by airplanes and boats to canvass voters, each represent a different Asian power.

Following his surprise win in 2018, Mr Solih from the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) strengthened relations with India with which Malé has strong cultural and financial ties. Mr Muizzu from the Progressive Alliance coalition favours better relations with China.

The Maldives has long been under India’s sphere of influence. Maintaining its presence there gives Delhi the ability to monitor a key part of the Indian Ocean.

China, with its rapidly expanding naval forces, would want access to such a strategically important location – something India wants to prevent. Beijing is also keen to protect its energy supplies from the Gulf which pass through that route.

Both Delhi and Beijing have given the Maldives hundreds of millions of dollars in the form of loans and grants for infrastructure and development projects.

But this election, it seems that China has the edge.

‘India first’

Mr Solih has received just 39% of the votes polled in the first round of elections which were held earlier this month.

One issue that may have hurt the current president’s performance is criticism that his administration has forged close ties with Delhi – called the “India-first” policy – at the expense of China.

But Mr Solih dismisses this argument.

“We do not view it as a zero-sum game where good relations with one country are at the cost of relations with the other,” he told the BBC in an email interview.

One of the reasons the “India first” policy has become unpopular is because of the furore over “gifts” Delhi gave the Maldives – two helicopters received in 2010 and 2013 and a small aircraft in 2020.

Delhi said the craft were to be used for search and rescue missions and medical evacuations.

But in 2021, the Maldivian defence force said about 75 Indian military personnel were based in the country to operate and maintain the Indian aircraft.

Soon after, the opposition began an “India out” campaign which demanded Indian security personnel leave the Maldives.

The opposition argued the presence of these military personnel endangered its national security.

It has now become a key election issue but Mr Solih says these fears are exaggerated.

“There are no militarily active overseas personnel stationed in the Maldives. Indian personnel currently present in the country are under the operational command of the Maldives National Defence Force,” he told the BBC.

Loan and grant diplomacy

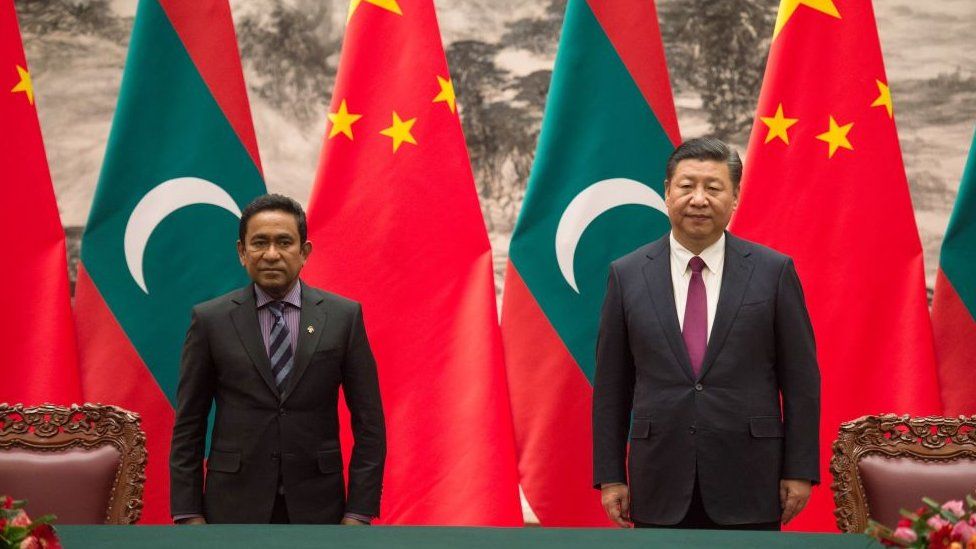

Under Abdulla Yameen, who was president from 2013 to 2018, the Maldives moved closer to China and joined President Xi Jinping’s grand Belt and Road Initiative – to build road, rail and sea links between China and the rest of the world.

When India and Western lenders were not willing to offer loans to Yameen’s administration due to allegations of human rights violations, he turned to Beijing which offered the money without any conditions.

He is currently serving a 11-year prison term for corruption, barring him from contesting this year’s vote. Mr Miuzzu is widely regarded as a proxy for Yameen.

Given Yameen’s tense relationship with Delhi, China is an obvious choice for the opposition to seek support.

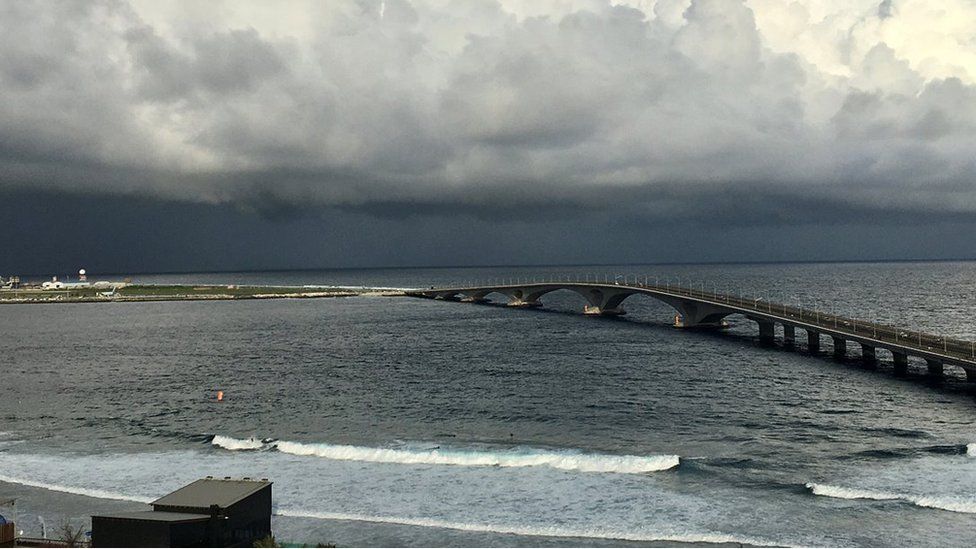

One of the biggest and most visible Chinese funded projects is a 2.1km (1.3 mile) four-lane bridge that connects the capital Malé with the international airport that is situated on a different island. The $200 million (£164m) bridge was inaugurated in 2018 while Yameen was still president.

Though India has also tried to match Chinese investments by offering loans and grants of more than $2bn over the past few years, Delhi’s motives are viewed with suspicion by many in the Maldives. Critics say India indirectly has boots on the ground there.

Another concern is that the Maldives might be affected as tensions between India and China escalate along their Himalayan border,

“There is a much larger sentiment in the Maldives that we should not have any substantive strategic relationship with any country, including India,” says Azim Zahir, a Maldives analyst and a lecturer at the University of Western Australia.

With the run-off due in a few days, Mr Solih is facing a tough battle as he has not managed to rope in key smaller parties to narrow the gap with his rival.

Sensing that the governing MDP has been struggling to counter the “India out” narrative, the opposition alliance has stepped up its offensive.

“We are concerned about the erosion of sovereignty as a result of the current government’s over-dependence on India,” argues Mohamed Hussain Shareef, vice president of the opposition alliance.

He argues that every single project in the country is being carried out through Indian financing and implemented by Indian companies.

But while the “India out” campaign is dominating the campaign, many young Maldivians are worried about rising cost of living, unemployment and climate change.

“We are very concerned about employment opportunities for the youth. Many young people want to migrate even though they are keen to stay back and serve the country,” Ms Fathimath Raaia Shareef, a student at the Maldives National University, told the BBC.

But these domestic issues are likely to take a back seat, as the winner of the election could determine which Asian power wins a vital foothold in the battle for dominance in the region.

-

-

17 September 2020

-